Before the UAE There Was the Dragon Blood Tree

FARWA MUMTAZ

Farwa Mumtaz is a distinguished alumna of the University of Toronto, holding a Masters in Architecture as well as a Bachelor of Arts in Architectural Design and Architectural History, Theory, and Criticism. Farwa’s interests evidently extend beyond traditional architecture, through her groundbreaking thesis which delves into the intersection between architecture, geopolitics, and game design. Passionate about empowering and building communities, she specializes in creating socially meaningful spaces. Her

dedication to inclusivity through design since 2016 and fostering digital spaces during the pandemic for the Muslim community at large earned her the IDEAS Impact Fellowship Award.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

Figure 1. Map of Geographic Region, 2023, Farwa Mumtaz. Socotra Archipelago, Yemen and UAE, the two main parties involved in this case study are highlighted among the global network of submarine cables. The Yemeni Socotra Archipelago (with the largest of its islands named Socotra) sits at a strategic location at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden, which is a portion of the Suez waterway connecting Europe to Asia.

Colonial-imperial expansion is an ongoing reality that can be traced not only through books, accounts, or images, but also through seemingly innocuous and banal spatial practices that appear time and time again in the built environment. As architects and designers, we should always have an awareness that we are complicit in this process, that architectural typologies are planned and situated in specific locations, at specific times, by the influence of geopolitical forces. At what moment in our practice are we in too deep? Do we have a choice to stop, reverse, or somehow change the process going forward? Do we remain complicit, or can we begin to mobilize?

Banal Architecture and Tactile Narratives: Before the UAE, There was the Dragon Blood Tree is my M.Arch thesis project at the University of Toronto under the tutelage of Professor Lukas Pauer, the founder of investigative think tank Vertical Geopolitics Lab, completed over two semesters. It explores the Yemeni Socotra Archipelago, known for its endemic flora and fauna, as a designated UNESCO Natural World Heritage site located in a strategic position at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden. Taking advantage of civil war on the mainland and consecutive cyclones, the UAE has incrementally gained control of Socotra through the construction of seemingly innocuous hospitals, schools, base transceiver stations, and other built projects under the guise of ‘humanitarian aid and disaster relief’.

To exemplify the insidious technique that the UAE has employed on the island as means of occupation, it was important for me to also use a similarly unassuming medium of output. Aside from having a personal interest in the intersection between architecture and gaming, I know games to objectively be an effective and immersive method to communicate complex topics in a way that is tactile, social, spatial, and engaging to a wide audience. This is because games can represent and embody real-life scenarios, and are often utilized as a counter-technique when discussing geopolitical scenarios. Historically, this technique has been applied by kriegsspiel, the German word for “wargame”, wherein games are used by military organizations for their realistic decision-making capabilities towards training and research.

The culmination of my thesis research was then a performative exhibition parallelly exposing the imperial-colonial playbook of the UAE on Socotra Island through the similarly innocuous activity of playing a tabletop game

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY OVERVIEW

Holistically, the project comprised of two overarching parts— Research and Output. Ultimately, both my Research and Output phases aimed to catalyze the Critical Moment in which the audience realizes that they are complicit in larger, occasionally obscured, processes. The research itself was also divided into two areas: Case Study Investigation and Narrative Implementation; the former of which is recounted in this issue.

Much of the methodology I engaged with during the Case Study Investigation was embedded within the meticulous research framework of the course, which aimed to bridge media and discourse analysis with spatial and material reconstruction. Possible case studies were distributed across four techniques that are often employed in the projection of power. These techniques are categorized by Pauer as scenographic, extraterritorial, geodetic, and filtrational. I completed two preliminary research cycles on two separate case studies before settling on one. I focused on media and discourse analysis in relation to the scenographic sovereignty dispute between Morocco and Western Sahara for the first cycle and the second cycle focused on spatial and material reconstruction of the geodetic occupation by the UAE on the Yemeni Socotra Archipelago.

![]()

Figure 2. Relational diagram of select endemic terrestrial species of Socotra Island. with the exception of the Egyptian vulture, a significant migratory species characteristic of the island. 2023, Farwa Mumtaz.

To briefly delve into the preliminary research cycle for the latter a little, the method to identify probable construction projects by the UAE towards spatial and material construction began by utilizing GIS mapping, Google Maps investigation, and photo matching. I then created hypothetical 3D models of each construction project based on aerial imagery and photographs.

After completing both preliminary cycles, I gave myself only a week to settle the dilemma on which of the two I would move forward with and trusted my choice until the end. Because of the extremely short timeframe to decide, I based my decision more so on the prospective output and aesthetics of the final project over pure interest. That being said, it was thrilling to choose the option that had the allure of mystery–and Socotra, often dubbed as the ‘most alien place on Earth’, left a lot of question marks in my notebook.

To fill in the blanks still left in the case study, I went back to conduct extensive media and discourse analysis on the ongoing geopolitical situation by evaluating varying perspectives on the subject. Combining textual and visual information, Soqotri, Emirati, conservation, and international perspectives were analysed towards developing a timeline of events, taxonomy of projects, and stakeholders. This material was then readied for the second area of research, Narrative Implementation, which transitioned the project into my chosen Output medium of a game.

INVESTIGATION, DATA COLLECTION, AND ORGANIZATION

To begin investigating, it was important to dissect the research prompt I had been given into its parts: Geodetic Practice, Emirati Arabian Suqutra Archipelago Etisalat Base Transceiver Stations. ‘What do these words mean and how do they relate to each other?’ I wondered. This question was answered soon enough, by learning more about the complex geopolitical situation at hand and by immersing myself in this mesmerizing region of the world that should be protected from the negative prospects of an invasive built environment.

After dissecting the prompt, the rest of the research was guided by follow-up questions, data collection, reconstruction, and analysis, which can be broken down into the following tasks.

TASK 1A: LEARNING THE GEOPOLITICAL SITUATION

Gain an overview of the geopolitical situation, parties involved, and the built object in question. Where is Socotra and why is it important? How did the UAE gain access to the archipelago? How are telecommunication towers being used on Socotra?

In real time, the immediate objective was mapping and constructing 3D models, so I prioritized gaining an overview rather than thorough understanding of the case using an array of traditional and non-traditional sources of information. On one hand, traditional sources, such as research papers and documents by UNESCO, were instrumental in gaining insight on the workings of the archipelago itself, or scientific knowledge like indigenous Soqotri culture and its endemic biodiversity. On the other hand, non-traditional sources from news articles, YouTube videos, social media posts, to blogs, proved more useful in documenting recent facts on the ground. The latter would form the basis for analyzing the claim that the UAE was testing boundaries on the archipelago through its built projects.

![]()

Figure 3. Spatial diagram visualizing the diversity in landscape on Socotra Island juxtaposed with activity by the UAE (United Arab Emirates) such as the construction of telecom towers, 2023. Farwa Mumtaz.

Gaining primary information and insight from the Soqotri perspective was daunting since I do not speak Arabic. However, it was the most useful and involved a cycle of translating Tweets, videos, and articles from local news channels so that new keywords or locations could be obtained for further investigation. For example, a video news report by the Yemeni outlet Belqees TV described a newly constructed telecom tower constructed by the UAE in the Socotri capital city, Hadiboh.[1] After having a friend translate the video content and name its location, I was able to find it on Google Maps. Unlike other sources which were outdated or focused on providing an overview of the situation rather than specifics, the local report revealed the appearance and location of these telecom towers, allowing me to complete Task 2.

TASK 1B: ORGANIZING KEY MOMENTS INTO A TIMELINE

Create a Timeline of Events and Built Projects. When were the telecom towers first erected and where are they located? What other moments in time are pivotal in the case study?

Diving head-first into task 1A, there were many occasions where I was told to stop researching because I kept falling down irrelevant rabbit holes. Simply grouping information, placing sticky notes, arrows, and other annotation tools in Miro was not enough to declutter everything I was consuming. To tackle this issue, I realized that building a concise timeline would be beneficial in not only keeping track of all my findings but also weeding out the most important and relevant aspects so that the situation was conveyed as a coherent story.

While surveying sources, I collected as many images, dates, and key events as I could find. The timeline functions as a form of traceable, organized evidence in the research process. Evidently, it revealed a pattern in the types of buildings being constructed: although the UAE nobly gained access to Socotra when cyclones hit in 2015 through aid operations and projects, later activity relates less and less to the original premise.

Superficially, the UAE has invested more than $110 million in providing humanitarian aid and disaster relief (HADR). While projects for medical care, water, and energy justified humanitarian aid in earlier years, recent projects showcase larger, permanent infrastructural and cultural facilities that feed into a greater network. For example, direct flights from Abu Dhabi have operated since 2018, where you can buy Emirati SIM cards before even stepping foot on the island.[2] This creates a seamless transition on arrival to Socotra, as if you never left the UAE at all.

Finding that telecom towers were not the only built projects that UAE had implemented on Socotra was a major breakthrough in this research cycle. As I kept investigating the situation at hand, the scope expanded from one tower to six and from one typology to fourteen. During the preliminary research cycle I only found seven typologies. I didn’t know at the time, but the claws that the UAE had sunk into Socotra were wedged quite deep. Fourteen typologies were catalogued by the end of the entire thesis project.

TASK 2A: SPATIAL ANALYSIS AND MAPPING

Map Socotra and the UAE across various geographic scales and overlay Built Projects. How can the location of these objects be spatially analyzed? Are they part of a larger network? How might Etisalat be involved?

A series of maps were created at the building scale, district scale, city scale, assumed tower radius scale, island scale, geographic region scale, and continental scale. Much of the geographic information and spatial data I found relating to Socotra Archipelago was open-source and used in conjunction with QGIS. Unfortunately, there was very little relevant data besides basic map layers like roads, topography, hydrology, tree cover, medical centres, and some 2D building footprints in major cities. Most spatial data in my research was collected manually in the grueling process of cross-referencing locations and pictures mentioned in online news articles, blogs, social media, etc. and then floating around in satellite mode on Google Maps until I found the built project in question. I utilized the ‘My Maps’ feature to add custom points and export the KML file directly onto the base map layers I collated on QGIS. While uncovering the built projects as part of larger networks, I followed a similar process in investigating relevant locations and projects beyond the island— for instance, mapping telecom towers associated with Etisalat and its subsidiaries worldwide.

A key finding was noticing that most of the telecom towers constructed were located along the coast of the island, with a hypothetical range of 45km. This range would make it possible to obtain signals along the ocean and monitor ships that pass through the island’s vicinity, increasing the UAE’s presence and power in the region. As we know, the archipelago is located at a chokepoint at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden, one of the world’s busiest shipping and global submarine cable networks connecting Europe, East Africa, and Asia via the Suez Canal.

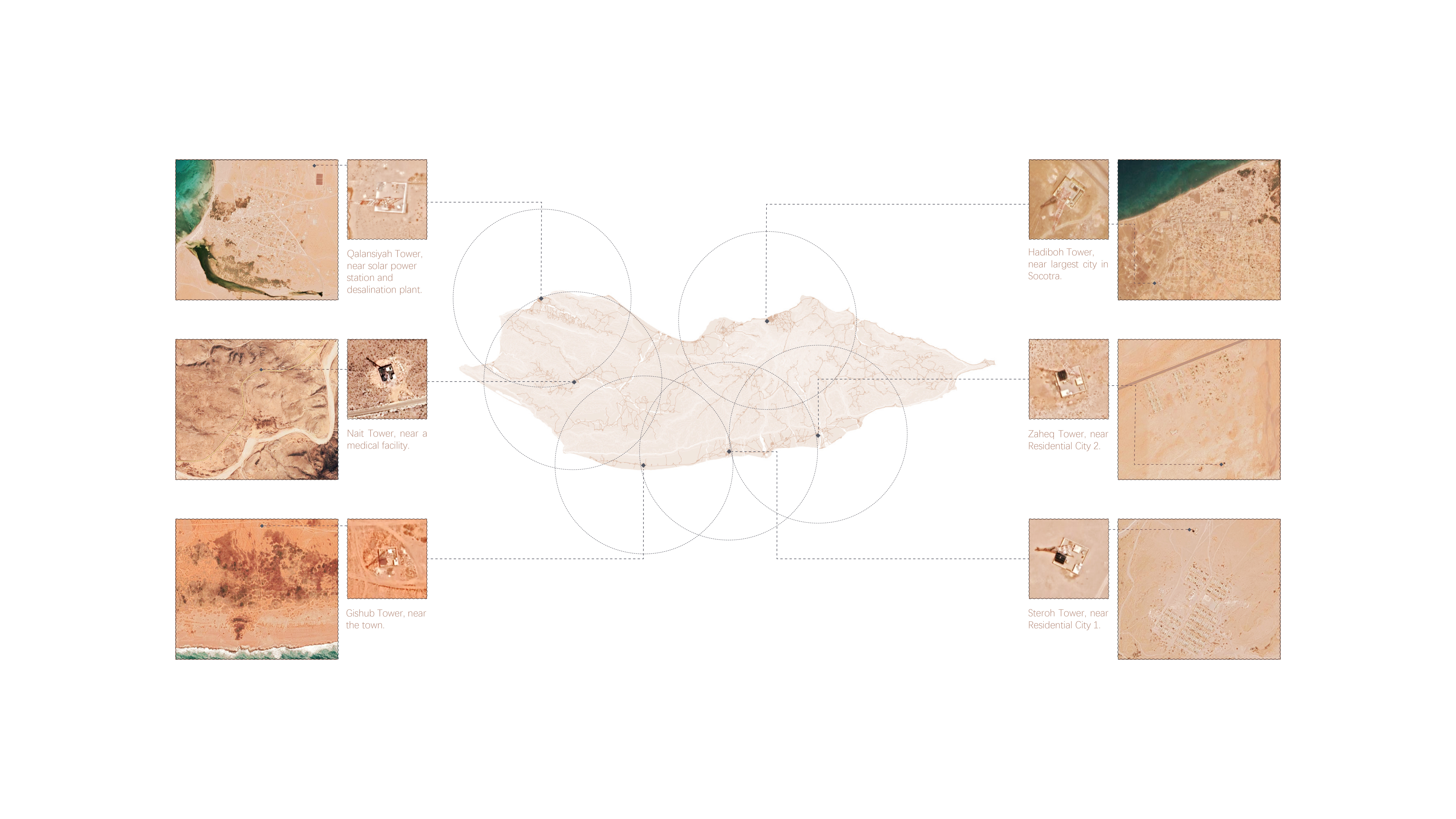

![]()

Figure 4. A collection of telecom towers that have been identified via aerial imagery, often appearing alongside other projects. The radius is assumed to be 45 km as an average for towers installed in rural areas, 2023. Farwa Mumtaz.

TASK 2B: 3D MODELLING AND HYPOTHETICAL RECONSTRUCTION

What do these towers and other projects look like? How are they being used? How much space do they occupy? Are there other projects in their vicinity?

Much of the 3D modelling was done in Rhino based on images found within Task 1 as well as estimated measurements from the aerial footage in Task 2A. As such, they are hypothetical reconstructions. Many projects are concentrated in major existing cities and some are part of new ‘residential cities’ situated along the scenic Southern coast of the island. Some of these projects have a large footprint, such as a new seaport, water infrastructure, and the Rabdan sports stadium. Others are small; like community wells or airport security scanners. Some of the models were easy to model because of how heavily they are documented in reports by the UAE, while others had me trying to decipher blurry screenshots from Google Maps. Regardless, having a roster of 3D models was key to exploring possible components during Output, many of which were 3D printed.

![]()

Figure 5. Overview of projects implemented by the UAE on Socotra Island and corresponding locations on a map. Earlier projects for medical care, water, and energy are justified for humanitarian aid. However, recent projects showcase larger, permanent fixtures and cultural interventions that feed into a greater network. Note: models are hypothetical reconstructions, 2023. Farwa Mumtaz.

TASK 3: FILLING IN THE GAPS

After utilizing a heavily spatial and object-oriented methodology, I went back to techniques explored during the first preliminary research cycle on the Morocco-Western Sahara study to fill in the gaps remaining in the Case Study Investigation phase of the thesis project.

This involved classifying visual and textual information into categories that serve as precise introductory perspectives and context for the thesis project. These categories are: geographic location, biodiversity [and heritage status], current situation, political context, humanitarian aid and disaster relief, Emirati perspective, Yemeni perspective, conservation perspective, other [international] perspectives, and object insights for all fourteen typologies.

An important aspect of this method was to pay attention to the specific language, types of visuals, and ideas that were put forward by each party involved, exemplified by media companies, headings published, and imagery. I went back and forth to edit, refine, and apply this context for all outputs of the project.

Completing this task was crucial for the next phases – Narrative Implementation and Output. I had most, if not all, the pieces I needed to start testing effective communication of the subject matter in the form of a game for its capability in representing and embodying real-life scenarios as a counter-hegemonic medium. Combining textual, visual, and spatial information, helped to formulate the narrative and mechanics of a game effectively. This ensured that my audience became fully immersed in the geopolitical situation while forming a personal connection with the archipelago through interaction. As such, the moment of realization that they had been complicit in a larger agenda (the Critical Moment) would be an unforgettable experience.

REFLECTION

In hindsight, I can see how important it was that as a researcher I kept trusting the process even when the prospects of a breakthrough seemed bleak. The countless hours hovering over satellite maps were always trumped by the exhilarating feeling of finding what was meant to be uncovered. I personally found myself at a Critical Moment when I realized that there were more than telecom towers at play. As such, the next phase of the project sought to spark this moment in others. But how could it be done by using the same language as the occupier? In this case, occupational language utilized a seemingly innocuous entry onto the island such as providing humanitarian aid and disaster relief, a grey area when compared to blatant and more violent methods of colonial occupation.

At the start of the course, I was quite sure that the Output medium I wanted to explore was a game. However, the case study and site itself was yet to be decided. This thesis could have gone in many directions, just as a game can have multiple endings, side quests, storylines, and characters to discover. The challenge was that I didn’t know how to play this one in the beginning. Nonetheless, I took on the challenge and was rewarded in the end. The next phases, Narrative Implementation and Output, I begin to demonstrate how this thesis functions as a spatial, social, and tactile tool that exposes the imperial-colonial playbook of the UAE, prompting discussion, reactions, and possible long-term plans for Socotra amongst players and beyond.

1. Taiz Time. October 10, 2022. https://twitter.com/TaizTime/status/1579441615311196160

2. Trips with Rosie. December 22, 2023. https://tripswithrosie.com/socotra-island-hidden-paradise-in-the-world/

Farwa Mumtaz is a distinguished alumna of the University of Toronto, holding a Masters in Architecture as well as a Bachelor of Arts in Architectural Design and Architectural History, Theory, and Criticism. Farwa’s interests evidently extend beyond traditional architecture, through her groundbreaking thesis which delves into the intersection between architecture, geopolitics, and game design. Passionate about empowering and building communities, she specializes in creating socially meaningful spaces. Her

dedication to inclusivity through design since 2016 and fostering digital spaces during the pandemic for the Muslim community at large earned her the IDEAS Impact Fellowship Award.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Map of Geographic Region, 2023, Farwa Mumtaz. Socotra Archipelago, Yemen and UAE, the two main parties involved in this case study are highlighted among the global network of submarine cables. The Yemeni Socotra Archipelago (with the largest of its islands named Socotra) sits at a strategic location at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden, which is a portion of the Suez waterway connecting Europe to Asia.

Colonial-imperial expansion is an ongoing reality that can be traced not only through books, accounts, or images, but also through seemingly innocuous and banal spatial practices that appear time and time again in the built environment. As architects and designers, we should always have an awareness that we are complicit in this process, that architectural typologies are planned and situated in specific locations, at specific times, by the influence of geopolitical forces. At what moment in our practice are we in too deep? Do we have a choice to stop, reverse, or somehow change the process going forward? Do we remain complicit, or can we begin to mobilize?

Banal Architecture and Tactile Narratives: Before the UAE, There was the Dragon Blood Tree is my M.Arch thesis project at the University of Toronto under the tutelage of Professor Lukas Pauer, the founder of investigative think tank Vertical Geopolitics Lab, completed over two semesters. It explores the Yemeni Socotra Archipelago, known for its endemic flora and fauna, as a designated UNESCO Natural World Heritage site located in a strategic position at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden. Taking advantage of civil war on the mainland and consecutive cyclones, the UAE has incrementally gained control of Socotra through the construction of seemingly innocuous hospitals, schools, base transceiver stations, and other built projects under the guise of ‘humanitarian aid and disaster relief’.

To exemplify the insidious technique that the UAE has employed on the island as means of occupation, it was important for me to also use a similarly unassuming medium of output. Aside from having a personal interest in the intersection between architecture and gaming, I know games to objectively be an effective and immersive method to communicate complex topics in a way that is tactile, social, spatial, and engaging to a wide audience. This is because games can represent and embody real-life scenarios, and are often utilized as a counter-technique when discussing geopolitical scenarios. Historically, this technique has been applied by kriegsspiel, the German word for “wargame”, wherein games are used by military organizations for their realistic decision-making capabilities towards training and research.

The culmination of my thesis research was then a performative exhibition parallelly exposing the imperial-colonial playbook of the UAE on Socotra Island through the similarly innocuous activity of playing a tabletop game

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY OVERVIEW

Holistically, the project comprised of two overarching parts— Research and Output. Ultimately, both my Research and Output phases aimed to catalyze the Critical Moment in which the audience realizes that they are complicit in larger, occasionally obscured, processes. The research itself was also divided into two areas: Case Study Investigation and Narrative Implementation; the former of which is recounted in this issue.

Much of the methodology I engaged with during the Case Study Investigation was embedded within the meticulous research framework of the course, which aimed to bridge media and discourse analysis with spatial and material reconstruction. Possible case studies were distributed across four techniques that are often employed in the projection of power. These techniques are categorized by Pauer as scenographic, extraterritorial, geodetic, and filtrational. I completed two preliminary research cycles on two separate case studies before settling on one. I focused on media and discourse analysis in relation to the scenographic sovereignty dispute between Morocco and Western Sahara for the first cycle and the second cycle focused on spatial and material reconstruction of the geodetic occupation by the UAE on the Yemeni Socotra Archipelago.

Figure 2. Relational diagram of select endemic terrestrial species of Socotra Island. with the exception of the Egyptian vulture, a significant migratory species characteristic of the island. 2023, Farwa Mumtaz.

To briefly delve into the preliminary research cycle for the latter a little, the method to identify probable construction projects by the UAE towards spatial and material construction began by utilizing GIS mapping, Google Maps investigation, and photo matching. I then created hypothetical 3D models of each construction project based on aerial imagery and photographs.

After completing both preliminary cycles, I gave myself only a week to settle the dilemma on which of the two I would move forward with and trusted my choice until the end. Because of the extremely short timeframe to decide, I based my decision more so on the prospective output and aesthetics of the final project over pure interest. That being said, it was thrilling to choose the option that had the allure of mystery–and Socotra, often dubbed as the ‘most alien place on Earth’, left a lot of question marks in my notebook.

To fill in the blanks still left in the case study, I went back to conduct extensive media and discourse analysis on the ongoing geopolitical situation by evaluating varying perspectives on the subject. Combining textual and visual information, Soqotri, Emirati, conservation, and international perspectives were analysed towards developing a timeline of events, taxonomy of projects, and stakeholders. This material was then readied for the second area of research, Narrative Implementation, which transitioned the project into my chosen Output medium of a game.

INVESTIGATION, DATA COLLECTION, AND ORGANIZATION

To begin investigating, it was important to dissect the research prompt I had been given into its parts: Geodetic Practice, Emirati Arabian Suqutra Archipelago Etisalat Base Transceiver Stations. ‘What do these words mean and how do they relate to each other?’ I wondered. This question was answered soon enough, by learning more about the complex geopolitical situation at hand and by immersing myself in this mesmerizing region of the world that should be protected from the negative prospects of an invasive built environment.

-

Geodetic Practice— When a nation-state uses built objects for instant administration, integration, and synchronization of places by dissolving distance, it may choose to use a range of varieties, whether internet or telecommunication facilities from base transceiver stations, to clock towers.

-

Emirati Arabian—The United Arab Emirates, located in the Arabian Peninsula

-

Suqutra Archipelago— a Yemeni archipelago between the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Aden, named after its largest island; spelling varies but is written commonly as Socotra

-

Etisalat— Emirates Telecommunications Group Company PJSC doing business as ‘Etisalat by E&’, a company/provider of base transceiver stations based in the UAE

-

Base Transceiver Stations— in this situation, telecommunication towers

After dissecting the prompt, the rest of the research was guided by follow-up questions, data collection, reconstruction, and analysis, which can be broken down into the following tasks.

TASK 1A: LEARNING THE GEOPOLITICAL SITUATION

Gain an overview of the geopolitical situation, parties involved, and the built object in question. Where is Socotra and why is it important? How did the UAE gain access to the archipelago? How are telecommunication towers being used on Socotra?

In real time, the immediate objective was mapping and constructing 3D models, so I prioritized gaining an overview rather than thorough understanding of the case using an array of traditional and non-traditional sources of information. On one hand, traditional sources, such as research papers and documents by UNESCO, were instrumental in gaining insight on the workings of the archipelago itself, or scientific knowledge like indigenous Soqotri culture and its endemic biodiversity. On the other hand, non-traditional sources from news articles, YouTube videos, social media posts, to blogs, proved more useful in documenting recent facts on the ground. The latter would form the basis for analyzing the claim that the UAE was testing boundaries on the archipelago through its built projects.

Figure 3. Spatial diagram visualizing the diversity in landscape on Socotra Island juxtaposed with activity by the UAE (United Arab Emirates) such as the construction of telecom towers, 2023. Farwa Mumtaz.

Gaining primary information and insight from the Soqotri perspective was daunting since I do not speak Arabic. However, it was the most useful and involved a cycle of translating Tweets, videos, and articles from local news channels so that new keywords or locations could be obtained for further investigation. For example, a video news report by the Yemeni outlet Belqees TV described a newly constructed telecom tower constructed by the UAE in the Socotri capital city, Hadiboh.[1] After having a friend translate the video content and name its location, I was able to find it on Google Maps. Unlike other sources which were outdated or focused on providing an overview of the situation rather than specifics, the local report revealed the appearance and location of these telecom towers, allowing me to complete Task 2.

TASK 1B: ORGANIZING KEY MOMENTS INTO A TIMELINE

Create a Timeline of Events and Built Projects. When were the telecom towers first erected and where are they located? What other moments in time are pivotal in the case study?

Diving head-first into task 1A, there were many occasions where I was told to stop researching because I kept falling down irrelevant rabbit holes. Simply grouping information, placing sticky notes, arrows, and other annotation tools in Miro was not enough to declutter everything I was consuming. To tackle this issue, I realized that building a concise timeline would be beneficial in not only keeping track of all my findings but also weeding out the most important and relevant aspects so that the situation was conveyed as a coherent story.

While surveying sources, I collected as many images, dates, and key events as I could find. The timeline functions as a form of traceable, organized evidence in the research process. Evidently, it revealed a pattern in the types of buildings being constructed: although the UAE nobly gained access to Socotra when cyclones hit in 2015 through aid operations and projects, later activity relates less and less to the original premise.

Superficially, the UAE has invested more than $110 million in providing humanitarian aid and disaster relief (HADR). While projects for medical care, water, and energy justified humanitarian aid in earlier years, recent projects showcase larger, permanent infrastructural and cultural facilities that feed into a greater network. For example, direct flights from Abu Dhabi have operated since 2018, where you can buy Emirati SIM cards before even stepping foot on the island.[2] This creates a seamless transition on arrival to Socotra, as if you never left the UAE at all.

Finding that telecom towers were not the only built projects that UAE had implemented on Socotra was a major breakthrough in this research cycle. As I kept investigating the situation at hand, the scope expanded from one tower to six and from one typology to fourteen. During the preliminary research cycle I only found seven typologies. I didn’t know at the time, but the claws that the UAE had sunk into Socotra were wedged quite deep. Fourteen typologies were catalogued by the end of the entire thesis project.

TASK 2A: SPATIAL ANALYSIS AND MAPPING

Map Socotra and the UAE across various geographic scales and overlay Built Projects. How can the location of these objects be spatially analyzed? Are they part of a larger network? How might Etisalat be involved?

A series of maps were created at the building scale, district scale, city scale, assumed tower radius scale, island scale, geographic region scale, and continental scale. Much of the geographic information and spatial data I found relating to Socotra Archipelago was open-source and used in conjunction with QGIS. Unfortunately, there was very little relevant data besides basic map layers like roads, topography, hydrology, tree cover, medical centres, and some 2D building footprints in major cities. Most spatial data in my research was collected manually in the grueling process of cross-referencing locations and pictures mentioned in online news articles, blogs, social media, etc. and then floating around in satellite mode on Google Maps until I found the built project in question. I utilized the ‘My Maps’ feature to add custom points and export the KML file directly onto the base map layers I collated on QGIS. While uncovering the built projects as part of larger networks, I followed a similar process in investigating relevant locations and projects beyond the island— for instance, mapping telecom towers associated with Etisalat and its subsidiaries worldwide.

A key finding was noticing that most of the telecom towers constructed were located along the coast of the island, with a hypothetical range of 45km. This range would make it possible to obtain signals along the ocean and monitor ships that pass through the island’s vicinity, increasing the UAE’s presence and power in the region. As we know, the archipelago is located at a chokepoint at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden, one of the world’s busiest shipping and global submarine cable networks connecting Europe, East Africa, and Asia via the Suez Canal.

Figure 4. A collection of telecom towers that have been identified via aerial imagery, often appearing alongside other projects. The radius is assumed to be 45 km as an average for towers installed in rural areas, 2023. Farwa Mumtaz.

TASK 2B: 3D MODELLING AND HYPOTHETICAL RECONSTRUCTION

What do these towers and other projects look like? How are they being used? How much space do they occupy? Are there other projects in their vicinity?

Much of the 3D modelling was done in Rhino based on images found within Task 1 as well as estimated measurements from the aerial footage in Task 2A. As such, they are hypothetical reconstructions. Many projects are concentrated in major existing cities and some are part of new ‘residential cities’ situated along the scenic Southern coast of the island. Some of these projects have a large footprint, such as a new seaport, water infrastructure, and the Rabdan sports stadium. Others are small; like community wells or airport security scanners. Some of the models were easy to model because of how heavily they are documented in reports by the UAE, while others had me trying to decipher blurry screenshots from Google Maps. Regardless, having a roster of 3D models was key to exploring possible components during Output, many of which were 3D printed.

Figure 5. Overview of projects implemented by the UAE on Socotra Island and corresponding locations on a map. Earlier projects for medical care, water, and energy are justified for humanitarian aid. However, recent projects showcase larger, permanent fixtures and cultural interventions that feed into a greater network. Note: models are hypothetical reconstructions, 2023. Farwa Mumtaz.

TASK 3: FILLING IN THE GAPS

After utilizing a heavily spatial and object-oriented methodology, I went back to techniques explored during the first preliminary research cycle on the Morocco-Western Sahara study to fill in the gaps remaining in the Case Study Investigation phase of the thesis project.

This involved classifying visual and textual information into categories that serve as precise introductory perspectives and context for the thesis project. These categories are: geographic location, biodiversity [and heritage status], current situation, political context, humanitarian aid and disaster relief, Emirati perspective, Yemeni perspective, conservation perspective, other [international] perspectives, and object insights for all fourteen typologies.

An important aspect of this method was to pay attention to the specific language, types of visuals, and ideas that were put forward by each party involved, exemplified by media companies, headings published, and imagery. I went back and forth to edit, refine, and apply this context for all outputs of the project.

Completing this task was crucial for the next phases – Narrative Implementation and Output. I had most, if not all, the pieces I needed to start testing effective communication of the subject matter in the form of a game for its capability in representing and embodying real-life scenarios as a counter-hegemonic medium. Combining textual, visual, and spatial information, helped to formulate the narrative and mechanics of a game effectively. This ensured that my audience became fully immersed in the geopolitical situation while forming a personal connection with the archipelago through interaction. As such, the moment of realization that they had been complicit in a larger agenda (the Critical Moment) would be an unforgettable experience.

REFLECTION

In hindsight, I can see how important it was that as a researcher I kept trusting the process even when the prospects of a breakthrough seemed bleak. The countless hours hovering over satellite maps were always trumped by the exhilarating feeling of finding what was meant to be uncovered. I personally found myself at a Critical Moment when I realized that there were more than telecom towers at play. As such, the next phase of the project sought to spark this moment in others. But how could it be done by using the same language as the occupier? In this case, occupational language utilized a seemingly innocuous entry onto the island such as providing humanitarian aid and disaster relief, a grey area when compared to blatant and more violent methods of colonial occupation.

At the start of the course, I was quite sure that the Output medium I wanted to explore was a game. However, the case study and site itself was yet to be decided. This thesis could have gone in many directions, just as a game can have multiple endings, side quests, storylines, and characters to discover. The challenge was that I didn’t know how to play this one in the beginning. Nonetheless, I took on the challenge and was rewarded in the end. The next phases, Narrative Implementation and Output, I begin to demonstrate how this thesis functions as a spatial, social, and tactile tool that exposes the imperial-colonial playbook of the UAE, prompting discussion, reactions, and possible long-term plans for Socotra amongst players and beyond.

1. Taiz Time. October 10, 2022. https://twitter.com/TaizTime/status/1579441615311196160

2. Trips with Rosie. December 22, 2023. https://tripswithrosie.com/socotra-island-hidden-paradise-in-the-world/