The Making of Mas: Archiving Toronto’s Caribana

JASMINE SYKES

Throughout my architectural studies, I found it essential to address the lack of diversity within the field as I navigated through the discipline as a Black woman. Being of African and Caribbean descent, the absence of Black representation was something I could not overlook. In both my academic and professional pursuits, I have always sought opportunities to uplift and emphasize the Black community in architecture.

I completed my undergraduate degree in Architectural Studies with a minor in Urbanism at Carleton University and recently earned my Master of Architecture at the University of Toronto. My academic journey has fuelled my passion for exploring the intersection of architecture, culture, diversity, and social equity.

This intersectionality inspired my most recent work, my thesis on Toronto’s Caribana, an event of great significance to the Caribbean diaspora in Toronto. In this thesis, I reveal the spatial agency of the celebration and in a way have been able to place the Black community at the forefront of architecture—a space we don’t often have the opportunity to occupy. I see my work as a celebration and affirmation of Black presence and influence in the architectural realm.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

Figure 1. Crowd walking along Caribana, Notting Hill, London ca. 1970-1980. Jasmine’s father.

This year marks the 56th anniversary of Caribana, which was originally supposed to be a one-off event, put together by a group of West Indians for Expo 67’ who wanted to share the beauties of West Indian culture with the City of Toronto. Today, Caribana is the largest cultural festival in North America, bringing in over two million people each year; however, many individuals who have grown up alongside the production of Caribana have witnessed the transformation of the event over the years.

On August 4th, 2023, an article titled “The History and Legacy of Caribana Must Be Preserved” by scholar and writer Camille Hernández-Ramdwar, was published in the Globe and Mail.[1] The article vocalizes the growing concerns over the loss of the parade’s connection to Caribbean roots alongside the lack of archival efforts and documentation of the celebration over the last five decades. As discussions regarding the lack of archival efforts and scholarly attention toward Caribana’s history have gained momentum, my thesis endeavors to bridge this gap by advocating for the preservation and deeper understanding of Caribana’s legacy within Toronto’s cultural milieu.

100X EXTRACTIONS

![]()

Figure 2. Diagram depicting some of the extractions, 2023. Jasmine Sykes.

THE ACT OF (INFORMAL) ARCHIVING

It was important to me to first understand my connection to the festival before diving into the starting stages of creating an archive that is long overdue. In doing so, I hoped to address the need to capture, collect, and consolidate the histories and memories that Caribana has brought to our city. The act of archiving itself carries power as the author of the archive holds the power in deciding what stories, images, and histories are preserved. As I began to approach the absence of archival efforts surrounding Caribana, I began to think about the power that I held–just from the act of trying to create this archive.

When thinking of the traditional way of archiving, the power of the archive is held in the hands of states of authority as they decide whether the collection of documents ‘fits’ or ‘suits’ the conditions of their archive. It is in the context of this history that my innate reaction was to reject this traditional form of archiving. I believe the power of this archive for Caribana lies in the premise that one scholar or author does not get to decide whether something best ‘fits’ or ‘suits’ the archive.

This archive for Caribana is meant to be a collection that uplifts the various stories, voices, and experiences of those who have taken part. Every one of these voices is worth listening to. It is with this in mind that I began to consider informal ways of archiving. The formation of informal archives allows individuals whose stories are not usually produced in formal archives to be heard. In many instances, the majority of these stories that go unheard or undocumented are from individuals or groups from minorities or marginalized peoples. Through the act of informal archiving, I wanted to reveal the voices that have remained unheard for so long: the voices of groups and individuals involved with the formation of Caribana.

![]()

![]()

Figure 3. Creating Borders, 2023. Jasmine Sykes.

56X YEARS, 56X BOOKS

Embarking on the journey of archiving Caribana, I felt that the first step was to learn about its rich history–a history that has spanned over 56 years in Toronto. My initial excitement to learn about its history was quickly confronted by a challenge, as I began to realize how limited the available information was on the event. As I searched the internet, I was constantly met with dead ends. In addition, I knew that my interest in finding the costs and financial contributions of the parade to the city would also pose a great challenge. It was in this void of data and information that I realized what my first step in this archive needed to be, and that was to weave together the re-telling of Caribana’s history and make it accessible for those who also want to understand its legacy. Throughout the semester I traversed countless personal blogs, news articles, and publications, piecing together the story of Caribana’s past. What had begun as a simple inquiry turned into the creation of 56 books that revealed the beautiful retelling of this cultural event. These books pieced together the diverse voices scattered across the digital landscape.

As I began to compile these 56 books, I began to think about the differential experiences of reading about and seeing the festival. Although one can read and learn about Caribana’s history, to see it is a whole other experience. Caribana itself is not only a beautiful story to hear but a spectacle to see. This thought came to me when I was visiting an existing archive at York University left behind by a Caribana founder, Kenneth Shah Fonds. The collection contained more than I could have imagined: on top of the notes, letters, and documents outlining the events of Caribana, I was overwhelmed by the images, drawings, and maps that were preserved. In engaging with this archive, I knew that these stories re-telling each year’s events needed to be met with a visual history, this visual history consisting of various photographs, newspaper clippings, videos, and drawings found. The 56 books expanded to provide both a written and visual retelling of Caribana.

Soon after compiling these books, I realized that my way of archiving had become a barrier as I began to think about access. Who will have access to these books? How will these books be shared? How can people add their images and experiences to these books? It was through these questions that I began to reconsider the media through which I was archiving Caribana. After careful consideration and exploration, the idea of housing the archive digitally crossed my mind. By presenting these books in the form of a website, I’ve not only been able to make this information accessible, but I am also able to address the aforementioned problem of individual authorship.

By housing these books within a website, I’ve also been able to foster an open forum for individuals to share their images, videos, and experiences. The archive is then able to transcend past its static form and instead has become something dynamic that is constantly welcoming contributions, the act of archiving in a sense becoming endless. The making of this archive for Caribana remains an ongoing journey, and one that I hope continues to evolve and grow. I hope that this archive will successfully portray the vibrant legacy that is Caribana as well as help foster the ongoing sharing and documenting of this festival for generations to come.

Throughout my architectural studies, I found it essential to address the lack of diversity within the field as I navigated through the discipline as a Black woman. Being of African and Caribbean descent, the absence of Black representation was something I could not overlook. In both my academic and professional pursuits, I have always sought opportunities to uplift and emphasize the Black community in architecture.

I completed my undergraduate degree in Architectural Studies with a minor in Urbanism at Carleton University and recently earned my Master of Architecture at the University of Toronto. My academic journey has fuelled my passion for exploring the intersection of architecture, culture, diversity, and social equity.

This intersectionality inspired my most recent work, my thesis on Toronto’s Caribana, an event of great significance to the Caribbean diaspora in Toronto. In this thesis, I reveal the spatial agency of the celebration and in a way have been able to place the Black community at the forefront of architecture—a space we don’t often have the opportunity to occupy. I see my work as a celebration and affirmation of Black presence and influence in the architectural realm.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Crowd walking along Caribana, Notting Hill, London ca. 1970-1980. Jasmine’s father.

This year marks the 56th anniversary of Caribana, which was originally supposed to be a one-off event, put together by a group of West Indians for Expo 67’ who wanted to share the beauties of West Indian culture with the City of Toronto. Today, Caribana is the largest cultural festival in North America, bringing in over two million people each year; however, many individuals who have grown up alongside the production of Caribana have witnessed the transformation of the event over the years.

On August 4th, 2023, an article titled “The History and Legacy of Caribana Must Be Preserved” by scholar and writer Camille Hernández-Ramdwar, was published in the Globe and Mail.[1] The article vocalizes the growing concerns over the loss of the parade’s connection to Caribbean roots alongside the lack of archival efforts and documentation of the celebration over the last five decades. As discussions regarding the lack of archival efforts and scholarly attention toward Caribana’s history have gained momentum, my thesis endeavors to bridge this gap by advocating for the preservation and deeper understanding of Caribana’s legacy within Toronto’s cultural milieu.

100X EXTRACTIONS

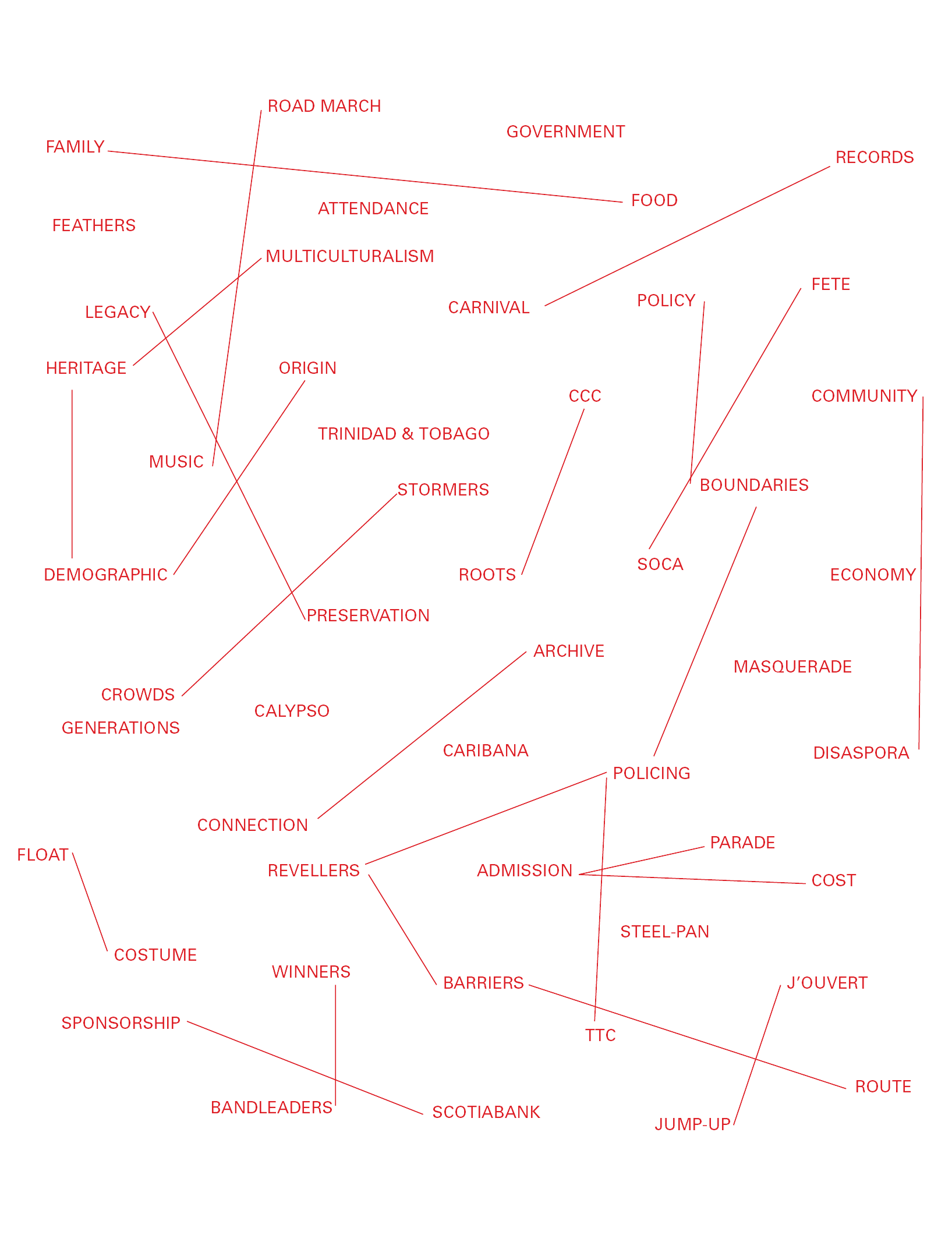

Figure 2. Diagram depicting some of the extractions, 2023. Jasmine Sykes.

Embarking on this journey to bridge this gap on the lack of preservation and knowledge on the legacy of Caribana was both challenging and deeply rewarding. At the forefront of this endeavor was the goal of amplifying the voices and stories of all those who have contributed to this vibrant celebration. My own part in this narrative soon dawned on me, having grown up amidst the pulsating rhythms of Soca and Calypso, proudly waving a Grenadian flag. Thus, my endeavors commenced with a reflection on the essence of Caribana from my perspective: the words, the elements, and the many experiences it embodies. This took the form of 100 terms, or as I have called them, 100 extractions. To initiate the process of conveying the essence of Caribana to my peers, I distilled my associations with the festival into a collection of 100 terms.

I selected a few of these words for deeper exploration. Through this process, I revealed the intricate elements that make up the festival’s rich history. An example of one of the words from my extraction was ‘boundaries’.

This word carries significance as the boundaries for me, and for many others, have transformed our relationship and experience with Caribana. From 1967 to 1990 the Caribana parade took place along the streets of Toronto, the only boundary between people viewing the parade and those taking part in the parade being a couple of steps in one direction. However, as the parade grew, its route moved and in 1991 the parade would now take place along Lakeshore Boulevard. Along with this route change came a change in boundaries as festival organizers deployed eight-foot tall fences to separate viewers from those taking part in the parade.

Throughout the years the festival faced issues with viewers—or as we refer to them, stormers—interfering with those who have paid to partake in the parade. The evolution of these boundaries carries great importance when considering the evolution of the festival.

I selected a few of these words for deeper exploration. Through this process, I revealed the intricate elements that make up the festival’s rich history. An example of one of the words from my extraction was ‘boundaries’.

This word carries significance as the boundaries for me, and for many others, have transformed our relationship and experience with Caribana. From 1967 to 1990 the Caribana parade took place along the streets of Toronto, the only boundary between people viewing the parade and those taking part in the parade being a couple of steps in one direction. However, as the parade grew, its route moved and in 1991 the parade would now take place along Lakeshore Boulevard. Along with this route change came a change in boundaries as festival organizers deployed eight-foot tall fences to separate viewers from those taking part in the parade.

Throughout the years the festival faced issues with viewers—or as we refer to them, stormers—interfering with those who have paid to partake in the parade. The evolution of these boundaries carries great importance when considering the evolution of the festival.

THE ACT OF (INFORMAL) ARCHIVING

It was important to me to first understand my connection to the festival before diving into the starting stages of creating an archive that is long overdue. In doing so, I hoped to address the need to capture, collect, and consolidate the histories and memories that Caribana has brought to our city. The act of archiving itself carries power as the author of the archive holds the power in deciding what stories, images, and histories are preserved. As I began to approach the absence of archival efforts surrounding Caribana, I began to think about the power that I held–just from the act of trying to create this archive.

When thinking of the traditional way of archiving, the power of the archive is held in the hands of states of authority as they decide whether the collection of documents ‘fits’ or ‘suits’ the conditions of their archive. It is in the context of this history that my innate reaction was to reject this traditional form of archiving. I believe the power of this archive for Caribana lies in the premise that one scholar or author does not get to decide whether something best ‘fits’ or ‘suits’ the archive.

This archive for Caribana is meant to be a collection that uplifts the various stories, voices, and experiences of those who have taken part. Every one of these voices is worth listening to. It is with this in mind that I began to consider informal ways of archiving. The formation of informal archives allows individuals whose stories are not usually produced in formal archives to be heard. In many instances, the majority of these stories that go unheard or undocumented are from individuals or groups from minorities or marginalized peoples. Through the act of informal archiving, I wanted to reveal the voices that have remained unheard for so long: the voices of groups and individuals involved with the formation of Caribana.

Figure 3. Creating Borders, 2023. Jasmine Sykes.

56X YEARS, 56X BOOKS

Embarking on the journey of archiving Caribana, I felt that the first step was to learn about its rich history–a history that has spanned over 56 years in Toronto. My initial excitement to learn about its history was quickly confronted by a challenge, as I began to realize how limited the available information was on the event. As I searched the internet, I was constantly met with dead ends. In addition, I knew that my interest in finding the costs and financial contributions of the parade to the city would also pose a great challenge. It was in this void of data and information that I realized what my first step in this archive needed to be, and that was to weave together the re-telling of Caribana’s history and make it accessible for those who also want to understand its legacy. Throughout the semester I traversed countless personal blogs, news articles, and publications, piecing together the story of Caribana’s past. What had begun as a simple inquiry turned into the creation of 56 books that revealed the beautiful retelling of this cultural event. These books pieced together the diverse voices scattered across the digital landscape.

As I began to compile these 56 books, I began to think about the differential experiences of reading about and seeing the festival. Although one can read and learn about Caribana’s history, to see it is a whole other experience. Caribana itself is not only a beautiful story to hear but a spectacle to see. This thought came to me when I was visiting an existing archive at York University left behind by a Caribana founder, Kenneth Shah Fonds. The collection contained more than I could have imagined: on top of the notes, letters, and documents outlining the events of Caribana, I was overwhelmed by the images, drawings, and maps that were preserved. In engaging with this archive, I knew that these stories re-telling each year’s events needed to be met with a visual history, this visual history consisting of various photographs, newspaper clippings, videos, and drawings found. The 56 books expanded to provide both a written and visual retelling of Caribana.

Soon after compiling these books, I realized that my way of archiving had become a barrier as I began to think about access. Who will have access to these books? How will these books be shared? How can people add their images and experiences to these books? It was through these questions that I began to reconsider the media through which I was archiving Caribana. After careful consideration and exploration, the idea of housing the archive digitally crossed my mind. By presenting these books in the form of a website, I’ve not only been able to make this information accessible, but I am also able to address the aforementioned problem of individual authorship.

By housing these books within a website, I’ve also been able to foster an open forum for individuals to share their images, videos, and experiences. The archive is then able to transcend past its static form and instead has become something dynamic that is constantly welcoming contributions, the act of archiving in a sense becoming endless. The making of this archive for Caribana remains an ongoing journey, and one that I hope continues to evolve and grow. I hope that this archive will successfully portray the vibrant legacy that is Caribana as well as help foster the ongoing sharing and documenting of this festival for generations to come.

1. Camille Hernandez-Ramdwar, “Opinion: The History and Legacy of Caribana Must Be Preserved,” The Globe and Mail, August 4, 2023.