Children of Heaven

HOOMAN MOSHREFZADEH

I am a current undergraduate student in the Architectural Studies program. My interests include vernacular architecture and community-based urban design. Born in a small port town in Southern Iran, my early childhood was defined by frequently moving across the country. This experience inspired an early interest in spaces built around local community needs and traditional building practices. I began my studies in Architectural Studies at the University of Toronto in 2021, which has led me to work collaboratively on local and international design projects involving community research and interaction.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

Figure 1. Notebook sketches of Karim and his friends, Fez, June 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

A refuge from the sun’s heat, the winding streets of the Medina of Fez form an irregular, yet cohesive system of paths to explore the city. Formed almost organically, the streetscape of Fez embodies the typological Islamic city’s urban fabric. Its unique street pattern is a result of a spontaneous urban growth representative of the inverse of the modern Western city. Whereas the Western city is built on a system of pre-established lots and streets, Fez developed its street pattern according to the placement of its buildings.

I had travelled to Morocco to explore the architectural past of the city, while facing its current urban challenges as part of a summer studio course offered by the University of Toronto in collaboration with the Euro-Mediterranean University of Fez. Thus, my time in Fez as an architecture student was defined through the exploration of this unique streetscape.

Although I resided in a secluded dormitory offered by the university, my days were defined by trips to the bustling old city. Often lost in its network of streets and alleys, I began to build a subconscious map of the city through a sense of familiarity. Recognizing local features and landmarks informed my sense of direction and allowed me to navigate my path through the narrow and packed streets. Among the close-packed buildings that guided the flow of my path, I began to notice pockets of empty space which disrupted the otherwise consistent flow of connecting facades. A hole in the urban fabric, these gaps frequently appeared on residential streets. It was clear that the gaps suggested the absence of a building; a structural phantom haunted these sites.

Through my Moroccan colleagues, I learned that these gaps were the result of demolished family homes. Once inhabited by Fassi families, they had been abandoned by their former owners and subsequently demolished due to gradual structural damage.[1] The reasons for their leave were complex. Oftentimes families would leave their traditional homes for the modern Ville Nouvelle.[2] At other times, the care of the house would be lost in inheritance disputes. However, these gaps also presented an opportunity for a new development in the dense urban fabric of the city—public spaces. Traditionally, certain instances of public space—according to the Western definition of the concept—do not exist in the Islamic city. This includes recreational spaces, from parks to squares; and other instances of public space which appear in Western urbanism. Instead, Islamic public spaces were reserved for non-recreational uses: mosques for prayer, madrasas for education, and markets for commerce.

![]()

![]()

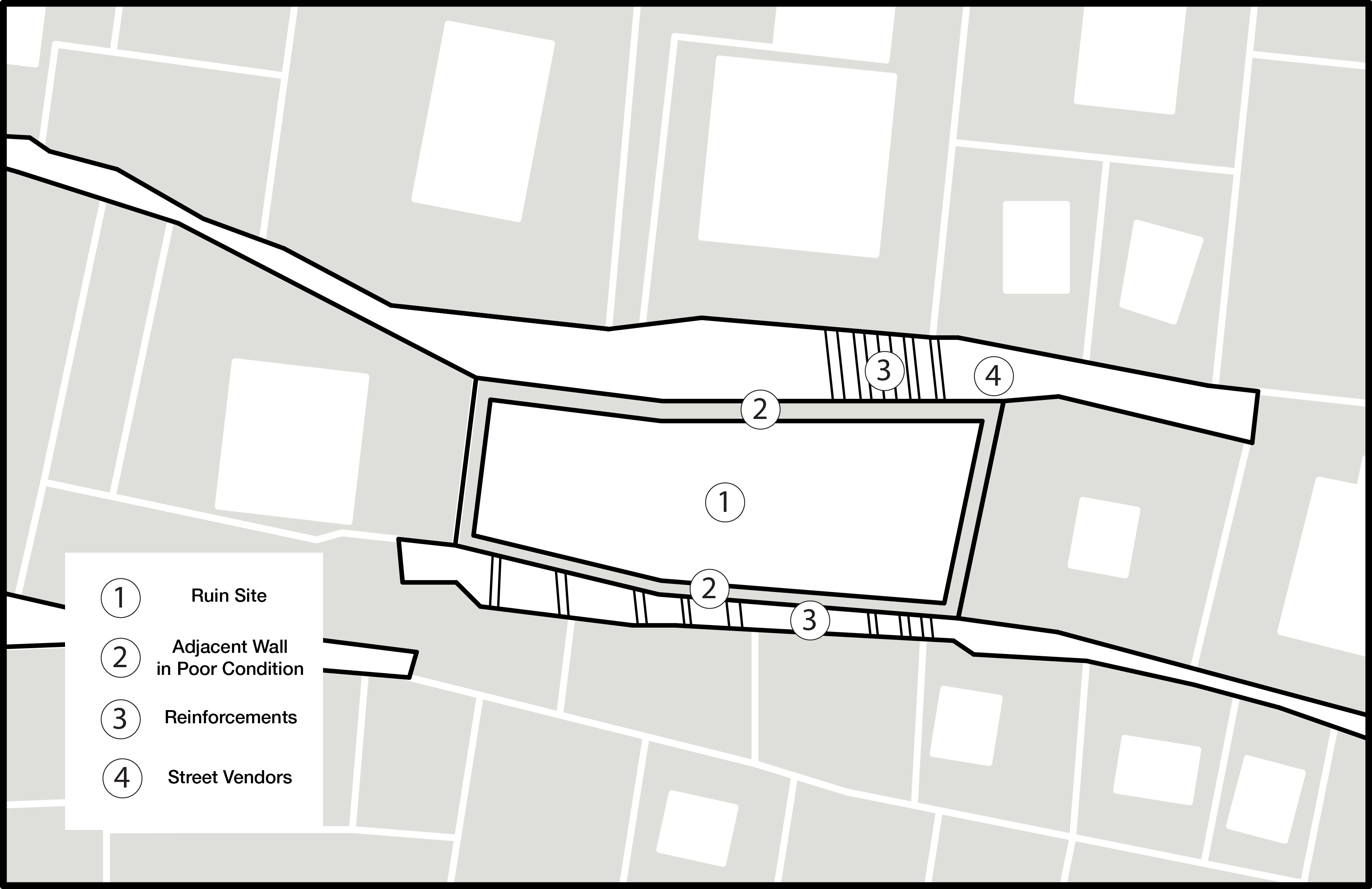

Figure 2. Site Map of a Demolished Home with Original Exterior Walls, Fez, May 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

Figure 3. Inventory Map of Research Site, Fez, May 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

Due to their potential for implementing new public spaces, these urban gaps became the focus of my design studio in Fez. We began collecting data regarding these sites, working together to create a map of the city, identifying the location and condition of similar urban gaps. With three specific sites selected, we then began working in teams to further gather site context. Each team took up research for one of the chosen sites and collected data regarding its spatial characteristics through a mix of map making and photographic documentation.

Some of our strategies included creating maps of the physical features affecting the experience on site, or counting the people moving through it at specific hours. The research data also included information on modes of movement, from walking, to running, to riding a bicycle; to time spent on site, and types of stationary activities, such as socializing, exercise, or eating. To better understand the type of public space that would benefit the local community best, we conducted a series of surveys which asked participants about their vision for the site. With the help of our Moroccan colleagues, we initiated conversation with the locals to become familiar with them and the history of their neighbourhood. Through countless site visits and analyses, we were able to build an understanding of the site which could then inform our design process.

During my visits to the site, I would often find myself the subject of curious eyes. Children passing by would pause and observe me from a distance as I took notes or made sketches, presumably wondering as to what I was doing in their secluded enclave. On one occasion, a boy approached me as I was sketching on site. I responded to his curious stare with a smile, but his eyes were set on what I held in my hands: a pen and pad of paper.

![]()

![]()

The Exterior Walls of a Demolished Home Showing Signs of Decay, Fez, May 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

Figure 5. Hassan drawing on a wall with chalk, Fez, May 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

It became clear to me that the boy was rather interested in my sketches and the notebook I held. I offered him my pen and notebook as a friendly gesture, which he eagerly accepted. Since we were unable to speak each other’s language, we began drawing and communicating using the notebook. He chose drawing subjects from a wide array of interests—including cartoon characters, footballers, or portraits of friends. Through his conversations with my colleague in Darija, I learned that his name was Karim.[3] During my subsequent site visits, I saw more of Karim and became familiar with his friends, Issam and Hassan. Aside from their shared love for football, Karim’s friends also shared his interest in drawing in the notebook.

Seeing the creativity that the children showed through their drawings, we felt it appropriate to include them in design discussions regarding the site. However, we found conversing with them to be a limiting form of communication as the majority of our team did not speak Darija. Instead, we encouraged them to express themselves in their preferred medium of drawing. This would allow us to understand their perspective without the use of tongues, with no words or nuance lost in translation. The children had no interest in drawing maps as we did, nor did they care to depict the same features. Instead, they chose to draw what they wanted to see. They rejected an analytical perspective, but remained genuine to the site conditions which affected them.

Noticing their continuous interest in our presence on site, we began to organize a workshop for the children where they could express their desires for the site, preparing snacks, and self-expressive worksheets. “Bring your friends from the neighbourhood,” we told Karim. “We will bring pencils for you to draw, and have plenty of food and juice. Afterwards we may play football.” On the day of the workshop, Karim, Issam, and Hassan returned with friends from the neighbourhood who were eager to participate.

We handed out worksheets and colouring pencils to the children so that they might draw their ideal public space, sitting with them as they began drawing, chatting, and eating. During the workshop, we observed that the children were sociable and collaborative, exchanging ideas and showing their drawings to one another. This collaboration culminated in several ideas that persisted in most drawings, namely the motif of playing fields and outdoor pools. However, these proposals were ambitious in their scale and constructability, which made them impossible to implement given the site’s limited size. In addition, many of the locals had opposed the ideas as they believed that football fields would invite rowdiness and noise. Outdoor pools were also an impossibility due to the city’s water shortage and the challenges of constructing one on site.

While football fields and outdoor pools might not be practical, they gave insight into Karim and his friends’ desires. Using my observations and experiences on site, I attempted to interpret what these desires translated to in a figurative sense. The two persisting motifs were simplified into two concepts: play and comfort.

![]()

![]()

Figure 6. Drawing alongside Karim and his Friends, Fez, June 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

Figure 7. Final Drawings of the Children, Fez, June 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

For Karim and his friends, play symbolized a desire for physical activity. It represented the need to run, laugh, kick a ball, and scrape one’s knees, all experienced by many boys in childhood. For young boys, physical activity also becomes an integral part of their social lives, as it presents an opportunity for conversation and the exchange of ideas. The concept of comfort thus symbolized a retreat from the troubles of childhood. It represented an escape from the responsibilities of school, or a refuge from the summer heat. Comfort did not only equate physical comforts but a broader desire for a sanctuary. Amongst the children, the concept of play was most evident in drawings of football fields, which signified a space to play and socialize with friends; whereas comfort could be seen in representations of water and pools, which expressed a refuge from the heat and a space to cool off.

We understood that our design approach had to respond to this need for play and comfort. If the space was to ever be utilized by children, it had to be in dialogue with those needs. Based on our interpretation of the two concepts, we formed a number of spaces that could embody those desires on site. A football field remained an impossibility due to size constraints; however, it was evident that the children still enjoyed the sport, and that there should be adequate open space for games. Alternatively, a vertical playground would provide an engaging space for physical activity without disturbing the site’s openness. The outdoor pool was exchanged for a spray pool with integrated ground water features, creating minimal spatial obstructions and water usage. There was also recognition of a need for a place of rest and shade to contrast the physicality of play.

Ultimately, the drawings provided my group with a guide outlining the children’s ambitions for their community public space. Despite the lack of verbal communication, the drawings enabled an exchange of possible design solutions. They revealed a juvenile perspective that was not grounded by analytical research or design conventions, but rather presented an imagination ignorant of those realities.

As I watched Karim and his friends draw, I was reminded of Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince; where he contrasts the realism of adults with the imagination of children.[4] He recounts a childhood memory where despite proudly presenting his drawing of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant to adults, his efforts are belittled as the adults mistake the illustration for a hat. In response, the young Saint-Exupery creates a section drawing of the boa constrictor, showing the previously hidden elephant inside the snake. Similar to Saint-Exupery, the boys had no interest in the realism of maps, diagrams, or sections of boa constrictors; instead, drawing what they saw, by seeing what they cared for, and caring for what brought laughter.

I am a current undergraduate student in the Architectural Studies program. My interests include vernacular architecture and community-based urban design. Born in a small port town in Southern Iran, my early childhood was defined by frequently moving across the country. This experience inspired an early interest in spaces built around local community needs and traditional building practices. I began my studies in Architectural Studies at the University of Toronto in 2021, which has led me to work collaboratively on local and international design projects involving community research and interaction.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Notebook sketches of Karim and his friends, Fez, June 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

A refuge from the sun’s heat, the winding streets of the Medina of Fez form an irregular, yet cohesive system of paths to explore the city. Formed almost organically, the streetscape of Fez embodies the typological Islamic city’s urban fabric. Its unique street pattern is a result of a spontaneous urban growth representative of the inverse of the modern Western city. Whereas the Western city is built on a system of pre-established lots and streets, Fez developed its street pattern according to the placement of its buildings.

I had travelled to Morocco to explore the architectural past of the city, while facing its current urban challenges as part of a summer studio course offered by the University of Toronto in collaboration with the Euro-Mediterranean University of Fez. Thus, my time in Fez as an architecture student was defined through the exploration of this unique streetscape.

“It was clear that the gaps suggested the absence of a building; a structural phantom haunted these sites.”

Although I resided in a secluded dormitory offered by the university, my days were defined by trips to the bustling old city. Often lost in its network of streets and alleys, I began to build a subconscious map of the city through a sense of familiarity. Recognizing local features and landmarks informed my sense of direction and allowed me to navigate my path through the narrow and packed streets. Among the close-packed buildings that guided the flow of my path, I began to notice pockets of empty space which disrupted the otherwise consistent flow of connecting facades. A hole in the urban fabric, these gaps frequently appeared on residential streets. It was clear that the gaps suggested the absence of a building; a structural phantom haunted these sites.

Through my Moroccan colleagues, I learned that these gaps were the result of demolished family homes. Once inhabited by Fassi families, they had been abandoned by their former owners and subsequently demolished due to gradual structural damage.[1] The reasons for their leave were complex. Oftentimes families would leave their traditional homes for the modern Ville Nouvelle.[2] At other times, the care of the house would be lost in inheritance disputes. However, these gaps also presented an opportunity for a new development in the dense urban fabric of the city—public spaces. Traditionally, certain instances of public space—according to the Western definition of the concept—do not exist in the Islamic city. This includes recreational spaces, from parks to squares; and other instances of public space which appear in Western urbanism. Instead, Islamic public spaces were reserved for non-recreational uses: mosques for prayer, madrasas for education, and markets for commerce.

Figure 2. Site Map of a Demolished Home with Original Exterior Walls, Fez, May 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

Figure 3. Inventory Map of Research Site, Fez, May 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

Due to their potential for implementing new public spaces, these urban gaps became the focus of my design studio in Fez. We began collecting data regarding these sites, working together to create a map of the city, identifying the location and condition of similar urban gaps. With three specific sites selected, we then began working in teams to further gather site context. Each team took up research for one of the chosen sites and collected data regarding its spatial characteristics through a mix of map making and photographic documentation.

Some of our strategies included creating maps of the physical features affecting the experience on site, or counting the people moving through it at specific hours. The research data also included information on modes of movement, from walking, to running, to riding a bicycle; to time spent on site, and types of stationary activities, such as socializing, exercise, or eating. To better understand the type of public space that would benefit the local community best, we conducted a series of surveys which asked participants about their vision for the site. With the help of our Moroccan colleagues, we initiated conversation with the locals to become familiar with them and the history of their neighbourhood. Through countless site visits and analyses, we were able to build an understanding of the site which could then inform our design process.

During my visits to the site, I would often find myself the subject of curious eyes. Children passing by would pause and observe me from a distance as I took notes or made sketches, presumably wondering as to what I was doing in their secluded enclave. On one occasion, a boy approached me as I was sketching on site. I responded to his curious stare with a smile, but his eyes were set on what I held in my hands: a pen and pad of paper.

The Exterior Walls of a Demolished Home Showing Signs of Decay, Fez, May 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

Figure 5. Hassan drawing on a wall with chalk, Fez, May 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

It became clear to me that the boy was rather interested in my sketches and the notebook I held. I offered him my pen and notebook as a friendly gesture, which he eagerly accepted. Since we were unable to speak each other’s language, we began drawing and communicating using the notebook. He chose drawing subjects from a wide array of interests—including cartoon characters, footballers, or portraits of friends. Through his conversations with my colleague in Darija, I learned that his name was Karim.[3] During my subsequent site visits, I saw more of Karim and became familiar with his friends, Issam and Hassan. Aside from their shared love for football, Karim’s friends also shared his interest in drawing in the notebook.

Seeing the creativity that the children showed through their drawings, we felt it appropriate to include them in design discussions regarding the site. However, we found conversing with them to be a limiting form of communication as the majority of our team did not speak Darija. Instead, we encouraged them to express themselves in their preferred medium of drawing. This would allow us to understand their perspective without the use of tongues, with no words or nuance lost in translation. The children had no interest in drawing maps as we did, nor did they care to depict the same features. Instead, they chose to draw what they wanted to see. They rejected an analytical perspective, but remained genuine to the site conditions which affected them.

“Instead, we encouraged them to express themselves in their preferred medium of drawing. This would allow us to understand their perspective without the use of tongues, with no words or nuance lost in translation.”

Noticing their continuous interest in our presence on site, we began to organize a workshop for the children where they could express their desires for the site, preparing snacks, and self-expressive worksheets. “Bring your friends from the neighbourhood,” we told Karim. “We will bring pencils for you to draw, and have plenty of food and juice. Afterwards we may play football.” On the day of the workshop, Karim, Issam, and Hassan returned with friends from the neighbourhood who were eager to participate.

We handed out worksheets and colouring pencils to the children so that they might draw their ideal public space, sitting with them as they began drawing, chatting, and eating. During the workshop, we observed that the children were sociable and collaborative, exchanging ideas and showing their drawings to one another. This collaboration culminated in several ideas that persisted in most drawings, namely the motif of playing fields and outdoor pools. However, these proposals were ambitious in their scale and constructability, which made them impossible to implement given the site’s limited size. In addition, many of the locals had opposed the ideas as they believed that football fields would invite rowdiness and noise. Outdoor pools were also an impossibility due to the city’s water shortage and the challenges of constructing one on site.

While football fields and outdoor pools might not be practical, they gave insight into Karim and his friends’ desires. Using my observations and experiences on site, I attempted to interpret what these desires translated to in a figurative sense. The two persisting motifs were simplified into two concepts: play and comfort.

Figure 6. Drawing alongside Karim and his Friends, Fez, June 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

Figure 7. Final Drawings of the Children, Fez, June 2023. Hooman Moshrefzadeh.

For Karim and his friends, play symbolized a desire for physical activity. It represented the need to run, laugh, kick a ball, and scrape one’s knees, all experienced by many boys in childhood. For young boys, physical activity also becomes an integral part of their social lives, as it presents an opportunity for conversation and the exchange of ideas. The concept of comfort thus symbolized a retreat from the troubles of childhood. It represented an escape from the responsibilities of school, or a refuge from the summer heat. Comfort did not only equate physical comforts but a broader desire for a sanctuary. Amongst the children, the concept of play was most evident in drawings of football fields, which signified a space to play and socialize with friends; whereas comfort could be seen in representations of water and pools, which expressed a refuge from the heat and a space to cool off.

We understood that our design approach had to respond to this need for play and comfort. If the space was to ever be utilized by children, it had to be in dialogue with those needs. Based on our interpretation of the two concepts, we formed a number of spaces that could embody those desires on site. A football field remained an impossibility due to size constraints; however, it was evident that the children still enjoyed the sport, and that there should be adequate open space for games. Alternatively, a vertical playground would provide an engaging space for physical activity without disturbing the site’s openness. The outdoor pool was exchanged for a spray pool with integrated ground water features, creating minimal spatial obstructions and water usage. There was also recognition of a need for a place of rest and shade to contrast the physicality of play.

“They revealed a juvenile perspective that was not grounded by analytical research or design conventions, but rather presented an imagination ignorant of those realities.”

Ultimately, the drawings provided my group with a guide outlining the children’s ambitions for their community public space. Despite the lack of verbal communication, the drawings enabled an exchange of possible design solutions. They revealed a juvenile perspective that was not grounded by analytical research or design conventions, but rather presented an imagination ignorant of those realities.

As I watched Karim and his friends draw, I was reminded of Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince; where he contrasts the realism of adults with the imagination of children.[4] He recounts a childhood memory where despite proudly presenting his drawing of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant to adults, his efforts are belittled as the adults mistake the illustration for a hat. In response, the young Saint-Exupery creates a section drawing of the boa constrictor, showing the previously hidden elephant inside the snake. Similar to Saint-Exupery, the boys had no interest in the realism of maps, diagrams, or sections of boa constrictors; instead, drawing what they saw, by seeing what they cared for, and caring for what brought laughter.

1. “Fassi” is the demonym for people originating from Fez.

2. “New Town” built during the period of the French Protectorate.3. The names of all persons mentioned have been changed to preserve their privacy. 4. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock Puffin Books, 1943).

2. “New Town” built during the period of the French Protectorate.3. The names of all persons mentioned have been changed to preserve their privacy. 4. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock Puffin Books, 1943).