A Community Fight

ISAAC SOARES

I’m a Daniels design student with a background in Environmental Science, currently engaged in a project combating gentrification in Little Jamaica. My research spans various roles, from studying early modernist environmentalist architects under Prof. Hans Ibelings, to exploring local ecologies for a school competition in Prague, to investigating changes in Georgian townhomes in London. I run a freelance architectural practice, working on projects throughout the GTA, particularly in missing middle densification, such as laneway homes and multiunit residences. In my free time, I enjoy biking, camping, and traveling. One of my favorite activities is building models or anything hands-on, stemming from my interest in construction work during summers.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

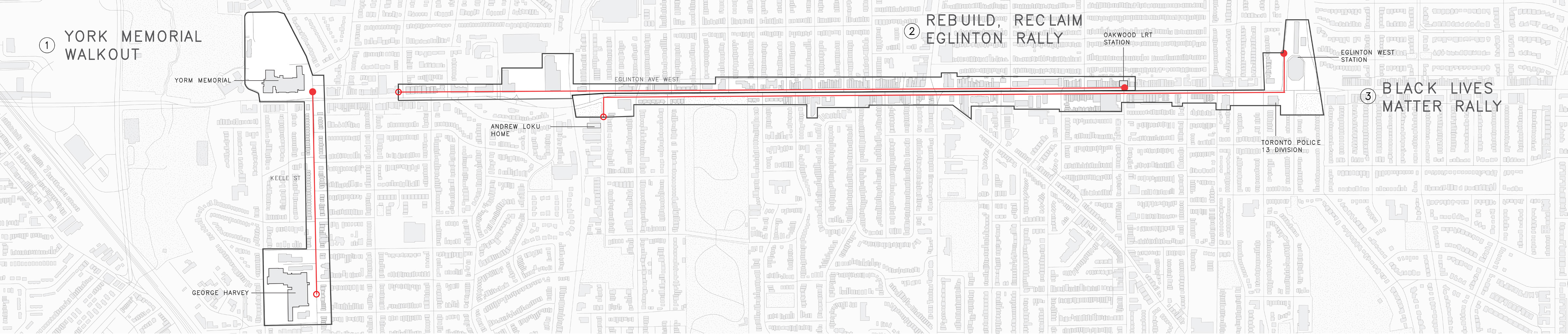

Figure 1. Rebuild, Reclaim Litte Jamaica March, Little Jamaica, August 29, 2020. Reclaim Eg West, 2023. Isaac Soares.

My thesis project focuses on transit-induced gentrification in Little Jamaica, also addressing issues of discrimination, disinvestment, and poor public services. In the first part of my project, I explore various protests and movements to understand the stories, actors, and events that led to these demonstrations. This provides a deeper understanding of the current and historical issues experienced. By speaking to residents and advocates, I construct stories based on resident accounts - which often differ from news media.

(DE)CONSTRUCTING NARRATIVES

The early stages of my research stemmed from mainstream media, through which I used different search filters—keywords, dates, and locations—to locate relevant publications. I read through these articles and took note of the organizations, protesters, and organizer names. (These figures would be important for conducting alternative research later on). After reading multiple articles on each of the three protests, I was able to identify many emerging patterns and similarities.

Mainstream news sources such as CP24, CBC, and the Toronto Star generally followed a similar narrative and included the same information. The stories were often constructed as a cause-and-effect structure (describing what sparked the protest and how it manifested itself). These superficial portrayals—as with most of mainstream media—failed to provide broader context or in-depth information. In truth, these protests are not caused by a single event, but by many events happening over time within the neighborhood.

Following my early analysis of news media, I scoured other publicly-available online sources, including social media, online blogs, and community groups. I began with the formerly identified actors: the protest organizers, specific leaders, and protesters. Scanning through their social media profiles, I found content not portrayed in any mainstream media.

In the case of the ReclaimRebuild Eglinton Protest in 2020, mainstream media centered around a short clip of a man acting erratically at the protest. On the Twitter account of Rebuild, Reclaim Eglinton, I found dozens of clips of hundreds of protesters marching down Eglinton—peacefully. They held signs, played music, and appeared extremely friendly. Mainstream media depicted this as a ‘violent’ protest where the reality was far from that. In each of these protests, I found enormous discrepancies in narratives. The narratives of protesters and the media (which often pushed messages by the Police) were completely different.

For each of the three events, I constructed a storyline. This was done by analyzing traditional media, resident accounts (both directly and indirectly, such as through social media), pictures, videos, etc. My stories do not present a definite or ‘correct story,’ but rather aim to provide deeper context to why these protests happened. For example, traditional media often attribute the 2015 BLM protest to the police murder of Andrew Loku, but fail to mention decades of racial discrimination in the community by police. The stories are much greater than what they are initially depicted as.

![]()

Figure 2. 3D Printed Model and Drawing of Protest Locations (Left to Right): Former York Memorial School, Oakwood LRT Station, and Eglinton West Station/Toronto Police 13 Division, 2023. Isaac Soares.

![]()

Traditionally, protests have occurred directly on Eglinton Ave West. People transform the busy street into a place of contestation. Unfortunately, not many places exist in the neighborhood for protests to happen - there are few public spaces for this to occur.

UNCOVERING PERSPECTIVES

In speaking to residents, I was often surprised by the diversity of answers and opinions presented to me. When I learned about the issues of gentrification in the neighborhood— both at school and in academic writings—it is often presented as a universally accepted problem and story. When I spoke to residents, I asked open-ended questions: What do you think of the neighborhood? What do you think of its changes? The answers surprised me.

One neighbor, a leader in the local Muslim community, was quite optimistic about the change. He acknowledged that the neighborhood was ‘getting fixed up and newer’ and saw growth in the neighborhood as a good thing. Conversely, another friend expressed nostalgia for the 1990s summers in Little Jamaica and a ‘spirit which no longer [existed].’ Still, others expressed relative neutrality to the idea of development and change. This sentiment—of perceived indifference—was both powerful and confusing, adding a grey area to an issue that was often black and white. The more people I spoke to, the more common themes I seemed to find in their opinions. Collectively, many acknowledged that the neighborhood was overdue for investment and change, wanting to see their neighborhood grow and flourish. They longed for change. At the same time, these people questioned whether they would fit into the new, changed neighborhood.

The Rebuild, Reclaim Little Jamaica protest, which took place in 2020, was a significant community demonstration specifically targeting gentrification and the lack of support for small businesses. Since then, there hasn’t been a protest focused on gentrification. My future design proposal aims to address this gap by creating a space for community groups to convene, organize, and stage demonstrations.

![]()

Figure 3. Depiction of Reclaim, Rebuild, Eglinton Protest at Oakwood and Eglinton Ave. Messages on signs were present in this protes, 2023. Isaac Soares.

I’m a Daniels design student with a background in Environmental Science, currently engaged in a project combating gentrification in Little Jamaica. My research spans various roles, from studying early modernist environmentalist architects under Prof. Hans Ibelings, to exploring local ecologies for a school competition in Prague, to investigating changes in Georgian townhomes in London. I run a freelance architectural practice, working on projects throughout the GTA, particularly in missing middle densification, such as laneway homes and multiunit residences. In my free time, I enjoy biking, camping, and traveling. One of my favorite activities is building models or anything hands-on, stemming from my interest in construction work during summers.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Rebuild, Reclaim Litte Jamaica March, Little Jamaica, August 29, 2020. Reclaim Eg West, 2023. Isaac Soares.

My thesis project focuses on transit-induced gentrification in Little Jamaica, also addressing issues of discrimination, disinvestment, and poor public services. In the first part of my project, I explore various protests and movements to understand the stories, actors, and events that led to these demonstrations. This provides a deeper understanding of the current and historical issues experienced. By speaking to residents and advocates, I construct stories based on resident accounts - which often differ from news media.

(DE)CONSTRUCTING NARRATIVES

The early stages of my research stemmed from mainstream media, through which I used different search filters—keywords, dates, and locations—to locate relevant publications. I read through these articles and took note of the organizations, protesters, and organizer names. (These figures would be important for conducting alternative research later on). After reading multiple articles on each of the three protests, I was able to identify many emerging patterns and similarities.

Mainstream news sources such as CP24, CBC, and the Toronto Star generally followed a similar narrative and included the same information. The stories were often constructed as a cause-and-effect structure (describing what sparked the protest and how it manifested itself). These superficial portrayals—as with most of mainstream media—failed to provide broader context or in-depth information. In truth, these protests are not caused by a single event, but by many events happening over time within the neighborhood.

Following my early analysis of news media, I scoured other publicly-available online sources, including social media, online blogs, and community groups. I began with the formerly identified actors: the protest organizers, specific leaders, and protesters. Scanning through their social media profiles, I found content not portrayed in any mainstream media.

“The narratives of protesters and the media (which often pushed messages by the Police) were completely different.”

In the case of the ReclaimRebuild Eglinton Protest in 2020, mainstream media centered around a short clip of a man acting erratically at the protest. On the Twitter account of Rebuild, Reclaim Eglinton, I found dozens of clips of hundreds of protesters marching down Eglinton—peacefully. They held signs, played music, and appeared extremely friendly. Mainstream media depicted this as a ‘violent’ protest where the reality was far from that. In each of these protests, I found enormous discrepancies in narratives. The narratives of protesters and the media (which often pushed messages by the Police) were completely different.

For each of the three events, I constructed a storyline. This was done by analyzing traditional media, resident accounts (both directly and indirectly, such as through social media), pictures, videos, etc. My stories do not present a definite or ‘correct story,’ but rather aim to provide deeper context to why these protests happened. For example, traditional media often attribute the 2015 BLM protest to the police murder of Andrew Loku, but fail to mention decades of racial discrimination in the community by police. The stories are much greater than what they are initially depicted as.

Figure 2. 3D Printed Model and Drawing of Protest Locations (Left to Right): Former York Memorial School, Oakwood LRT Station, and Eglinton West Station/Toronto Police 13 Division, 2023. Isaac Soares.

Traditionally, protests have occurred directly on Eglinton Ave West. People transform the busy street into a place of contestation. Unfortunately, not many places exist in the neighborhood for protests to happen - there are few public spaces for this to occur.

UNCOVERING PERSPECTIVES

In speaking to residents, I was often surprised by the diversity of answers and opinions presented to me. When I learned about the issues of gentrification in the neighborhood— both at school and in academic writings—it is often presented as a universally accepted problem and story. When I spoke to residents, I asked open-ended questions: What do you think of the neighborhood? What do you think of its changes? The answers surprised me.

“Collectively, many acknowledged that the neighborhood was overdue for investment and change, wanting to see their neighborhood grow and flourish. They longed for change. At the same time, these people questioned whether they would fit into the new, changed neighborhood.”

One neighbor, a leader in the local Muslim community, was quite optimistic about the change. He acknowledged that the neighborhood was ‘getting fixed up and newer’ and saw growth in the neighborhood as a good thing. Conversely, another friend expressed nostalgia for the 1990s summers in Little Jamaica and a ‘spirit which no longer [existed].’ Still, others expressed relative neutrality to the idea of development and change. This sentiment—of perceived indifference—was both powerful and confusing, adding a grey area to an issue that was often black and white. The more people I spoke to, the more common themes I seemed to find in their opinions. Collectively, many acknowledged that the neighborhood was overdue for investment and change, wanting to see their neighborhood grow and flourish. They longed for change. At the same time, these people questioned whether they would fit into the new, changed neighborhood.

The Rebuild, Reclaim Little Jamaica protest, which took place in 2020, was a significant community demonstration specifically targeting gentrification and the lack of support for small businesses. Since then, there hasn’t been a protest focused on gentrification. My future design proposal aims to address this gap by creating a space for community groups to convene, organize, and stage demonstrations.

Figure 3. Depiction of Reclaim, Rebuild, Eglinton Protest at Oakwood and Eglinton Ave. Messages on signs were present in this protes, 2023. Isaac Soares.