About Junk and Hanging Out

JANA RUMJANCEVA

I am at last becoming at home in Ontario, making peace with its sprawling distances and extreme weather, all made worthwhile by the people, their excitements and commitments. I spend my time making, drawing, and building, as well as constantly learning how to get better at all three.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Reworked Laundry Drum, 2023. Photos by Habib Yosufi.

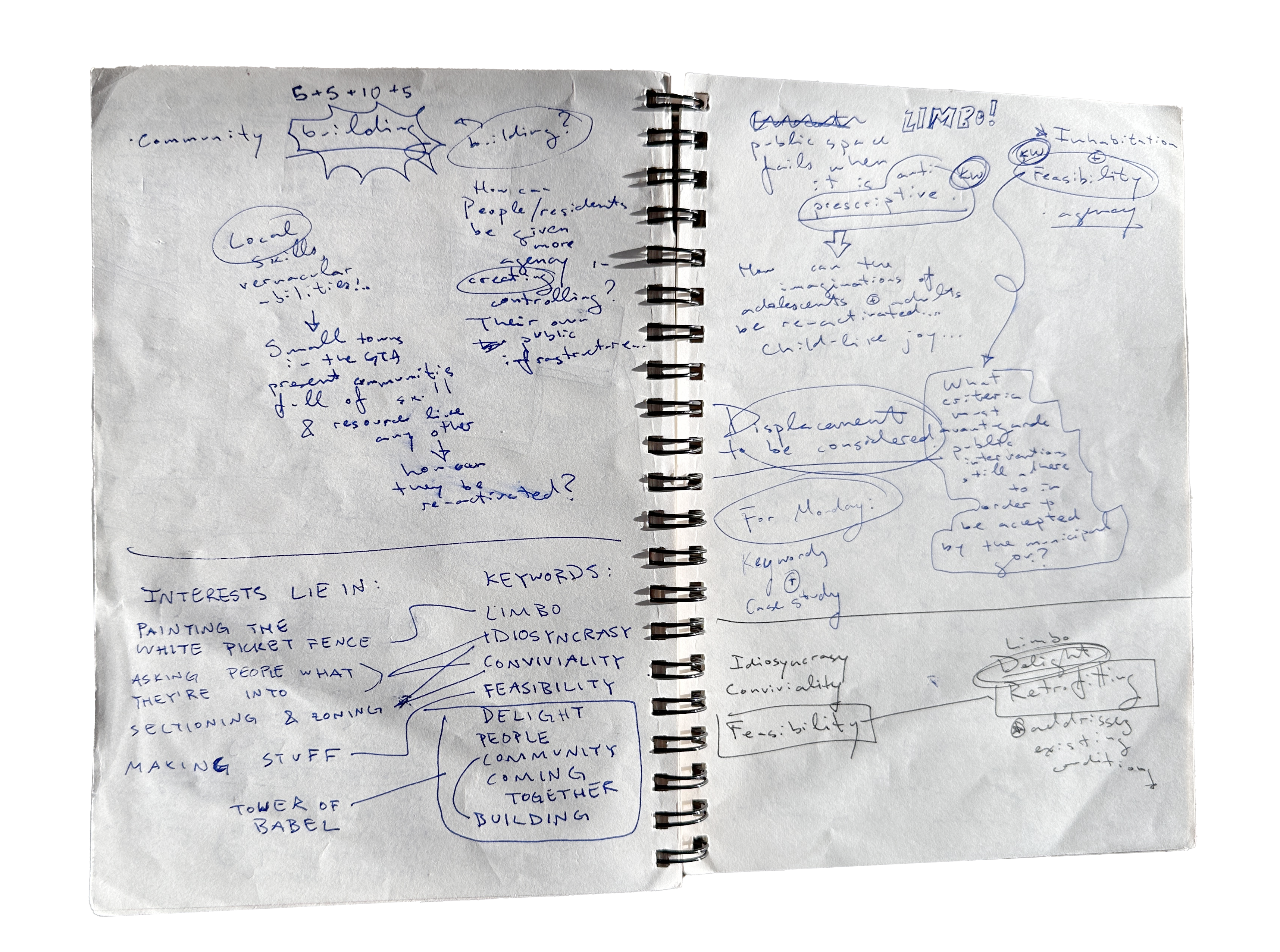

In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the BAAS Design Specialist, I have been working on a thesis project to present for review in April 2024. My thesis is about junk and hanging out. The project, year-long in the context of school—and, realistically, far more expansive than that—takes inspiration from the affinities for DIY and home renovation that I observed in suburbanites of the Greater Toronto Area. The project aims to harness these affinities into creation of public guerilla furniture and community organisation in the currently sterile and cookie cutter suburban public realm.

In their book, Degrowth in the Suburbs: A Radical Urban Imaginary, Samuel Alexander and Brendan Gleeson write on the need to reimagine the colonial North American and Australian suburban landscapes.[1] They state that it does not matter how realistic it is to do so: only that it is, without a doubt, necessary. The book quotes suburban catastrophists, such as James Kunstler, who argue that global fossil fuel depletion will turn the North American car-centric suburban fabric into urban wasteland, and subsequently argues that this does not necessarily have to be the case.[2] Suburban lifestyle, originally emblematic of success under capitalism, can be radically retrofitted.

“I invite the populations disillusioned with the suburban landscape to come together to re-imagine its physical realm: to build community in its most literal sense.”

This re-imagining of suburbia, its infrastructure, and any other similarly failing system, can and should be conceived via grass- roots organisation, rather than lament towards and aspiration for action from growth-fixated governments. As is put in Degrowth in the Suburbs, “This is not to deny the need for ‘top-down’ structural change. [The argument is] simply that the necessary action from governments will not arrive until there is an active culture of sufficiency that demands it.”[3] It is apparent that a paradigm shift is necessary, one where suburban towns are no longer considered appendages to the metropolis, and rather envisioned as thriving small towns and communities in their own right. This is only possible as long as the North American suburban lifestyle ceases to be synonymous with consumption.

As the driver for the aspirations of this project, I am interested in how people have long been able to come together over the making of things. The practice of coming together powers and sustains a revolutionary force, which can be used to push back upon the isolating nature of the stereotypical suburb that is beneficial to the status quo. I invite the populations disillusioned with the suburban landscape to come together to re-imagine its physical realm: to build community in its most literal sense.

THE PROJECT, REALLY

So. I am looking at failures of suburbia, and trying to address its realities of wastefulness and alienation. The work takes the shape of an optimistic take on design provocation and on the immediate agency of designers and citizens. I want to make things, and encourage others to make things as well.

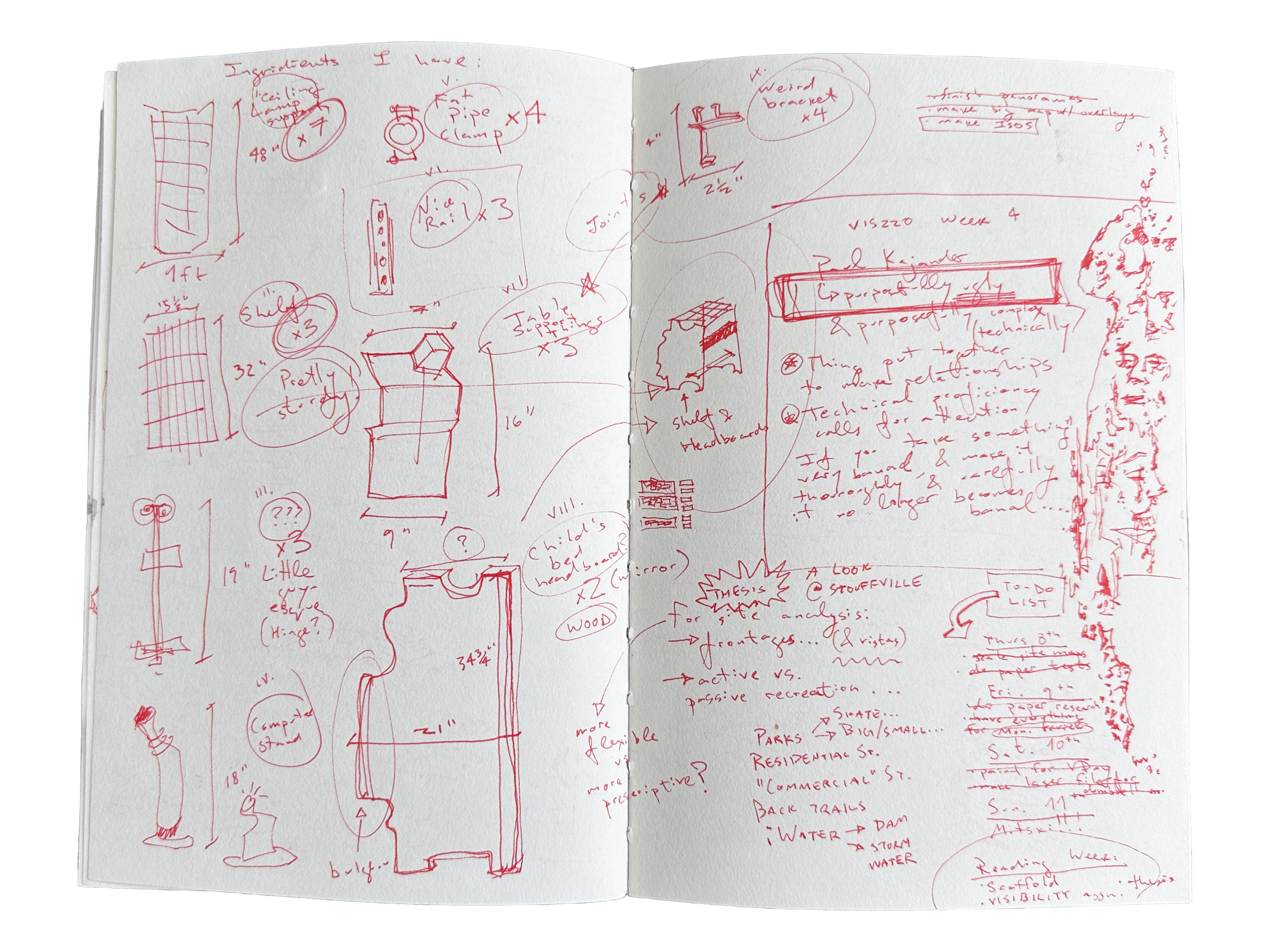

The thesis seeks to program the town of Stouffville, Ontario to produce its own vernacular architecture, using local resources and efforts - namely, using construction/home renovation junk. For the most part, we will be looking at construction of bespoke furniture out of discarded material. The artefacts to be produced for this project will be a manual (How to use junk/scavenged material? How to make things? What to make?), physical prototypes (What do these objects actually look like?), and a pavilion/workspace proposal (In Stouffville, where would people actually go to do this? Is this a new type of public space?).

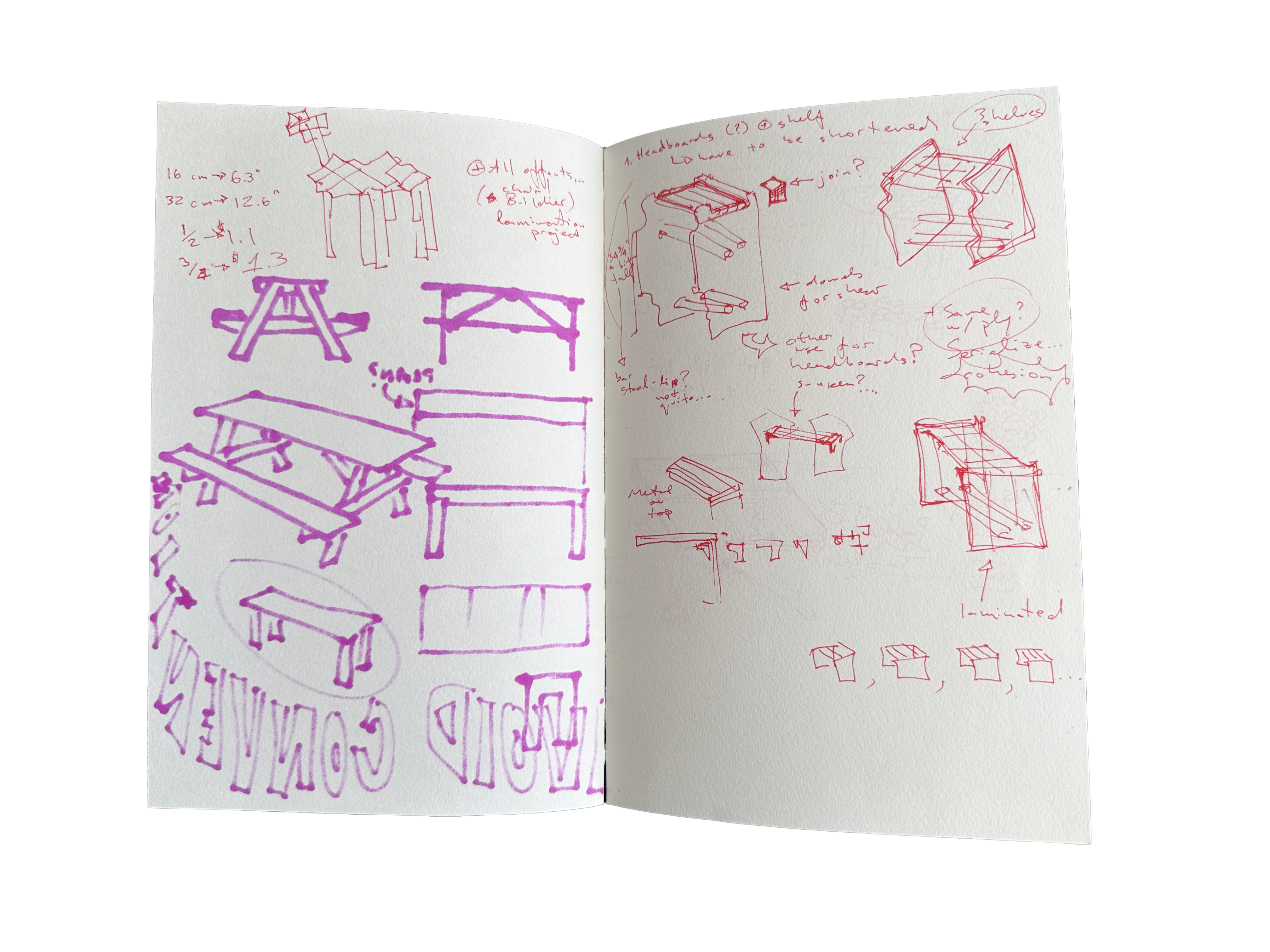

The manual, taking other DIY manuals as precedent, will describe urban furniture designs of varying construction difficulty, all relying on an inventory of typical household junk hoarded following suburban renovation projects. The proposed furniture designs would graft onto the existing condition of the suburb. The manual will take the form of a zine, to be distributed en masse. Following the systems I design for constructing with junk, I will build prototypes at a 1-1 scale using my own scavenged material.

Lastly, I will propose a public space typology, where people are able to come together over the act of building, instead of being confined to individual garage workshops. In such a space, tools could be provided and junk/construction material could be both stored and exchanged.

THE RESEARCH

I turn to my own suburban adolescence as an antecedent for this research, most of which was spent either at a friend’s house (private, repetitive, often imposing to your friend’s parents) or at a parking lot (public, even more repetitive, only possible after one of your friends obtains a driver’s licence). Discourse surrounding third spaces has entered the mainstream in the past decade, as public space rapidly declined in quality with the rise of corporate capitalism. The frustration of having nowhere to go in small-town North America is common: how do people find ways around this? For this project, primary research is integral, acting as the mode to reveal the existing needs and desires. I am developing and designing social programming as well, combining a social proposal with a physical one, as the production and installation of the physical interventions aims to potentially become a community-building event.

A quick glance at the town of Stouffville’s website reveals a decent effort put into events and programming (part of the reason for its selection as the site of choice) – this (typically social) programming will serve to ground and inspire proposed interventions to the physical infrastructure of the town. I am drawn to the successes and the joys. Working in architecture/design school, we begin large projects by collecting precedents. Most likely, this thing I want to do has been done before, and people a lot smarter and cooler have put better words to these thoughts.

The roots for this project’s interest in suburban public space grow from the booths on Stouffville GO platforms. Anyone who has taken a GO train is likely familiar with the booths on the train platforms, which are equipped with heat lamps, and are therefore occupiable public infrastructure in the winter months. One January evening, I was struck to see teenagers hanging out in one of the booths. They were not waiting for the train – they were passing the night in each other’s company at one of the only spaces where public furniture has been made accessible and remained inviting in the winter.

A heat lamp controlled by a switch with a timer in a covered booth is an extraordinarily simple move. I am interested in the booths as an existing point of interest for the population of the town, and the tension between them existing on private property, with the intention to be occupied briefly. How often do those teenagers hang out there? Are they ever persecuted for it? Is it possible to make such a space – privately owned public space, appropriate for the winter months – intentional?

So. I am looking at failures of suburbia, and trying to address its realities of wastefulness and alienation. The work takes the shape of an optimistic take on design provocation and on the immediate agency of designers and citizens. I want to make things, and encourage others to make things as well.

The thesis seeks to program the town of Stouffville, Ontario to produce its own vernacular architecture, using local resources and efforts - namely, using construction/home renovation junk. For the most part, we will be looking at construction of bespoke furniture out of discarded material. The artefacts to be produced for this project will be a manual (How to use junk/scavenged material? How to make things? What to make?), physical prototypes (What do these objects actually look like?), and a pavilion/workspace proposal (In Stouffville, where would people actually go to do this? Is this a new type of public space?).

The manual, taking other DIY manuals as precedent, will describe urban furniture designs of varying construction difficulty, all relying on an inventory of typical household junk hoarded following suburban renovation projects. The proposed furniture designs would graft onto the existing condition of the suburb. The manual will take the form of a zine, to be distributed en masse. Following the systems I design for constructing with junk, I will build prototypes at a 1-1 scale using my own scavenged material.

Lastly, I will propose a public space typology, where people are able to come together over the act of building, instead of being confined to individual garage workshops. In such a space, tools could be provided and junk/construction material could be both stored and exchanged.

THE RESEARCH

I turn to my own suburban adolescence as an antecedent for this research, most of which was spent either at a friend’s house (private, repetitive, often imposing to your friend’s parents) or at a parking lot (public, even more repetitive, only possible after one of your friends obtains a driver’s licence). Discourse surrounding third spaces has entered the mainstream in the past decade, as public space rapidly declined in quality with the rise of corporate capitalism. The frustration of having nowhere to go in small-town North America is common: how do people find ways around this? For this project, primary research is integral, acting as the mode to reveal the existing needs and desires. I am developing and designing social programming as well, combining a social proposal with a physical one, as the production and installation of the physical interventions aims to potentially become a community-building event.

A quick glance at the town of Stouffville’s website reveals a decent effort put into events and programming (part of the reason for its selection as the site of choice) – this (typically social) programming will serve to ground and inspire proposed interventions to the physical infrastructure of the town. I am drawn to the successes and the joys. Working in architecture/design school, we begin large projects by collecting precedents. Most likely, this thing I want to do has been done before, and people a lot smarter and cooler have put better words to these thoughts.

The roots for this project’s interest in suburban public space grow from the booths on Stouffville GO platforms. Anyone who has taken a GO train is likely familiar with the booths on the train platforms, which are equipped with heat lamps, and are therefore occupiable public infrastructure in the winter months. One January evening, I was struck to see teenagers hanging out in one of the booths. They were not waiting for the train – they were passing the night in each other’s company at one of the only spaces where public furniture has been made accessible and remained inviting in the winter.

A heat lamp controlled by a switch with a timer in a covered booth is an extraordinarily simple move. I am interested in the booths as an existing point of interest for the population of the town, and the tension between them existing on private property, with the intention to be occupied briefly. How often do those teenagers hang out there? Are they ever persecuted for it? Is it possible to make such a space – privately owned public space, appropriate for the winter months – intentional?

“As architects, it is of utmost importance to understand how things are built, and to actually get our hands dirty building them.”

Lastly, and most importantly, this project is interested in analog forms of making as a mode of research. This one is perhaps a bit obvious, as I am dealing with both bespoke furniture and found materials, and both require hands-on work. I find hand drawing and building integral to my processes, and the latter in particular constantly relevant to my position in the discussions of architectural and industrial design. Throughout my experience of the architectural profession, I found the disassociation between the designer, the engineer, and the contractor jarring. As architects, it is of utmost importance to understand how things are built, and to actually get our hands dirty building them. It is quite hard to understand the realities of built form while exclusively looking at it in Rhino. Other than being integral to the creation of anything, having knowledge of and practice in low-tech manners of making things is also simply fun. I enjoy when my labour manifests in the physical, as something to hold in my hands; this project specifically started out of a desire to make.

DRUM BEGINNINGS

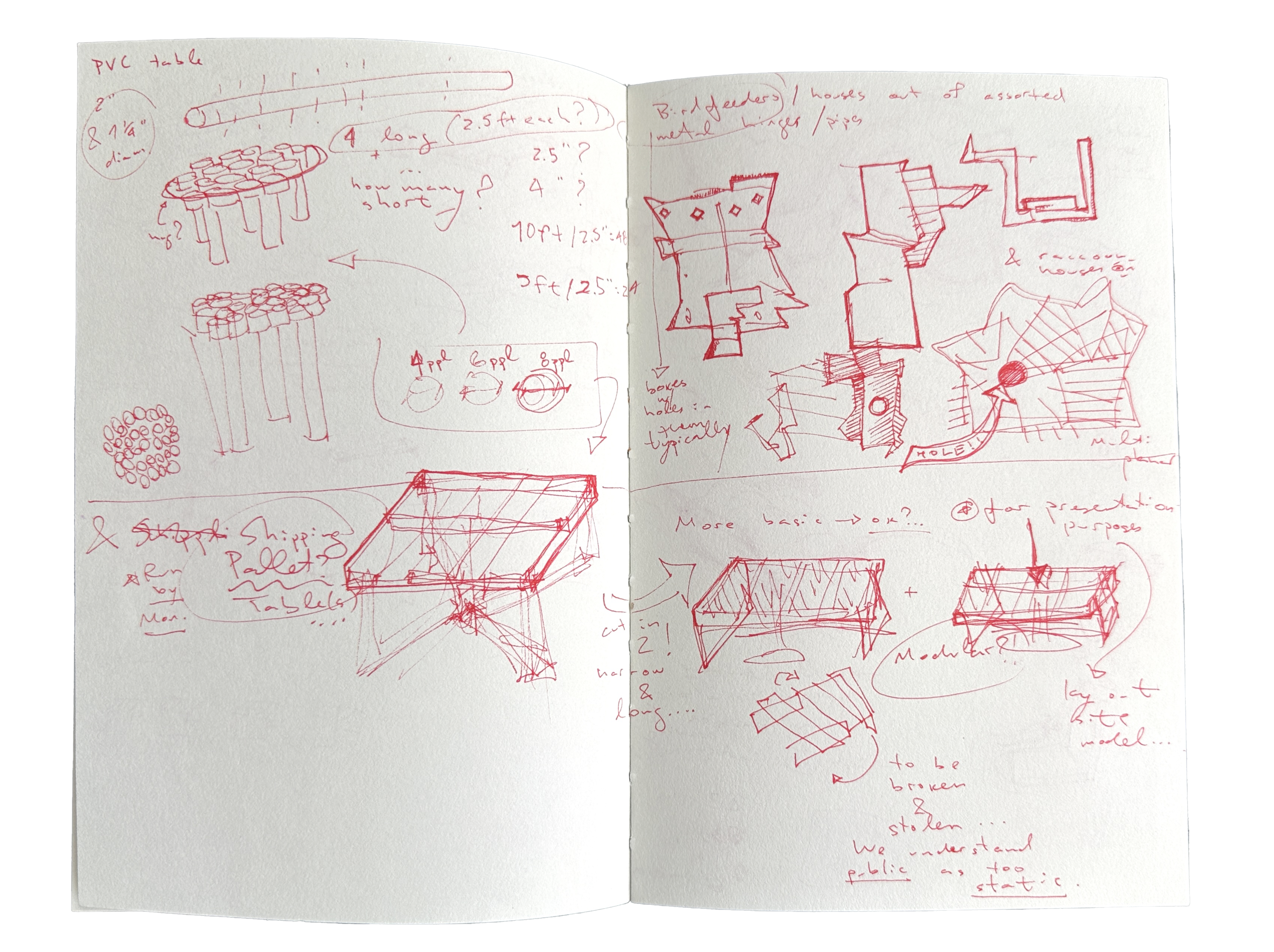

A precedent I looked extensively at were junk playgrounds. These are playgrounds that involve “loose parts”: leftover construction material, natural resources, and found objects. The ethos behind the playgrounds lies in allowing children unrestricted play, as well as access to build and create whatever they desire, and are typically temporary alternative play spaces found all over the world. Research on junk playgrounds was what got me trying to build a prototype for an urban furniture piece/part of a playground using household junk. To begin with, I used some leftover plywood from my parents’ renovation project and a laundry drum from when the dryer broke down.

Loosely inspired by junk playgrounds, I began concentrating on upcycling. Beyond the obvious challenges of building with scavenged material (such as the uniqueness of the pieces and their resistance to standardisation), my considerations have to ensure that occupiable junk remains a feasible and inviting proposal. These designs can only really be considered successful if they are built and used.

The reality of this project is that it demands the constant physical making of things/prototypes, which was intentional in its conception. This mode of research is perhaps best documented by the sketches scribbled while talking through an idea, and timelapses of work. I adore watching timelapses of people building things – I suspect many of us do as well, if view counts on those viral woodworking or glassblowing Instagram accounts are any true indicator. It is satisfying to see a thing come together: I have been pointedly interested in documenting my construction processes as much as the final product itself. Most specifically, I find videos and/or photos of myself and other bodies at work to be some of the most substantial deliverables of any project. When the processes of physical labour become elevated to the same level as the final form, something important happens.

MANUAL

The construction of the drum proved the need to come up with certain sets of rules that would alleviate the burdens of constructing with scavenged, non-standard dimensional materials. I began putting together the manual, with typical heights/depths/lengths of tables and benches, as well as typical body measurements for bespoke construction. I am still unsure about this part, but I think the actual manual will consist of a quick overview of construction methods, materials, and examples of junk, as well as “examples” of unconventional public furniture to be built: my prototypes.

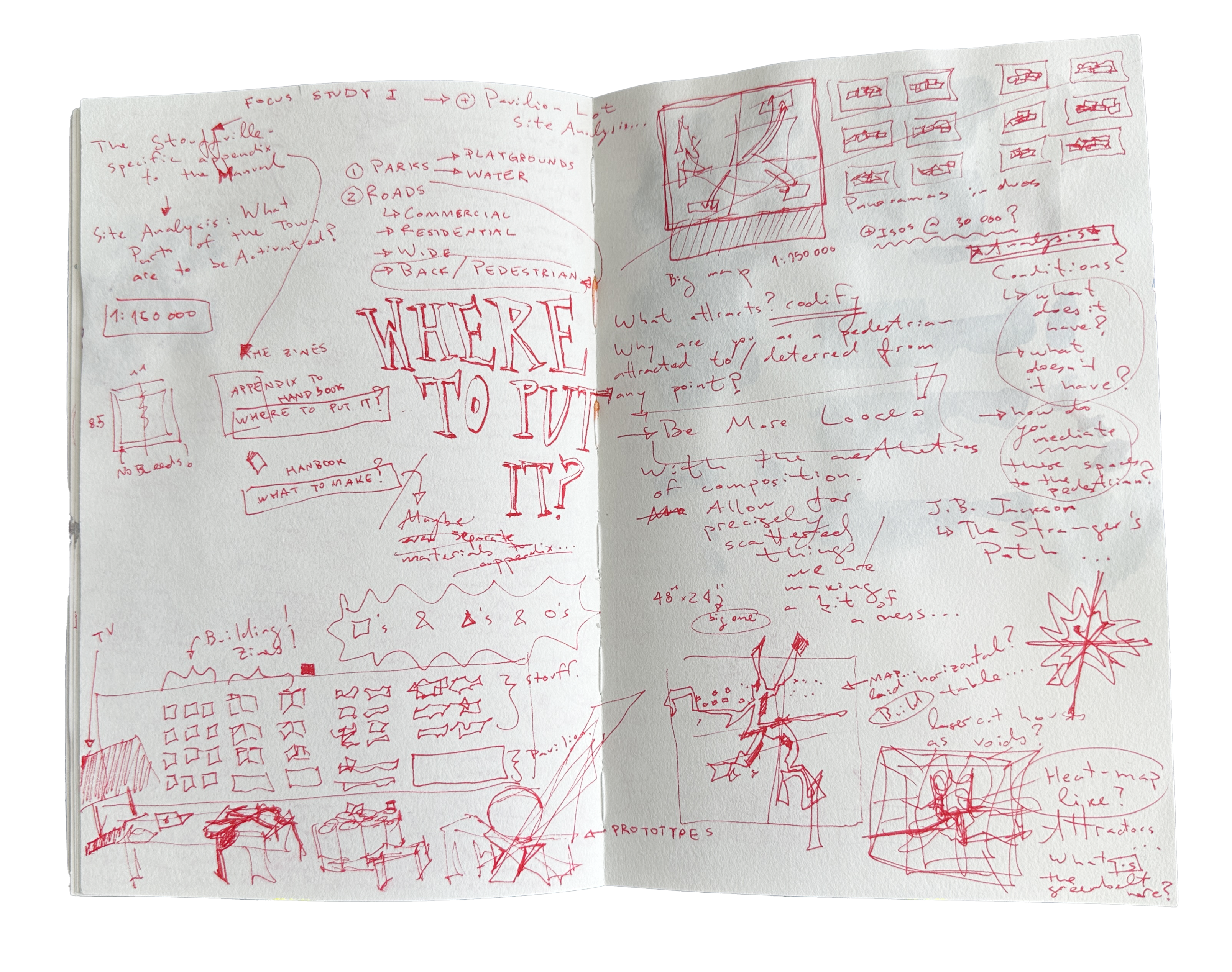

WHILE TIRED: SITE ANALYSIS

When working on large scale projects, I prefer sectioning them off into little projects to do in parallel. Not only because work undertaken at the same time can provide context and inform the project further, but also because that is how I, personally, attempt to mitigate burnout. When stuck on or tired of one thing, it is helpful to switch gears and work on something completely different, even if within the context of the same project.

I have been putting together drawings and photo collages of Stouffville, ON, in tandem with working on the manual. Taking walks around the town grounds me in the realities within which I am working. My site analysis efforts will also be useful once I begin work on the last aspect of my project, the pavilion. As a treat for getting to the end, and for the sake of total transparency, I must confess that site analysis for this project is just kind of hanging out around my parents’ home. It is a thesis project, after all, and those tend to be quite personal.

My parents bought a suburban home in Stouffville eight years after immigrating to Canada, and have been homeowners for almost three years now. Stouffville is found on the peripheral border of the GTA, 50 kilometres north of downtown Toronto, with a population of just under 50 000 in 2021. I spent most of my adolescence in Vaughan, Aurora, and Newmarket, and went to high school in Richmond Hill. All of the four towns listed share a similar sprawled atmosphere, are outrageously car-centric and disinterested in individuality, allowing for the ease with which residents may typically move (float, drive) throughout the monotonous GTA. These areas are identity-less, an in-between zone laying between the downtown core and the more picturesque, rural Northern Ontario.

My parents are both software developers, and I have never seen them work much with their hands, let alone take on extensive construction or landscaping projects. Prior to the move to Stouffville, that is. Since moving into a place that was theirs, they begun to engage in a seemingly never-ending stream of renovation projects, ranging from fixing the drainage in the backyard and installing plywood floors in place of ripped-up carpet, to designing custom furniture for the living room. This newfound interest is both their personal post-quarantine desire to “try something new,” and a commonly observed side-effect of home ownership. I bear constant witness to the roof amendments, or interlock installations, or new deck construction projects that exist in the neighbourhood. It is important to note that, in Stouffville at least, the labour is rarely outsourced, and is commonly done by the residents themselves. In the summer, when people leave their garage door open, virtually every other house boasts its own small workshop, at the very least equipped with a chop saw and tons of left-over material from past projects.

For the design project to cater to existing realities as opposed to its own self-indulgence agrees with the work I hope to produce; my proposals will strive to be feasible both in terms of construction and implementation. But beyond bureaucracy, feasibility is also interested in the existing interests and abilities of the residents. The existing efforts of Stouffville are to be considered as precedent, and are to be elaborated upon.

I will also say that, sometimes, site analysis is just an excuse to get out there. I have never once been able to come up with a design while staring at a screen. Ideas come while moving and looking at things attentively, and also while daydreaming and spacing out.

Figure 3. Stouffville Panoramas, 2023. Jana Rumjanceva.

1. Samuel Alexander and Brendan J. Gleeson, Degrowth in the Suburbs: A Radical Urban Imaginary (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) 2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.