In Conversation with Hernán Bianchi Benguria

BIOGRAPHY

Hernán is a Human Geography PhD Candidate at UofT; and a licensed architect in Chile with a Master’s in urban development from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and a Master’s in Design Studies in Urbanism, Landscape, and Ecology from Harvard University. He has over a decade of experience in urban, regional, and environmental planning both in the private and public sectors in Chile, having served in Chile’s Ministry of Land as head of the Territorial Studies Department and coordinator for the creation and reconfiguration of numerous official protected areas—including numerous National Parks.

Hernán was a 2022–23 Urban Graduate Fellow at the University of Toronto’s School of Cities and a 2017–18 Canada Program Research Fellow at the Harvard Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Under the supervision of Prof. Scott Prudham, his PhD research focuses on the global transition to electromobility in terms of the political ecology and economy of lithium extraction in Chile. He also participates in the political economy of environment and political ecology ‘PE2’ research group, based in the Department of Geography & Planning and the School of the Environment at UofT. He sits on the board of Open Systems—a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization—collaborating in multimedia exhibitions and publication projects, including the Canadian EXTRACTION Exhibition at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Hernán is a Human Geography PhD Candidate at UofT; and a licensed architect in Chile with a Master’s in urban development from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and a Master’s in Design Studies in Urbanism, Landscape, and Ecology from Harvard University. He has over a decade of experience in urban, regional, and environmental planning both in the private and public sectors in Chile, having served in Chile’s Ministry of Land as head of the Territorial Studies Department and coordinator for the creation and reconfiguration of numerous official protected areas—including numerous National Parks.

Hernán was a 2022–23 Urban Graduate Fellow at the University of Toronto’s School of Cities and a 2017–18 Canada Program Research Fellow at the Harvard Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Under the supervision of Prof. Scott Prudham, his PhD research focuses on the global transition to electromobility in terms of the political ecology and economy of lithium extraction in Chile. He also participates in the political economy of environment and political ecology ‘PE2’ research group, based in the Department of Geography & Planning and the School of the Environment at UofT. He sits on the board of Open Systems—a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization—collaborating in multimedia exhibitions and publication projects, including the Canadian EXTRACTION Exhibition at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Facilitated by the Scaffold* Editorial Team in February 2024.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

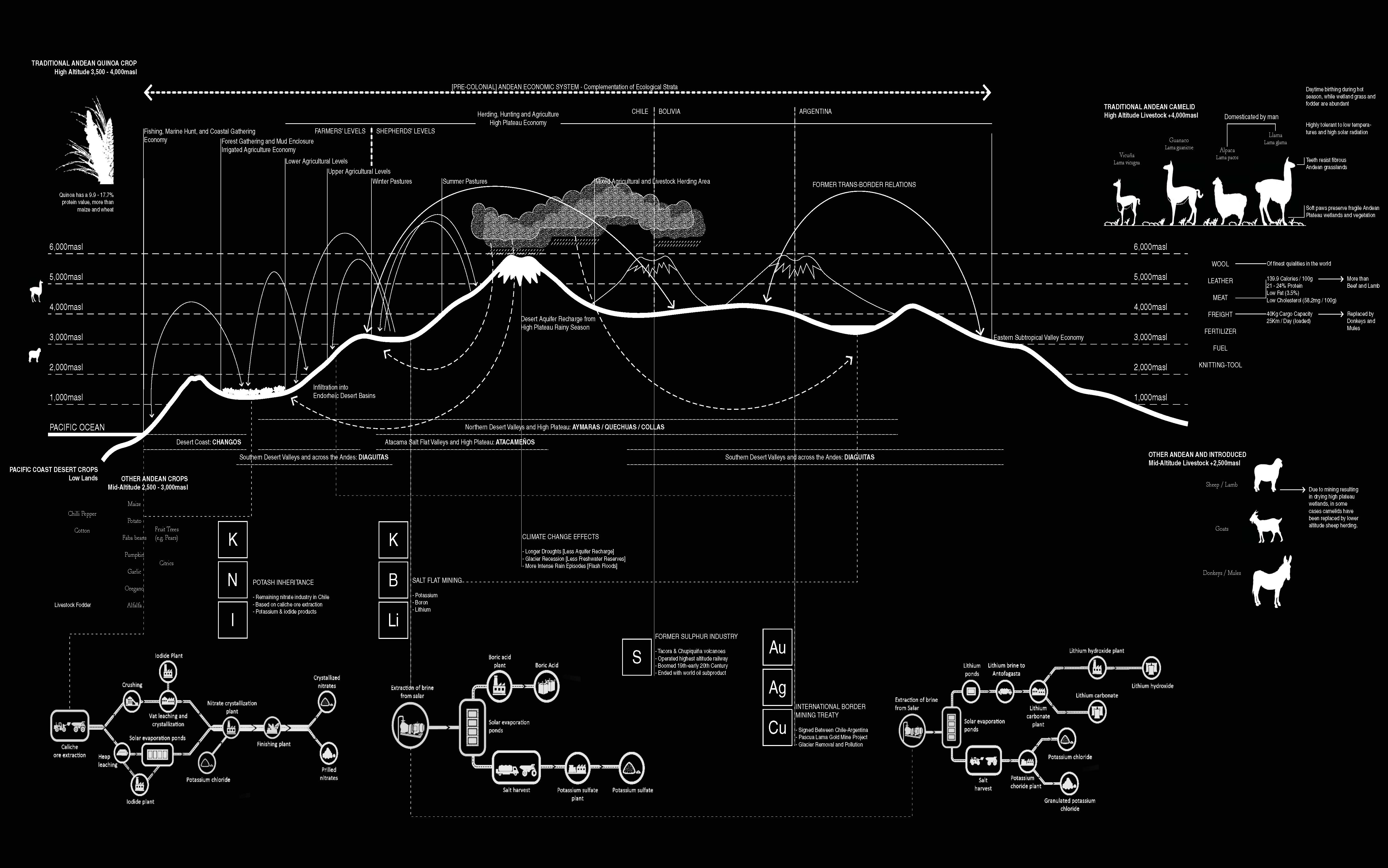

Figure 1. Andean Sectional Economies, 2017. Hernán Bianchi Benguria.

Q: Could you briefly introduce yourself and what the focus of your work has been?

I was born and I grew up between Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. I studied architecture but midway through, I discovered urban planning. I love doing research and thinking more theoretically—just by its scale, planning has its own way of incorporating these elements and having an impact. Following my education, I worked for ten years, in urban planning—both in private practice and in the government. While in public service, I started getting interested in issues of development and conflict—which are fundamental themes of political ecology. To develop any project—from industrial sites to a national park—there are always issues with natural resources, landscape, extraction, or local communities, all of which are topics of interest in the field. This is where I got really interested in political ecology, without knowing of its formal existence.

After I ended my work in the government, I went to the Harvard GSD and did a research program in urbanism, landscape and ecology—this is where it all came together. My focus throughout the program was on extraction and conflict, specifically investigating lithium. Chile’s economy is largely reliant on mining. Extractive activities have been involved in the development of the country for centuries, and the way that this has evolved over time is deeply embedded in the country’s political and economic processes. This was in 2015, when the EV industry had really started to take off. The lithium industry has always been very important in Chile, but this moment led to new interest and speculation. In the following two years, I wrote my thesis on lithium extraction in the northern Chilean Andes. I examined the Atacama salt flats—their history, surrounding conflicts, and politics. I’m now pursuing a PhD further studying this industry.

Q: Was there a key moment or project when you were working in government or working in industry that catalyzed your interest in the extractive industries and your current work?

Everything I did as a government official, allowed me to see how things worked from the inside. In the Ministry of Land, we acted as a sort of realtor for the state—we would create policy around tenure, development, zoning, and work with all different kinds of administration and management. One key project involved a plan to make ten new national parks in Chilean Patagonia. I was put in charge of coordinating the entire process for Yendegaia National Park, which included the merging of private, donated land into a large national park. We created this park in record time, under some conditions that were almost movie-like. When requesting approval from various ministries, we’d sometimes hit a wall or be met with resistance. We’d have one of the president’s advisors move the process forward—and they’d negotiate it in a matter of minutes. When you have access to that kind of power, it’s an entire experience in itself. For me, this was a huge learning experience. It allowed me to access certain knowledge, certain people, and the resources needed to move forward whatever research I was undertaking or the process I was supervising. It opened my eyes to how things work and generally informed the direction of my research.

Then, there was the other side of working for the government. Shortly before I ended my work here, there was a study we had to do around a growing mining city in anticipation of new development. A colleague and I wanted to include Indigenous consultation, because it was an archaeological area, and it was near or within an Indigenous administration area; however, there were people in our ministry refusing this recommendation, stating that the communities would say no to everything we had set out to do. This is when the professional, bureaucratic worlds are forced to confront ethical implications. And this is where I started to realize that many processes purposefully omit certain populations.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 2. Fieldwork Documentation, 2021. Hernán Bianchi Benguria.

Q: Which methods of inquiry have you taken with you from your time in both your design education, work in planning, and policy? Have you adapted any of these or expanded upon them in your current work?

I’ve always used a diverse range of mixed methods.

One of the most productive and important methods I’ve engaged with has been interviews. Interviewing is an entire art. I learned some of what I know from Pierre Bélanger’s extraction seminar, where he taught us how to conduct an interview in order to get the information you’re looking for. At the end of the term, I ended up interviewing the director of Barrick Gold Corporation in Chile. It took me two months to reach this person, but I got my interview. I used all the methods and techniques that Pierre taught us for interviewing high profile people—learn their CV by heart, send questions, but place the really important ones in the middle—and it worked. The work that was produced by the students in that course was truly remarkable.

I’ve also worked with maps, archives, and so on. And then now at a doctorate level research methods are an entire discipline within the program. In terms of my experience, there’s the desk work, and there’s the field work. Either way, the best work takes a lot of digging. With research in the field, you have to keep your eyes open. Whether you do participant observation, semi structured interviews, or on the go interviews, you have to be prepared at all times, because information can come at you at any point in any way.

Q: Much of the work that you’ve done traces timelines of extraction and resistance—from environmental justice movements and literature since 1993, to the colonial history of mining in Chile dating back to the sixteenth century. How has investigating these legacies through a historical lens informed your current research?

I’ve found that timelines are a great way to both represent but also to gather data in a way that you can process it yourself as a researcher. First of all, adding the time variable really raises a representation to another level, it makes it much more informative. I learned this from landscape architects, as they have to constantly consider time, for plantings, seasons, and other variables.

Timelines also help to condense the full perspective of things very quickly. One of the biggest challenges of political ecology is gathering all the angles you want to examine of a particular topic—and the timeline can really help factor what these may be. In complex processes, timelines are helpful devices for helping spatialize events and understand how they happened and evolved. You might start with the ugly Excel sheet or Word document where you put all the dates and all the events, but then you can build upon this to create a graphic that represents both spatial and temporal aspects together. It’s an easy way to pull all this very arid information together into something that can speak to everyone. Anyone can see a timeline and understand it—the medium serves a very broad audience.

![]()

Figure 3. Pascua Lama Timeline, 2016. Hernán Bianchi Benguria.

Q: So, you use timelines in your research process—in gathering and analyzing information—but also in representation.

Right…and every time. It’s kind of funny how often we’ve used this method. I remember in the office, there were a few times where one of us said, we’ve got to promise ourselves to not use a timeline at least once. But at the end of the day, we hit a wall, and we’ve got to go back and do it. It’s a great organizational device, but it also provides this deeper reading beyond just investigating the space.

Q: As a former designer and someone who’s been in that field, do you feel like there are any unique approaches that you’ve brought with you from a design background that other geographers or social scientists might not have?

I’d say the visual and graphic dimensions definitely set design research apart. Mapping, sketching, and photography are great tools for qualitative research. I try to use mixed media as much as I can, although, in the social sciences, it is more of a writing world. Sometimes, graphic materials may not even be accepted for publication. It was a bit of a shock for me; when I switched from the GSD to the PhD in geography, the first emphasized graphics, and now, everything is centered around writing.

It’s not only the visuals you create—it’s also the visuals you analyze. Although people will think that geography is all about maps, it’s all about space and spatial expression of different phenomena. It’s about how you build arguments, and how you use the evidence to develop and prove that argument. Mapping is definitely key. I’m not talking only about formal mapping—I’m talking about how maps can be created to subvert classical notions of space. Mapping is extremely political; they’re used to control, to administrate, and so on. As a researcher in political ecology, you are using maps to also deconstruct these processes.

Q: You’re part of Open Systems, a non-profit collective that investigates socioecological and geopolitical systems through the lenses of environmental justice, sovereignty, and community self-determination, among other areas. The approaches of this collective are concerned with directly countering existing colonial institutions, processes, and systems. Among these are counter-cartography and retroactive mapping. Can you elaborate on these mediums and their significance?

In participating in counter-cartography, you’re really going against what the mapping discipline has been all about, in the colonial capitalist world. It’s a lot about creativity: you have to literally visualize new angles that you would not see from a top down point of view—whether this is in section, across time, in oblique view, or another. Counter-cartography opens up the possibility to use anything as a map. Mapping can be done in any scale, with any medium, in any way, and take into account any kind of variable. The openness of the medium is really the spirit of Open Systems—it’s an open system that could evolve into many different things at the end of the day.

Q: The OPSYS manifesto describes architecture without architects and urbanism without urbanists.[1] Beyond a call to legitimize bottom-up approaches and local knowledge and intelligence, what does this look like?

It’s really about the omitted or overlooked knowledge and communities—and everything that is lost, erased, appropriated, and stolen through the imposition of so-called professionals. So often, the architect is leading the design process. What if we thought of the bricklayer, or local communities, as the head of the process instead? It’s all about acknowledging communities, respecting and honoring the craft of people. On the flip side, these are the things that are destroyed, lost, and erased—and then re-appropriated through extraction and through extractive processes. The central philosophy of the manifesto is to go upstream. So it’s not about the water you get, it’s about where the water comes from, and how it’s treated at the source.

![]()

Figure 4. Andean Almanac, 2017. Hernán Bianchi Benguria.

Q: From your experience, what does it look like for architects and designers to engage with questions of colonization and territory?

If I have to put it simply—resist denial. I think there’s an issue of denial in professions in general. Denial sometimes is conscious and purposely mobilized, but other times it just comes with the system. Pierre Bélanger frequently brought up John K. Galbraith’s book during lecture—The New Industrial State. [2] It basically explains that we work and live in organizations. Everything around us comes from a process that is managed from institutions—from private companies to state institutions. The bigger they are, the more immersed our existence is within these systems.

Denial is sometimes purposeful—where people want to make a profit or have certain interests. This is the easier, and probably our most familiar, understanding of denial. On the other side, denial becomes embedded in us through the organizational systems that we coexist with. Just like social ecologists recognize a dialectical process between nature and society, there is also a dialectical relationship between living beings and organization systems.

Rosalind Williams, a technology theorist and historian from MIT, has written about how things around us are linked and organized. [3] In going back to methods of counter-cartography and counter-design, we are countering the existing organization of things. If you are to take down states, empires, and entire imperial projects, you have to find ways around the system’s formal organization. That, for me, is true subversion—a questioning or attempt to break with denial.

Q: How might designers and researchers integrate these principles into their work?

I think the biggest challenge by far is not only asking why you’re doing the research you’re doing, but what its contribution will be. I’m not talking about knowledge or stacking your thesis in an archive. I’m talking about what the contribution is to your research subjects and the communities you’re engaging with. There’s a certain ethical angle to the discipline where you have to examine yourself and see what you’re doing in these peoples’ lives. As a researcher, you’re entering someone else’s existence to extract information—but how is this helping people with their struggles? Are you being helpful or just collecting data and taking off? It’s a hard question to answer. But in the end, it’s this inquiry that keeps you alert; on the one hand not to be extractive, but also on the other to really question and repurpose your research towards the community you’re engaging. Then again, sometimes that answer is not known at the very beginning.

Spatial justice starts with whoever is declaring it or looking at it in a grounded way. This may not necessarily start within the academic world, which in itself is a colonial institution that is extremely hierarchical and structured. So it becomes a matter of trying to have a foot on each side—one on the shore, one on the ship. It’s difficult, but it may also potentially give a reason to what you’re doing. It forces you to find purpose, if you really want to.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Andean Sectional Economies, 2017. Hernán Bianchi Benguria.

Q: Could you briefly introduce yourself and what the focus of your work has been?

I was born and I grew up between Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. I studied architecture but midway through, I discovered urban planning. I love doing research and thinking more theoretically—just by its scale, planning has its own way of incorporating these elements and having an impact. Following my education, I worked for ten years, in urban planning—both in private practice and in the government. While in public service, I started getting interested in issues of development and conflict—which are fundamental themes of political ecology. To develop any project—from industrial sites to a national park—there are always issues with natural resources, landscape, extraction, or local communities, all of which are topics of interest in the field. This is where I got really interested in political ecology, without knowing of its formal existence.

After I ended my work in the government, I went to the Harvard GSD and did a research program in urbanism, landscape and ecology—this is where it all came together. My focus throughout the program was on extraction and conflict, specifically investigating lithium. Chile’s economy is largely reliant on mining. Extractive activities have been involved in the development of the country for centuries, and the way that this has evolved over time is deeply embedded in the country’s political and economic processes. This was in 2015, when the EV industry had really started to take off. The lithium industry has always been very important in Chile, but this moment led to new interest and speculation. In the following two years, I wrote my thesis on lithium extraction in the northern Chilean Andes. I examined the Atacama salt flats—their history, surrounding conflicts, and politics. I’m now pursuing a PhD further studying this industry.

Q: Was there a key moment or project when you were working in government or working in industry that catalyzed your interest in the extractive industries and your current work?

Everything I did as a government official, allowed me to see how things worked from the inside. In the Ministry of Land, we acted as a sort of realtor for the state—we would create policy around tenure, development, zoning, and work with all different kinds of administration and management. One key project involved a plan to make ten new national parks in Chilean Patagonia. I was put in charge of coordinating the entire process for Yendegaia National Park, which included the merging of private, donated land into a large national park. We created this park in record time, under some conditions that were almost movie-like. When requesting approval from various ministries, we’d sometimes hit a wall or be met with resistance. We’d have one of the president’s advisors move the process forward—and they’d negotiate it in a matter of minutes. When you have access to that kind of power, it’s an entire experience in itself. For me, this was a huge learning experience. It allowed me to access certain knowledge, certain people, and the resources needed to move forward whatever research I was undertaking or the process I was supervising. It opened my eyes to how things work and generally informed the direction of my research.

Then, there was the other side of working for the government. Shortly before I ended my work here, there was a study we had to do around a growing mining city in anticipation of new development. A colleague and I wanted to include Indigenous consultation, because it was an archaeological area, and it was near or within an Indigenous administration area; however, there were people in our ministry refusing this recommendation, stating that the communities would say no to everything we had set out to do. This is when the professional, bureaucratic worlds are forced to confront ethical implications. And this is where I started to realize that many processes purposefully omit certain populations.

Figure 2. Fieldwork Documentation, 2021. Hernán Bianchi Benguria.

Q: Which methods of inquiry have you taken with you from your time in both your design education, work in planning, and policy? Have you adapted any of these or expanded upon them in your current work?

I’ve always used a diverse range of mixed methods.

One of the most productive and important methods I’ve engaged with has been interviews. Interviewing is an entire art. I learned some of what I know from Pierre Bélanger’s extraction seminar, where he taught us how to conduct an interview in order to get the information you’re looking for. At the end of the term, I ended up interviewing the director of Barrick Gold Corporation in Chile. It took me two months to reach this person, but I got my interview. I used all the methods and techniques that Pierre taught us for interviewing high profile people—learn their CV by heart, send questions, but place the really important ones in the middle—and it worked. The work that was produced by the students in that course was truly remarkable.

“With research in the field, you have to keep your eyes open. Whether you do participant observation, semi structured interviews, or on the go interviews, you have to be prepared at all times, because information can come at you at any point in any way.”

I’ve also worked with maps, archives, and so on. And then now at a doctorate level research methods are an entire discipline within the program. In terms of my experience, there’s the desk work, and there’s the field work. Either way, the best work takes a lot of digging. With research in the field, you have to keep your eyes open. Whether you do participant observation, semi structured interviews, or on the go interviews, you have to be prepared at all times, because information can come at you at any point in any way.

Q: Much of the work that you’ve done traces timelines of extraction and resistance—from environmental justice movements and literature since 1993, to the colonial history of mining in Chile dating back to the sixteenth century. How has investigating these legacies through a historical lens informed your current research?

I’ve found that timelines are a great way to both represent but also to gather data in a way that you can process it yourself as a researcher. First of all, adding the time variable really raises a representation to another level, it makes it much more informative. I learned this from landscape architects, as they have to constantly consider time, for plantings, seasons, and other variables.

Timelines also help to condense the full perspective of things very quickly. One of the biggest challenges of political ecology is gathering all the angles you want to examine of a particular topic—and the timeline can really help factor what these may be. In complex processes, timelines are helpful devices for helping spatialize events and understand how they happened and evolved. You might start with the ugly Excel sheet or Word document where you put all the dates and all the events, but then you can build upon this to create a graphic that represents both spatial and temporal aspects together. It’s an easy way to pull all this very arid information together into something that can speak to everyone. Anyone can see a timeline and understand it—the medium serves a very broad audience.

Figure 3. Pascua Lama Timeline, 2016. Hernán Bianchi Benguria.

Q: So, you use timelines in your research process—in gathering and analyzing information—but also in representation.

Right…and every time. It’s kind of funny how often we’ve used this method. I remember in the office, there were a few times where one of us said, we’ve got to promise ourselves to not use a timeline at least once. But at the end of the day, we hit a wall, and we’ve got to go back and do it. It’s a great organizational device, but it also provides this deeper reading beyond just investigating the space.

Q: As a former designer and someone who’s been in that field, do you feel like there are any unique approaches that you’ve brought with you from a design background that other geographers or social scientists might not have?

I’d say the visual and graphic dimensions definitely set design research apart. Mapping, sketching, and photography are great tools for qualitative research. I try to use mixed media as much as I can, although, in the social sciences, it is more of a writing world. Sometimes, graphic materials may not even be accepted for publication. It was a bit of a shock for me; when I switched from the GSD to the PhD in geography, the first emphasized graphics, and now, everything is centered around writing.

It’s not only the visuals you create—it’s also the visuals you analyze. Although people will think that geography is all about maps, it’s all about space and spatial expression of different phenomena. It’s about how you build arguments, and how you use the evidence to develop and prove that argument. Mapping is definitely key. I’m not talking only about formal mapping—I’m talking about how maps can be created to subvert classical notions of space. Mapping is extremely political; they’re used to control, to administrate, and so on. As a researcher in political ecology, you are using maps to also deconstruct these processes.

“In participating in counter-cartography, you’re really going against what the mapping discipline has been all about, in the colonial capitalist world.”

Q: You’re part of Open Systems, a non-profit collective that investigates socioecological and geopolitical systems through the lenses of environmental justice, sovereignty, and community self-determination, among other areas. The approaches of this collective are concerned with directly countering existing colonial institutions, processes, and systems. Among these are counter-cartography and retroactive mapping. Can you elaborate on these mediums and their significance?

In participating in counter-cartography, you’re really going against what the mapping discipline has been all about, in the colonial capitalist world. It’s a lot about creativity: you have to literally visualize new angles that you would not see from a top down point of view—whether this is in section, across time, in oblique view, or another. Counter-cartography opens up the possibility to use anything as a map. Mapping can be done in any scale, with any medium, in any way, and take into account any kind of variable. The openness of the medium is really the spirit of Open Systems—it’s an open system that could evolve into many different things at the end of the day.

Q: The OPSYS manifesto describes architecture without architects and urbanism without urbanists.[1] Beyond a call to legitimize bottom-up approaches and local knowledge and intelligence, what does this look like?

It’s really about the omitted or overlooked knowledge and communities—and everything that is lost, erased, appropriated, and stolen through the imposition of so-called professionals. So often, the architect is leading the design process. What if we thought of the bricklayer, or local communities, as the head of the process instead? It’s all about acknowledging communities, respecting and honoring the craft of people. On the flip side, these are the things that are destroyed, lost, and erased—and then re-appropriated through extraction and through extractive processes. The central philosophy of the manifesto is to go upstream. So it’s not about the water you get, it’s about where the water comes from, and how it’s treated at the source.

Figure 4. Andean Almanac, 2017. Hernán Bianchi Benguria.

Q: From your experience, what does it look like for architects and designers to engage with questions of colonization and territory?

If I have to put it simply—resist denial. I think there’s an issue of denial in professions in general. Denial sometimes is conscious and purposely mobilized, but other times it just comes with the system. Pierre Bélanger frequently brought up John K. Galbraith’s book during lecture—The New Industrial State. [2] It basically explains that we work and live in organizations. Everything around us comes from a process that is managed from institutions—from private companies to state institutions. The bigger they are, the more immersed our existence is within these systems.

Denial is sometimes purposeful—where people want to make a profit or have certain interests. This is the easier, and probably our most familiar, understanding of denial. On the other side, denial becomes embedded in us through the organizational systems that we coexist with. Just like social ecologists recognize a dialectical process between nature and society, there is also a dialectical relationship between living beings and organization systems.

Rosalind Williams, a technology theorist and historian from MIT, has written about how things around us are linked and organized. [3] In going back to methods of counter-cartography and counter-design, we are countering the existing organization of things. If you are to take down states, empires, and entire imperial projects, you have to find ways around the system’s formal organization. That, for me, is true subversion—a questioning or attempt to break with denial.

“If I have to put it simply—resist denial. I think there’s an issue of denial in professions in general. Denial sometimes is conscious and purposely mobilized, but other times it just comes with the system.”

Q: How might designers and researchers integrate these principles into their work?

I think the biggest challenge by far is not only asking why you’re doing the research you’re doing, but what its contribution will be. I’m not talking about knowledge or stacking your thesis in an archive. I’m talking about what the contribution is to your research subjects and the communities you’re engaging with. There’s a certain ethical angle to the discipline where you have to examine yourself and see what you’re doing in these peoples’ lives. As a researcher, you’re entering someone else’s existence to extract information—but how is this helping people with their struggles? Are you being helpful or just collecting data and taking off? It’s a hard question to answer. But in the end, it’s this inquiry that keeps you alert; on the one hand not to be extractive, but also on the other to really question and repurpose your research towards the community you’re engaging. Then again, sometimes that answer is not known at the very beginning.

Spatial justice starts with whoever is declaring it or looking at it in a grounded way. This may not necessarily start within the academic world, which in itself is a colonial institution that is extremely hierarchical and structured. So it becomes a matter of trying to have a foot on each side—one on the shore, one on the ship. It’s difficult, but it may also potentially give a reason to what you’re doing. It forces you to find purpose, if you really want to.

1. “Manifesto - Open Systems,” No Design on Stolen Land, 2023, https://nodesignonstolen.land/manifesto.2. J.K Galbraith,

The New Industrial State (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967).3. Rosalind Williams, “Cultural Origins and Environmental Implications of Large Technological Systems,” Science in Context 6, no. 2 (1993): 377–403.