Stories From The Everyday

DANIEL WONG

I am a third-year M.Arch student at the University of Toronto. I hold a Bachelor of Architectural Science from the British Columbia Institute of Technology (2020) and a Diploma of Architectural Technology from the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (2018). I have developed a wide breadth of professional experience nationwide, working on projects from the scale of family homes to master planning initiatives. Most recently, I have worked at Giannone Petricone Architects. I have also assisted in research projects alongside Michael Piper and Samantha Eby, reHousing the Yellow Belt of Toronto, as well as Ted Kesik and Ross Beardsley Wood in association with the Mass Timber Institute, investigating the historic tall wood towers of Toronto.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

![]()

Figure 1. Acts of Maintenance, Rome, 2023. Daniel Wong.

INTROSPECTION

One drizzling Vancouver morning, I attended my first studio class as a student at the British Columbia Institute of Technology with anxious anticipation. I huddled on a slippery dock surrounded by strangers, and without much introduction, my instructor began to ask the group seemingly vague and esoteric questions while gesturing at the backdrop of Granville island: How does ‘here’ work? Where is the edge? How big is ‘here’?

After some confused responses, we were invited to join him in a circle where I soon found myself humming and stomping my feet in a rhythmic beat as we attentively listened to a Squamish First Nations legend.[1] As the Albertan child of farmers, I found myself feeling awkwardly out of place and wondering what this tale had to do with the study of architecture. As it turned out, this seemingly disconnected exercise proved an invaluable lesson about community, perspective, storytelling, and questioning the borders of architecture and the systems it encompasses.

I am continually reminded of this singular exercise throughout my thesis investigation as this attitude of (seemingly vague and esoteric) questioning has set the foundation for how I conduct research. Throughout this process of introspection, I have realized that there is no clear direction or answer, no boundary or edge. We can only reflect on the vast experiences and influences that have guided the process.

FORMULATION

The thesis, “{In}Visible Maintenance,” examines the maintenance, cleaning, and repair of buildings in order to counter obsolescence. Slowly, the thesis has transformed into a polemical response to the current conditions of how we care for buildings. Throughout this process, I have questioned the universally practiced acts of everyday maintenance that often go unnoticed in the background of the new. I recall two occasions during my undergraduate experience that were formative in broadening my perspective on maintenance, cleaning, and repair.

The first of these took place that day on the dock. The Vancouver House by BIG had just been completed: a fifty-six-story residential tower distinguished by its wedge-shaped base that expands as it rises into a slender rectangle. My peers and I were captivated by the building, yet, my professor remarked that in a mere thirty years, the building’s sleek, shiny facade would lose its allure. With its sculpted form, the building would be less accessible for proper maintenance and cleaning. Eventually, this building would experience age and decay over time, prompting extensive refurbishment if not properly maintained. This instilled a new awareness of the roles that cleaning and maintenance promote in extending the lifespan and the durability of a building.

The second pivotal moment occurred after visiting Strawberry Vale Elementary by Patkau Architects. The caretakers remarked about the challenges of cleaning the building. Yet, I was encouraged to reconsider that one can either look at cleaning as an inconvenience or as a way to appreciate the uniqueness of the building. If we value something, we place our attention on its care, and through maintenance and cleaning, we extend its value. Ultimately, as long as the users value the building, this care is warranted.

As the thesis semester loomed closer, the challenge of selecting a topic became daunting. At the time, these two offhand conversations left an impression but quickly faded into the periphery of my consciousness. These conversations, however, gained renewed significance during my first year at the University of Toronto when I enrolled in the elective “Normal Architecture” taught by Hans Ibelings. In this seminar class, we tried to unpack the everydayness of architecture, and the margins between the ordinary and the generic. Unknowingly, many of the themes, topics, and theories discussed in that class would weave their way into my perspective and understanding of architecture.

This research did not emerge as a singular work but as a culmination of multiple influences, instructors, and mentors with whom I had the pleasure of working. My ideas, perspectives, and rationales have often originated from mundane, overlooked conversations that unexpectedly gain significance, much like the process of maintenance, cleaning and repair. These interactions prompted me to reconsider my position and values in ways I never knew existed.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 2. Acts of Maintenance, Rome, 2023. Daniel Wong.

SIGNIFICATION

As my initially peripheral interest in maintenance, cleaning, and repair progressed, I developed a perverse distaste for many of architecture’s more extractive processes. I started to see that the world is often fixated on what is new: nothing lasts nor endures, trends come and quickly fall into obsolescence. We find ourselves attracted to the aesthetics of the smooth.[2] The smooth embodies societal values of beauty: reflected in our glass, steel, and concrete buildings. Byung-Chul Han argues in his philosophical essay “Saving Beauty” that the new or the smooth embodies today’s society of positivity, writing that “what is smooth does not endure, nor does it offer any resistance, it is looking for the like and the smooth deletes and forms of negativity and deletes the against”.[3] Many of the facades of today’s architecture are plastered with the idea of the smooth, the absence of resistance through soft, smooth transitions that resist interpretation, deciphering, or reflection. We pursue objects that offer immediate satisfaction, producing more and more to fuel a system that satisfies our tendencies of overconsumption and boredom.[4] The smooth and the new become a source of misguided pleasure. In contrast, decay or the ugly becomes a response to an acute crisis; a state of emergency for self-preservation. Maintenance, cleaning, and repair aim to heal; they counteract the idea of the smooth.

Our capitalist mode of production is approaching a climate crisis: global droughts, torrential rains, heat deaths, and floods are becoming far too familiar. This is not aided by construction trends, which dictate that once a building is obsolete, the action is to demolish and build new. This irresponsible practice is a driving force of our unsustainable mode of production and overconsumption. Yet, we all know that there are more responsible ways to design, but we continue to practice architecture that “rewards creation not maintenance, novelty not repair.”[5] Every day objects are replaced, discarded, neglected, and left to decay. It is only when things become inoperable do they come into focus—they become the object of attention. What was once background becomes foreground.

Perhaps a designer’s job is not solely about creating new for the sake of newness. Perhaps it should involve recognizing the enormous beauty and wealth of things that already exist around us. Is this a point where we re-adjust the role of the designer from a self-indulgent author to a more humble professional, whose awareness re-acknowledges the natural goodness in the dilapidated, the strange, or the ordinary?[6] The architecture of the everyday is not summarized by the heroic achievements of construction, ribbon-cutting, or crude wealth plastered over the facades, but by the mundane, ordinary, and everyday acts of care. Often rendered invisible, the banal and minor acts of maintenance, cleaning, and repair are worth celebrating.[7] Ultimately—in conceptualizing the ideas of cleaning, maintenance, and repair—this thesis underwent various gestational periods, shaped by numerous readings, endless writing, and countless open discussions with my advisor, Carol Moukehiber. Ultimately, the stories, events and close everyday observations have led to my understanding that cleaning is continuous, maintenance is temporary, and repair is infinite. These processes have facilitated the emergence of a holistic understanding and definition and played a pivotal role in shaping and refining these definitions.

Cleaning is an act of love; it is an allegory for living. However, cleaning is never the pleasurable idealization of an architect or for the user’s consumption.[8] As a result, societal culture undervalues it. Cleaning has no glamor or novelty, yet the act is inherently intimate; it centers on the individual and the domestic, and it concerns itself with a building’s specific part at a particular moment. Cleaning, unlike maintenance or repair, temporarily resets the quality of an object. The ambition of this manual upkeep is to extend the object’s cycle of use.

Maintenance is work; it is labor but skilled labor. Maintenance involves routine, organization, and planning; it is a public act, not a private one.[9] Maintenance extends the building cycle of use, as the order is alternatively regained and, over time, lost. Unlike cleaning, the reproductive labor of maintenance requires the formal planning of skilled laborers. It represents the investment in preserving a building to be in good working order. Our entropic world is constantly breaking down; maintenance highlights the decay, and it is our chief means of seeing and understanding the world.

[10]

Maintenance is learning; it teaches us why things break down, and it offers us the structure for experimentation and innovation.

Repair takes the rough, ugly, injured fragments of the everyday and attempts to mend them. However, repair is only sometimes necessarily concerned with improvements; like maintenance, they do not always have to be exact restorations. Repair and maintenance can be a vital source of variation, improvisation and innovation by reinterpreting conservation methods and applying them creatively. Yet, repairs do not detract from the experience of an object or building; they are intrinsic, inseparable parts of the piece’s timeline. In the end, a botched job still fulfills the role of repair. If so, the object can continue functioning, albeit at a lower level.[11]

![]()

![]()

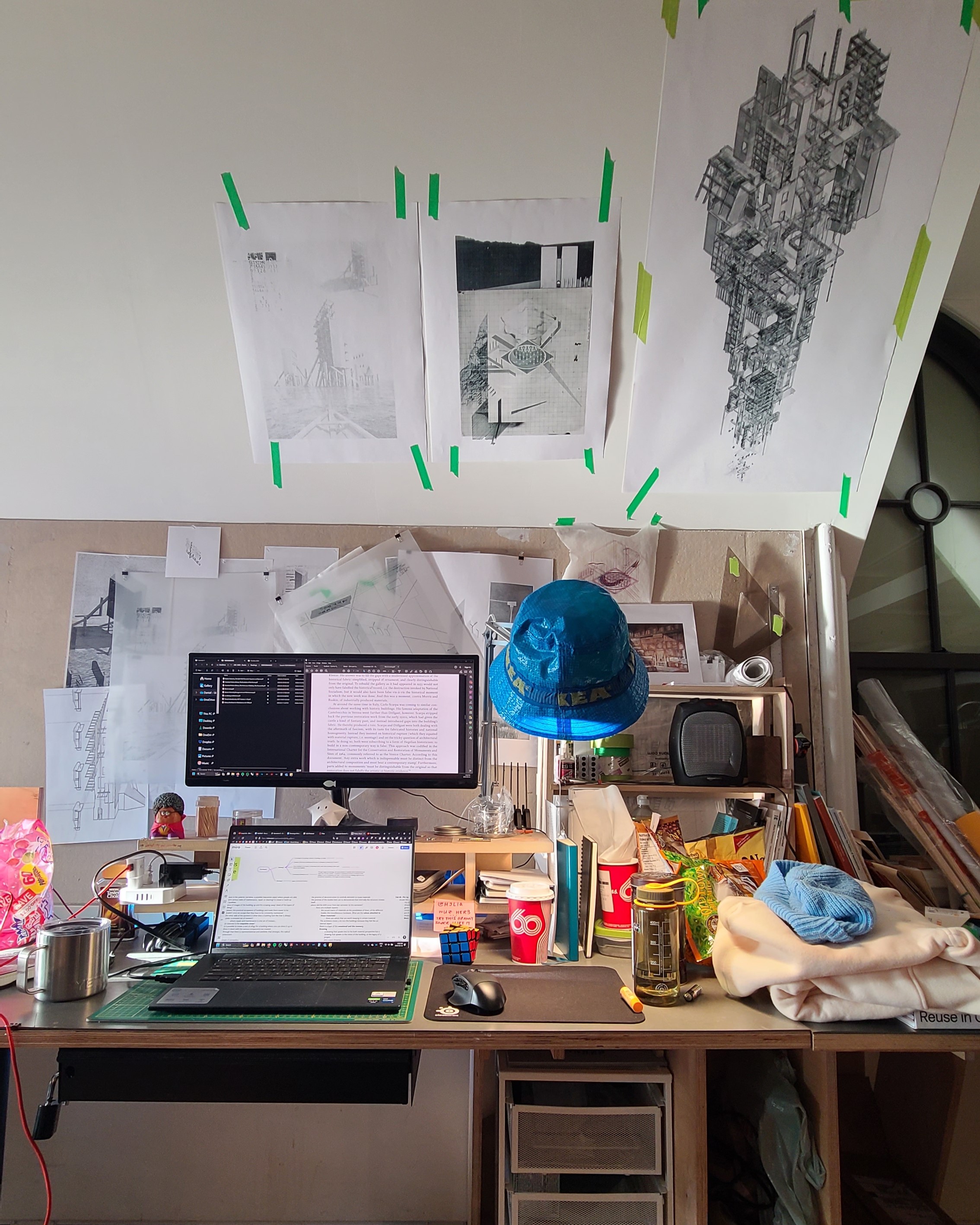

Figure 3. Studio Workflow, Toronto, 2023. Photo by Sahar Hakimpour.

IDEATION {A STUDIO INTERLUDE}

I attribute much of my workflow to studio culture, which has profoundly impacted how I operate and negotiate my work. Reflecting on my formative years in Vancouver, I realize that the studio has been a laboratory for experimentation–a testing ground. There is no better way to learn and push the limits than to experience failure and restart, acknowledging the feeling of uncertainty and daring to commit without knowing the future. The studio becomes a place for myself and my peers to test, develop, propose, and synthesize materials from a diverse catalogue of sources. In many ways, the studio becomes a second home, and my peers become my new family. It is a place of collaboration, intellectual exchanges, and caffeine-fueled production. The studio was where I learned firsthand about the process of making, and in doing so, it instilled an operative self-resilience.

The studio in Toronto is no different—it has once again become a second home. The studio becomes a set of operations: a place for work, a place of creativity, a place of refuge, a place of discourse, and a place of experimentation. The studio is not only a physical sanctuary but also a psychological sanctuary; it becomes a guardian of stories, identity, and memories. A place with those attributes, one could imagine that some wonderful things could emerge from it.

OBSERVATION

The process of creating the drawings that have formed my thesis began from the observations of the everyday. In October 2023, I travelled to Rome to study how the city’s various periods have accommodated and facilitated transitions and transformations over time. My focus, however, diverged towards the everyday upkeep necessary to maintain Rome’s picturesque charm.

Before the crowds of tourists descend onto the streets from their continental breakfast, one will notice the street sweepers in the early morning cleaning the refuse of the previous day. They will notice the custodians diligently tending behind restricted areas; the groundskeeper tidying up after trimming the garden trees. They will ritualistically go to the same early morning cafe and watch the waiter who has been following the same routine for years, tidying up the empty coffee cups and wiping away the spills.

Cleaning, in its essence, is inherently humanist; it establishes a balance between nature and the built environment. Poetically speaking, the humble custodian, gardener, or groundskeeper is often the one who intimately understands the durability of a material. They are the mediators between architects, buildings, and their users. Rome, for me, was a city that was constantly rebuilding itself from the ruins, adding, patching, removing, sweeping, scrubbing, revising, and maintaining itself.

The lessons from Rome highlighted themes of tending, age, value, time, beauty, ruins and rebuilding. I took the many observations from Rome—teachings from my overlooked conversations, my interest in the everyday—and started to develop the thesis. Ultimately I found myself questioning what is possible if we take decay, breakdown, and disorder as our starting points in architectural durability. I started to dwell on and rethink the possibility of a different reality by pushing the situational absurdity to its limits. This ultimately led to one thought experiment of a 1000-year-old building.

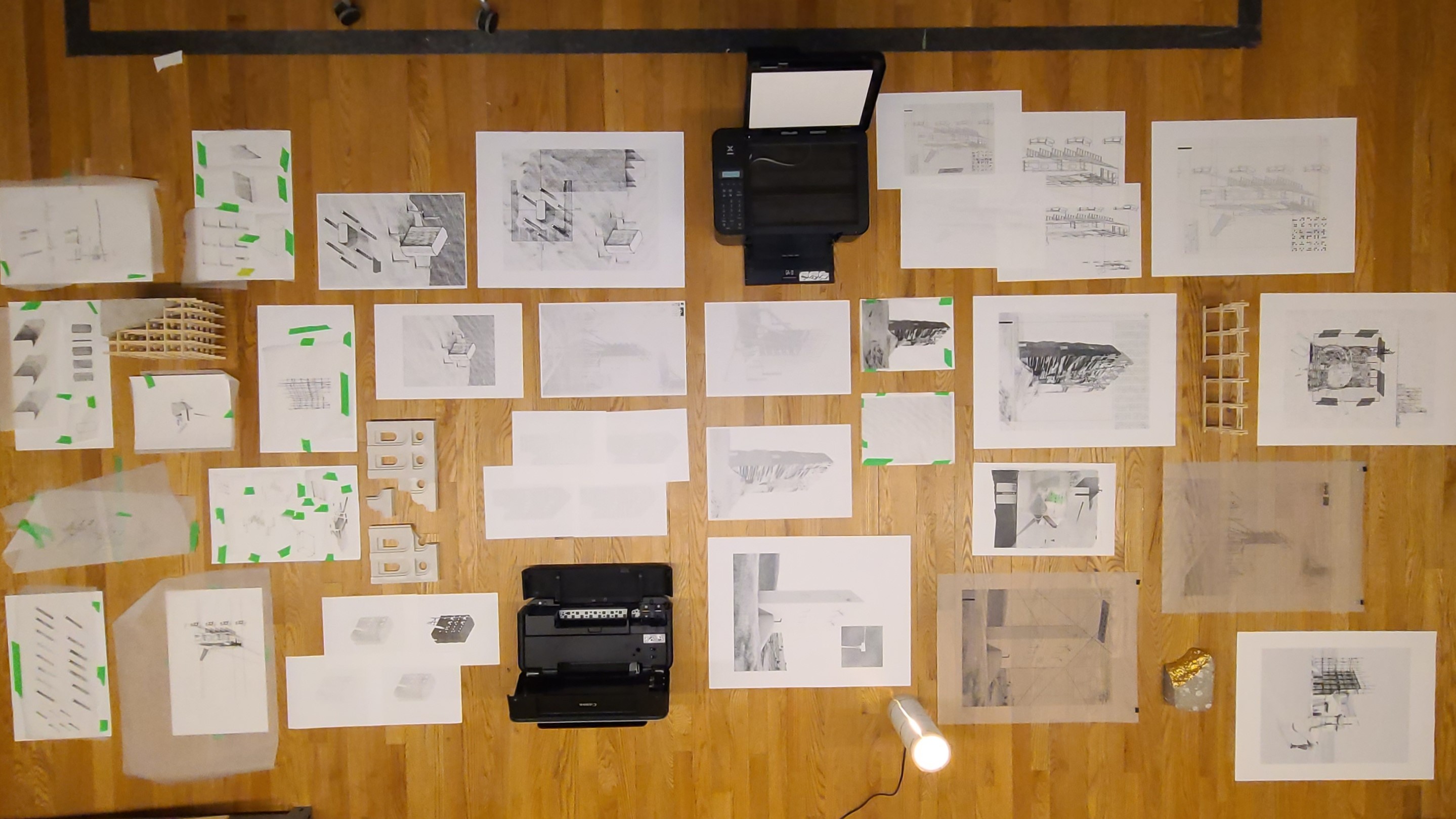

![]()

Figure 4. Representation as Storytelling, 2023. Daniel Wong.

REPRESENTATION

Three evolving narratives envision the concept of a millennium-old building enduring the ongoing impact of climate change. The onslaught of nature from rising sea levels, temperature fluctuations, and drought threatens the existence of humanity and the buildings we inhabit. Yet, through maintenance and repair, evidence of habitation persists—albeit in the ruins of their former self. The drawings attempt to reframe the idea of cleaning, maintenance, and repair, highlighting that each process of dilapidation creates new ‘wastes’ and new opportunities.

Each drawing in the series adopts different representation styles, through which it becomes evident that time gradually transforms the drawings, mirroring the changes that occur in a building after maintenance and repair. The drawings undergo erosion, become cryptic, shift, and evolve, akin to acts of repair where both the building and drawings take on new meanings.

The art style of xerography served as an early inspiration, where 2D scans were assembled, and the recursive overlapping of scans created a compositional collage. This concept is expanded by integrating digital, analogue, and parametric means. Each drawing follows a chronological sequence, yet each evolves in its naturalistic way, attempting to convey the passage of time. The knowledge and means of repair and maintenance ultimately change throughout the years, influencing the organic evolution of the drawings and the built environment they represent.

Drawing is used to tell a story, a tool to craft a narrative that redefines the concept of building material degradation as circular opportunities for reuse and repurposing. To expand on this narrative of repair, I utilized broken, discarded, and obsolete printers to develop the drawings. After repairing these discarded printers, each one presented unique and captivating qualities in their prints. One misprinted, creating beautiful moments of misalignment, while another, with a broken inkhead, produced a feeble dot matrix print. Repairing these printers proved invaluable in the evolution of the drawings and the overall thesis, demonstrating that the often broken, decrepit, and discarded possess untapped potential and new opportunities. It underscores the importance of recognizing value and not hastily passing judgment on objects simply because they have broken down or gone out of style.

The process of crafting these drawings also aims to reflect the circular nature of repair. Each drawing undergoes a series of steps, starting with being 3D modelled, plotted, sketched on, scanned, digitally modified, and reprinted. These recursive processes of repetitive overprints and scans bring about a transformation in the drawing each time, encouraging contemplation on the acts of maintenance and repair. An interplay between analog, digital, and parametric elements is carefully stitched and patched together to develop a multifaceted theme of mending and adaptation through a palimpsest of details. These drawings invite us to reflect on technological progression and the shifting roles of craft, permanence, waste, value, and age.

{In}Visible Maintenance offers an alternative vision somewhere between the speculative, the surreal, and the plausible; a resistance to our valuation of existing buildings. Drawing is used as a method of unravelling the everyday maintenance, cleaning, and repair of buildings, highlighting its palimpsest history of time, age and care work.

I am a third-year M.Arch student at the University of Toronto. I hold a Bachelor of Architectural Science from the British Columbia Institute of Technology (2020) and a Diploma of Architectural Technology from the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (2018). I have developed a wide breadth of professional experience nationwide, working on projects from the scale of family homes to master planning initiatives. Most recently, I have worked at Giannone Petricone Architects. I have also assisted in research projects alongside Michael Piper and Samantha Eby, reHousing the Yellow Belt of Toronto, as well as Ted Kesik and Ross Beardsley Wood in association with the Mass Timber Institute, investigating the historic tall wood towers of Toronto.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Acts of Maintenance, Rome, 2023. Daniel Wong.

INTROSPECTION

One drizzling Vancouver morning, I attended my first studio class as a student at the British Columbia Institute of Technology with anxious anticipation. I huddled on a slippery dock surrounded by strangers, and without much introduction, my instructor began to ask the group seemingly vague and esoteric questions while gesturing at the backdrop of Granville island: How does ‘here’ work? Where is the edge? How big is ‘here’?

After some confused responses, we were invited to join him in a circle where I soon found myself humming and stomping my feet in a rhythmic beat as we attentively listened to a Squamish First Nations legend.[1] As the Albertan child of farmers, I found myself feeling awkwardly out of place and wondering what this tale had to do with the study of architecture. As it turned out, this seemingly disconnected exercise proved an invaluable lesson about community, perspective, storytelling, and questioning the borders of architecture and the systems it encompasses.

I am continually reminded of this singular exercise throughout my thesis investigation as this attitude of (seemingly vague and esoteric) questioning has set the foundation for how I conduct research. Throughout this process of introspection, I have realized that there is no clear direction or answer, no boundary or edge. We can only reflect on the vast experiences and influences that have guided the process.

FORMULATION

The thesis, “{In}Visible Maintenance,” examines the maintenance, cleaning, and repair of buildings in order to counter obsolescence. Slowly, the thesis has transformed into a polemical response to the current conditions of how we care for buildings. Throughout this process, I have questioned the universally practiced acts of everyday maintenance that often go unnoticed in the background of the new. I recall two occasions during my undergraduate experience that were formative in broadening my perspective on maintenance, cleaning, and repair.

The first of these took place that day on the dock. The Vancouver House by BIG had just been completed: a fifty-six-story residential tower distinguished by its wedge-shaped base that expands as it rises into a slender rectangle. My peers and I were captivated by the building, yet, my professor remarked that in a mere thirty years, the building’s sleek, shiny facade would lose its allure. With its sculpted form, the building would be less accessible for proper maintenance and cleaning. Eventually, this building would experience age and decay over time, prompting extensive refurbishment if not properly maintained. This instilled a new awareness of the roles that cleaning and maintenance promote in extending the lifespan and the durability of a building.

The second pivotal moment occurred after visiting Strawberry Vale Elementary by Patkau Architects. The caretakers remarked about the challenges of cleaning the building. Yet, I was encouraged to reconsider that one can either look at cleaning as an inconvenience or as a way to appreciate the uniqueness of the building. If we value something, we place our attention on its care, and through maintenance and cleaning, we extend its value. Ultimately, as long as the users value the building, this care is warranted.

As the thesis semester loomed closer, the challenge of selecting a topic became daunting. At the time, these two offhand conversations left an impression but quickly faded into the periphery of my consciousness. These conversations, however, gained renewed significance during my first year at the University of Toronto when I enrolled in the elective “Normal Architecture” taught by Hans Ibelings. In this seminar class, we tried to unpack the everydayness of architecture, and the margins between the ordinary and the generic. Unknowingly, many of the themes, topics, and theories discussed in that class would weave their way into my perspective and understanding of architecture.

This research did not emerge as a singular work but as a culmination of multiple influences, instructors, and mentors with whom I had the pleasure of working. My ideas, perspectives, and rationales have often originated from mundane, overlooked conversations that unexpectedly gain significance, much like the process of maintenance, cleaning and repair. These interactions prompted me to reconsider my position and values in ways I never knew existed.

Figure 2. Acts of Maintenance, Rome, 2023. Daniel Wong.

SIGNIFICATION

As my initially peripheral interest in maintenance, cleaning, and repair progressed, I developed a perverse distaste for many of architecture’s more extractive processes. I started to see that the world is often fixated on what is new: nothing lasts nor endures, trends come and quickly fall into obsolescence. We find ourselves attracted to the aesthetics of the smooth.[2] The smooth embodies societal values of beauty: reflected in our glass, steel, and concrete buildings. Byung-Chul Han argues in his philosophical essay “Saving Beauty” that the new or the smooth embodies today’s society of positivity, writing that “what is smooth does not endure, nor does it offer any resistance, it is looking for the like and the smooth deletes and forms of negativity and deletes the against”.[3] Many of the facades of today’s architecture are plastered with the idea of the smooth, the absence of resistance through soft, smooth transitions that resist interpretation, deciphering, or reflection. We pursue objects that offer immediate satisfaction, producing more and more to fuel a system that satisfies our tendencies of overconsumption and boredom.[4] The smooth and the new become a source of misguided pleasure. In contrast, decay or the ugly becomes a response to an acute crisis; a state of emergency for self-preservation. Maintenance, cleaning, and repair aim to heal; they counteract the idea of the smooth.

“Perhaps a designer’s job is not solely about creating new for the sake of newness. Perhaps it should involve recognizing the enormous beauty and wealth of things that already exist around us.”

Our capitalist mode of production is approaching a climate crisis: global droughts, torrential rains, heat deaths, and floods are becoming far too familiar. This is not aided by construction trends, which dictate that once a building is obsolete, the action is to demolish and build new. This irresponsible practice is a driving force of our unsustainable mode of production and overconsumption. Yet, we all know that there are more responsible ways to design, but we continue to practice architecture that “rewards creation not maintenance, novelty not repair.”[5] Every day objects are replaced, discarded, neglected, and left to decay. It is only when things become inoperable do they come into focus—they become the object of attention. What was once background becomes foreground.

Perhaps a designer’s job is not solely about creating new for the sake of newness. Perhaps it should involve recognizing the enormous beauty and wealth of things that already exist around us. Is this a point where we re-adjust the role of the designer from a self-indulgent author to a more humble professional, whose awareness re-acknowledges the natural goodness in the dilapidated, the strange, or the ordinary?[6] The architecture of the everyday is not summarized by the heroic achievements of construction, ribbon-cutting, or crude wealth plastered over the facades, but by the mundane, ordinary, and everyday acts of care. Often rendered invisible, the banal and minor acts of maintenance, cleaning, and repair are worth celebrating.[7] Ultimately—in conceptualizing the ideas of cleaning, maintenance, and repair—this thesis underwent various gestational periods, shaped by numerous readings, endless writing, and countless open discussions with my advisor, Carol Moukehiber. Ultimately, the stories, events and close everyday observations have led to my understanding that cleaning is continuous, maintenance is temporary, and repair is infinite. These processes have facilitated the emergence of a holistic understanding and definition and played a pivotal role in shaping and refining these definitions.

Cleaning is an act of love; it is an allegory for living. However, cleaning is never the pleasurable idealization of an architect or for the user’s consumption.[8] As a result, societal culture undervalues it. Cleaning has no glamor or novelty, yet the act is inherently intimate; it centers on the individual and the domestic, and it concerns itself with a building’s specific part at a particular moment. Cleaning, unlike maintenance or repair, temporarily resets the quality of an object. The ambition of this manual upkeep is to extend the object’s cycle of use.

Maintenance is work; it is labor but skilled labor. Maintenance involves routine, organization, and planning; it is a public act, not a private one.[9] Maintenance extends the building cycle of use, as the order is alternatively regained and, over time, lost. Unlike cleaning, the reproductive labor of maintenance requires the formal planning of skilled laborers. It represents the investment in preserving a building to be in good working order. Our entropic world is constantly breaking down; maintenance highlights the decay, and it is our chief means of seeing and understanding the world.

[10]

Maintenance is learning; it teaches us why things break down, and it offers us the structure for experimentation and innovation.

Repair takes the rough, ugly, injured fragments of the everyday and attempts to mend them. However, repair is only sometimes necessarily concerned with improvements; like maintenance, they do not always have to be exact restorations. Repair and maintenance can be a vital source of variation, improvisation and innovation by reinterpreting conservation methods and applying them creatively. Yet, repairs do not detract from the experience of an object or building; they are intrinsic, inseparable parts of the piece’s timeline. In the end, a botched job still fulfills the role of repair. If so, the object can continue functioning, albeit at a lower level.[11]

Figure 3. Studio Workflow, Toronto, 2023. Photo by Sahar Hakimpour.

IDEATION {A STUDIO INTERLUDE}

I attribute much of my workflow to studio culture, which has profoundly impacted how I operate and negotiate my work. Reflecting on my formative years in Vancouver, I realize that the studio has been a laboratory for experimentation–a testing ground. There is no better way to learn and push the limits than to experience failure and restart, acknowledging the feeling of uncertainty and daring to commit without knowing the future. The studio becomes a place for myself and my peers to test, develop, propose, and synthesize materials from a diverse catalogue of sources. In many ways, the studio becomes a second home, and my peers become my new family. It is a place of collaboration, intellectual exchanges, and caffeine-fueled production. The studio was where I learned firsthand about the process of making, and in doing so, it instilled an operative self-resilience.

The studio in Toronto is no different—it has once again become a second home. The studio becomes a set of operations: a place for work, a place of creativity, a place of refuge, a place of discourse, and a place of experimentation. The studio is not only a physical sanctuary but also a psychological sanctuary; it becomes a guardian of stories, identity, and memories. A place with those attributes, one could imagine that some wonderful things could emerge from it.

OBSERVATION

The process of creating the drawings that have formed my thesis began from the observations of the everyday. In October 2023, I travelled to Rome to study how the city’s various periods have accommodated and facilitated transitions and transformations over time. My focus, however, diverged towards the everyday upkeep necessary to maintain Rome’s picturesque charm.

“Cleaning, in its essence, is inherently humanist; it establishes a balance between nature and the built environment.”

Before the crowds of tourists descend onto the streets from their continental breakfast, one will notice the street sweepers in the early morning cleaning the refuse of the previous day. They will notice the custodians diligently tending behind restricted areas; the groundskeeper tidying up after trimming the garden trees. They will ritualistically go to the same early morning cafe and watch the waiter who has been following the same routine for years, tidying up the empty coffee cups and wiping away the spills.

Cleaning, in its essence, is inherently humanist; it establishes a balance between nature and the built environment. Poetically speaking, the humble custodian, gardener, or groundskeeper is often the one who intimately understands the durability of a material. They are the mediators between architects, buildings, and their users. Rome, for me, was a city that was constantly rebuilding itself from the ruins, adding, patching, removing, sweeping, scrubbing, revising, and maintaining itself.

The lessons from Rome highlighted themes of tending, age, value, time, beauty, ruins and rebuilding. I took the many observations from Rome—teachings from my overlooked conversations, my interest in the everyday—and started to develop the thesis. Ultimately I found myself questioning what is possible if we take decay, breakdown, and disorder as our starting points in architectural durability. I started to dwell on and rethink the possibility of a different reality by pushing the situational absurdity to its limits. This ultimately led to one thought experiment of a 1000-year-old building.

Figure 4. Representation as Storytelling, 2023. Daniel Wong.

REPRESENTATION

Three evolving narratives envision the concept of a millennium-old building enduring the ongoing impact of climate change. The onslaught of nature from rising sea levels, temperature fluctuations, and drought threatens the existence of humanity and the buildings we inhabit. Yet, through maintenance and repair, evidence of habitation persists—albeit in the ruins of their former self. The drawings attempt to reframe the idea of cleaning, maintenance, and repair, highlighting that each process of dilapidation creates new ‘wastes’ and new opportunities.

Each drawing in the series adopts different representation styles, through which it becomes evident that time gradually transforms the drawings, mirroring the changes that occur in a building after maintenance and repair. The drawings undergo erosion, become cryptic, shift, and evolve, akin to acts of repair where both the building and drawings take on new meanings.

The art style of xerography served as an early inspiration, where 2D scans were assembled, and the recursive overlapping of scans created a compositional collage. This concept is expanded by integrating digital, analogue, and parametric means. Each drawing follows a chronological sequence, yet each evolves in its naturalistic way, attempting to convey the passage of time. The knowledge and means of repair and maintenance ultimately change throughout the years, influencing the organic evolution of the drawings and the built environment they represent.

Drawing is used to tell a story, a tool to craft a narrative that redefines the concept of building material degradation as circular opportunities for reuse and repurposing. To expand on this narrative of repair, I utilized broken, discarded, and obsolete printers to develop the drawings. After repairing these discarded printers, each one presented unique and captivating qualities in their prints. One misprinted, creating beautiful moments of misalignment, while another, with a broken inkhead, produced a feeble dot matrix print. Repairing these printers proved invaluable in the evolution of the drawings and the overall thesis, demonstrating that the often broken, decrepit, and discarded possess untapped potential and new opportunities. It underscores the importance of recognizing value and not hastily passing judgment on objects simply because they have broken down or gone out of style.

“Drawing is used to tell a story, a tool to craft a narrative that redefines the concept of building material degradation as circular opportunities for reuse and repurposing.”

The process of crafting these drawings also aims to reflect the circular nature of repair. Each drawing undergoes a series of steps, starting with being 3D modelled, plotted, sketched on, scanned, digitally modified, and reprinted. These recursive processes of repetitive overprints and scans bring about a transformation in the drawing each time, encouraging contemplation on the acts of maintenance and repair. An interplay between analog, digital, and parametric elements is carefully stitched and patched together to develop a multifaceted theme of mending and adaptation through a palimpsest of details. These drawings invite us to reflect on technological progression and the shifting roles of craft, permanence, waste, value, and age.

{In}Visible Maintenance offers an alternative vision somewhere between the speculative, the surreal, and the plausible; a resistance to our valuation of existing buildings. Drawing is used as a method of unravelling the everyday maintenance, cleaning, and repair of buildings, highlighting its palimpsest history of time, age and care work.

- The Legends of the Two Sisters, originally told by Squamish Chief Joe Capilano, tells us of how the iconic peaks came to stand over what has become Vancouver. The legend tells of two warring nations who were brought together by the Great Chief’s daughters for a Potlatch, creating a lasting peace among the Coast Salish People. After their passing, the two sisters were lifted up to the mountains and immortalized into the twin peaks, where they could forever keep watch over their descendants and ensure the peace was kept.

-

Byung-Chul Han, Saving Beauty, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018), 1.

-

Han, Saving Beauty, 1.

- Ibid.

-

Daniel A. Barber, “Drawing the Line,” Places Journal, January (2024): 1.

-

Naoto Fukasawa and Jasper Morrison, Super Normal: Sensations of the Ordinary, (Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2007), 99.

-

Helene Frichot “Mottos for maintenance as care work” in Open for Maintenance, ed. Nikolaus Kuhnert, and Anh-Linh Ngo, (Arch+, 252. Spector Books), 23-25. Books), 23-25.

- Hilary Sample, Maintenance Architecture (MIT Press, 2018), 106.

-

Sample, Maintenance Architecture, 7.

- Stephen Graham and Nigel Thrift, “Out of Order,” Theory, Culture & Society 24, no. 3 (May 2007): 5.

- Graham, and Thrift, “Out of Order,” 6.