Scars: When They Can No Longer Feel the Pain

AI RAN

Ai is currently a PhD student at the Daniels Faculty, holding degrees in Landscape Architecture and Urban Design. Raised in China’s autonomous prefectures and later having lived in Chengdu, Shanghai, Berlin and Hong Kong, these trajectories have profoundly shaped her interest in mobility and informality embedded in different political and economic structures and cultural contexts. Her practice and research center on urban informality, commodity chains, and bottom-up critical urban practices. Alongside her scholarly pursuits, Ai has gained rich experience through her involvement with non-governmental organizations and visual creation on a part-time basis. Her latest work explores themes such as female labor and scars, and cross-border supply chains. Ai maintains a broad interest in applying interdisciplinary theories and exploring potential urban interventions through experimental design practices, artworks, and actions.

Read the article in PDF form here.

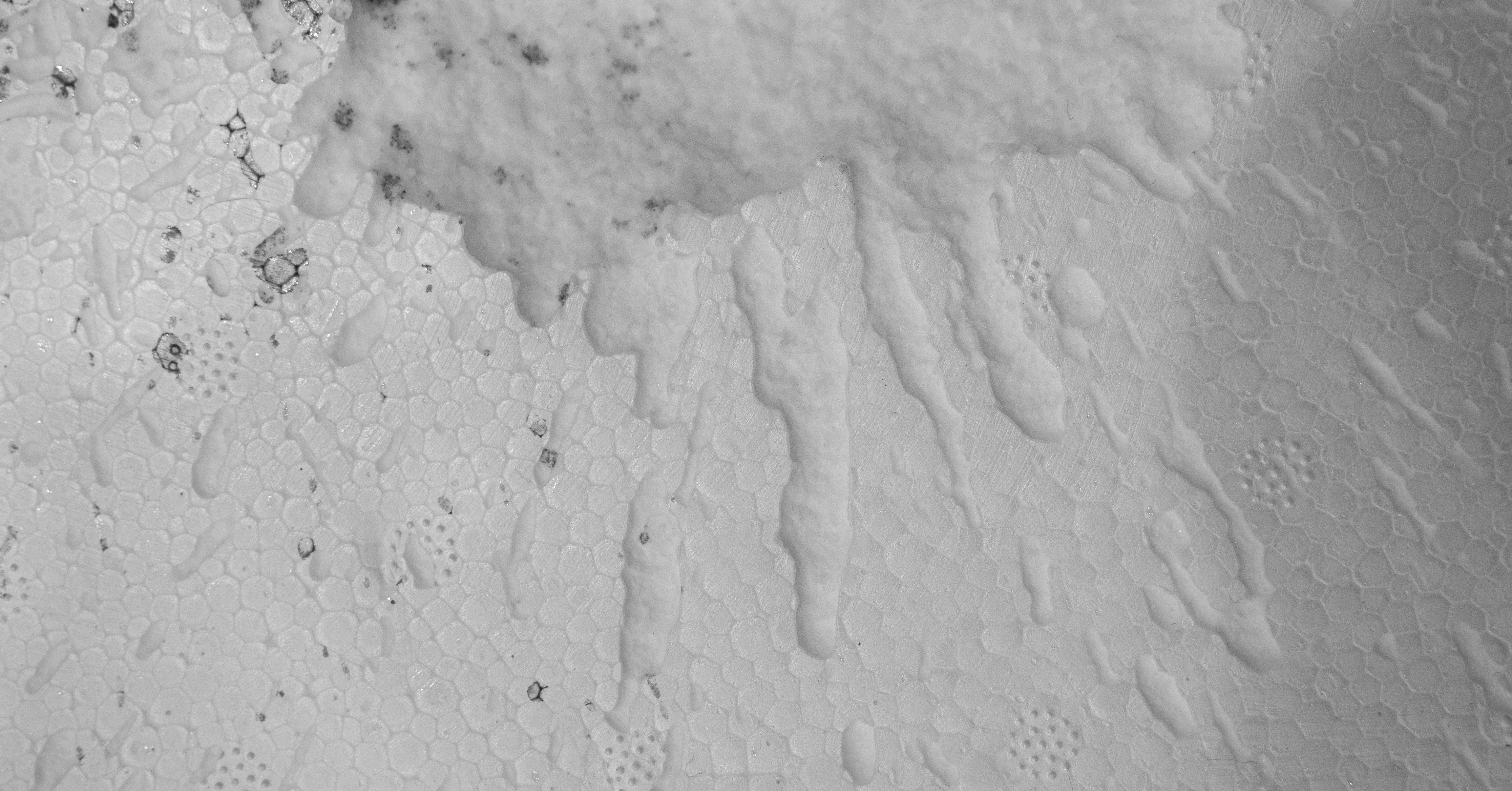

Figure 1. Hot oil spilled on foam board, Toronto, October 2023. Ai Liu.

When it was still fall in Toronto, I started a Research Practicum course. Unexpectedly, “A Ghost in the Throat” written by Doireann Ní Ghríofa was chosen as one of the primary texts: clearly not a conventional choice for a course focused on architectural research.

Following the author’s own narrative, the book pieces together how Ní Ghríofa, as a poetess and in her role as a mother and wife, struggled to carve out moments from her busy, bustling day-to-day life to research and translate the works of another talented but historically overshadowed poetess, Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, whose biographical details have been all but obscured. The narrative of the book is highly fragmented, filled with lists of daily routines, details of the actions of each household chore, as well as the meticulous care with which she weighs each word to decipher the poetry and uncover the context in which Ní Chonaill wrote her verses.

“It is a Tuesday morning, and a security guard in a creased blue uniform is unlocking a door and standing aside with a light-hearted bow, because here I come, with my hair scraped into a rough bun, a milk-stained blouse, a baby in a sling, a toddler in a buggy, a nappy-bag spewing books, and what could only be described as a dangerous light in my eyes…This is how a woman in my situation comes to chase down every translation of Eibhlín Dubh’s words, of which there are many, necessitating many such library visits.”[1]

Ní Ghríofa employs a methodology that departs from what we recognize as the conventional scholarly approach. She lacks verifiable sources, since this poetess did not leave much of a historical record nor did she appear in important epistolary accounts except as a daughter, sister, or wife. Although Ní Ghríofa has been captivated time and again by the passionate words of her great poet, she has had to conceptualize the context of the poems and interpret them through her imagination and her own life experiences with an almost empty source.

Her ‘research’ is guided by experience and perception, detached from the logic of deduction and argumentation favored by rationalism. This departure is not merely a ‘have to’ necessity in the face of the absence of footprints and information but emerges as a courageous rebellion against the dominant research methodologies and intellectual frameworks, especially given the fact that both archives and historical evidence were constructed with gender bias. Ní Ghríofa engages with ‘female text’ to portray the intertwined relationship between a female researcher and her female research subjects, weaving together their shared identities as poetesses, wives, and mothers. These resonate with Judy Chicago’s feminist artwork “The Dinner Party”,[2] which hosted a dinner party to celebrate historically important but overlooked women, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s “Maintenance Art”,[3] a frame-by-frame photographic record of Ukeles’ struggle between her domestic duties and her role as an artist.

“This departure is not merely a ‘have to’ necessity in the face of the absence of footprints and information but emerges as a courageous rebellion against the dominant research methodologies and intellectual frameworks, especially given the fact that both archives and historical evidence were constructed with gender bias.”

Admittedly, ‘the family’ has two sides; it is simultaneously ‘a source of solace and despair’.[4] The family is a place of love and often described as a haven in an alienated society, yet it can also act as a shackle of personal identity and one must leave the family to find one’s own identity. However, in discussing gendered discipline and domestic labor, feminists draw our attention to the very fact that haven and shackles are not equally distributed among family members. From the nineteenth century onwards, discourse on the family has evolved with the rise and fall of the labor movement and with changes in work, providing a foundation for gender emancipatory and feminist critiques.

The ‘Wages for Housework’ campaign[5] was one of its most critical components, critiquing the unpaid, undervalued and taken-for-granted domestic labor, and raising concerns about the crisis of capitalist social reproduction.[6] This call made a theoretical breakthrough from traditional Marxism by arguing that capitalist reproduction depended not only on paid labor but also on unpaid reproductive labor within the family,[7] where the division of labor is distinctly gendered. Radical feminists have argued that the heteronormative nuclear family is essentially a site of violence and authoritarianism beyond its veneer of love and tenderness.

Wages for housework is only the beginning, but its message is clear: from now on they have to pay us because as females we do not guarantee anything any longer. We want to call work when we see it so that eventually we might rediscover love when we see it, and create what will be our sexuality which we have never known. And from the viewpoint of work, we can ask not one wage but many wages, because we have been forced into many jobs at once. We are housemaids, prostitutes, nurses, shrinks; this is the essence of the ‘heroic’ spouse who is celebrated on ‘Mother’s Day’.[8]

After revisiting the historical and theoretical context, it is noteworthy that in addition to presenting the struggles of female identity, Ní Ghríofa’s text and Ukeles’s artwork contribute something exceptional to the table. They offer a methodology that is characterized by rebellion, discursively rejecting the repetitive mainstream, and challenging traditional paradigms. Ukeles brings the cleaning of a dirty diaper into the sacred exhibition space, while Ní Ghríofa mixes milk and details of housework in her translation and research work. This got me to thinking that as women sharing a gender identity but diverging in cultural identities–do we also have a unique methodology to approach such inquiries?

“They offer a methodology that is characterized by rebellion, discursively rejecting the repetitive mainstream, and challenging traditional paradigms.”

After months of these scattered ideas and thoughts lingering in my mind, I discussed them during a chance conversation with a friend who was doing gender studies in the French Literature Department at the time. Despite our different areas of specialization and disciplinary knowledge, our shared interest in such topics sparked further action, and we decided to initiate a female art project to explore our methodologies and languages. My collaborator specializes in writing, while I am more interested in photography or other visual languages. At the start of the project, we had neither found a common creative language nor an entry point for our theme.

Several conversations later, we dug deeper into our respective life experiences and found a point that interested us both. My collaborator mentioned the story of how she used to cook for her family and had scars on her hands from oil burns, which immediately caught my attention. When I was a child, I had a tear mole and it was believed to bring disharmony within the family. It was removed in a moment of panic by my parents’ decision, leaving a subtle scar.

In this way, the topic of scars intersects our life path and naturally became the starting point of our project. In order to further expand this set of concepts, we adopted a collective narrative approach to include a wider range of female life experiences. Through the narrative of different types of female scars in everyday life, we are able to uncover the social relations, gender discipline, and division of labor that lie behind these scars. We began to engage in informal chats and exchanges, as well as formal interviews with women around us. We also searched and read the often-unheard stories in cyberspace. Based on these stories, we further enriched and visualized the content on female scars.

These stories come from the women around us, including our mothers and their mothers before them. We have chosen five representative scars to complete the first set of the project. They come from women of different eras and cultural backgrounds. This set includes small yet recurrent scars caused by years of household chores—burns from cooking with hot oil; fissures and cracks on the palms; pinholes on the fingers from sewing. We also touch on body image anxieties and the appearance of cellulite after weight loss; and a female disease—breast cancer and its corresponding surgical scar— that still receives relatively little attention in many parts of the world.

To present these scars and stories, we decided to use a combination of photography and poetry considering our specialties. The photographs serve as a direct and tangible depiction of the scars, while the poetry narrates the life experiences related with the scars. However, this idea encountered difficulties in its practical implementation. Conducting in-person visits to most of our narrators for on-site photography has been challenging due to geographic distance and the intimate nature of some scars.

Inspired by Mary Kelly’s “Post-Partum Document,”[9] which presents the changing relationship between mother and child through indirect means instead of direct shots of people, we found our alternative. We shifted the focus from directly capturing each scar to photographing everyday objects that are connected with the stories and scenes of these scars. Alongside the scenes and objects, we included another set of photos as complementary to imitate the physical textures of scars by experimenting with different recycled materials.

For instance, when presented with the scar left by splashing oil, we selected kitchenware such as a pot, chopper, chopsticks, spoon, and spatula—items frequently used in the storyteller’s everyday cooking activities. To imitate the scar’s texture, we heated oil and observed its interaction with different materials. Among those, cardboard absorbed the oil; wooden boards remained mostly unchanged; while foam boards performed pleasingly well. Immediately after touching the hot oil, it emitted a sizzling sound and left a thin layer of inconspicuous traces, echoing the aftermath of a burn. Through a series of experiments, we matched materials with scars: used Kraft paper to represent cellulite, and torn corrugated cardboard for the fissured hands.

Our photographs, thus, become abstract representations of scars. They capture the essence of the related life scenes without reducing them to mere visual symbols. The accompanying poems tell the stories of these scars in everyday language, bringing them to a personal depth. As the project develops, it might not become an avant-garde, eye-catching initiative but an authentic, detailed account of the ordinary yet profound realities of everyday life in which its critical and reforming forces are embedded. As Henri Lefebvre puts it:

“Everyday life is not unchangeable; it can decline; therefore, it changes. And moreover, the only genuine, profound human changes are those which cut into this substance and make their mark upon it.”[10]

1. Doireann Ní Ghríofa, A Ghost in the Throat (Windsor, Ontario: Biblioasis, 2021), 23.

2. Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974-1979, Brooklyn Museum, New York.

3. Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Maintenance Art, 1969-ongoing, performance art series, various locations.

4. Michelle Esther O’Brien, To Abolish the Family: The Working-Class Family and Gender Liberation in Capitalist Development, (2020): 362.

5. Kathi Weeks, The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020).

6. Silvia Federici, Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2018).

7. Silvia Federici, Wages Against Housework (Bristol: Falling Wall Press and the Power of Women Collective, 1975), 82.

8. Ghríofa, A Ghost in the Throat, 23.

9. Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1973-1979.

10. Henri Lefebvre, The Critique of Everyday Life, trans. John Moore (London: Verso, 1991), 129.