An Archive of Memories, Washed Away

LIANE WERDINA

I am interested in design and its socio-political implications, which are closely related to a wider urban setting. My research focuses on how space can be carved to accommodate social and cultural activities as well as how spatial form can contribute to societal frameworks. As a designer, I am interested in how we can use our tools and knowledge of space, design and aesthetics to help dissect and analyze the built environment. I am concerned with the social responsibility of the built environment and how architects and designers contribute to creating meaningful and equitable environments.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

Figure 1. Conceptual recreation of Kurdish Pavilion structures, Toronto, 2023. Liane Werdina.

Objects of progress have often buried within them the story of a sacrificed history deemed less valuable. Thus, the act of preservation is a political decision that identifies what history is essential enough to be told - and which can be washed away to make room for progress. This research decodes how the Turkish government’s weaponization of water has been politicized and used to wash away Indigenous Kurdish culture, history, and future existence for Turkish progress. It addresses how the archival and antiquation of select histories is used to ensure an erasure of a Kurdish future. The project uses methods of subverting power projecting curatorial practices, such as world expositions, to protest the Turkish government’s actions and demand autonomy and acknowledgment of Kurdish people and their lost history and future. The research attempts to decenter these notions of progress by counter-archiving what is lost to make room for these objects of progress. Through subversion of hegemonic claims to innocence in the name of progress and environmental development, the aim of the project is to shed a light of truth onto the drowning of Indigenous built history, language, and agriculture as an act of cultural genocide.

CASE STUDY: THE TURKISH ILISU DAM AND DESTRUCTION OF HASANKEYF, KURDISTAN

The culmination of this research analyzes and critiques the Turkish government’s annexation of the Kurdish people of Hasankeyf, through the construction of hydro-infrastructure that in turn is instrumentalized to wash away their land and history. The creation of this infrastructure can be outlined as an act of spatial violence enacted on the Indigenous Kurds of Hasankeyf as a form of cultural genocide. Its ability to displace Indigenous Kurdish communities through the physical washing of archaeological sites, the sinking of monuments, and the loss of livelihoods has consequently been masked in the name of Turkish progress. The organized displacement of these people has been announced as an act of preservation of their history, through the displacement of housing, businesses, monuments and cemeteries.

This research highlights the Turkish government’s violence against the Kurdish people through the creation of this dam and the forced relocation of these people. It addresses this act of displacement as a form of violence rather than preservation, through the removal of locality and history from the land in which it belongs. This then addresses the erasure of physical space, and how it is used as a tool by hegemonic states to disassemble the non-physical histories and memories of the cultures that once inhabited them. The goal of the thesis is to explore methods to counter-colonial narratives of history and find spatial and visual representations of nationhood for those without a state, through the subversion of colonial practices of progress in hopes to disassemble the imperial violences found within them.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY: COUNTERING COLONIAL TECHNIQUES OF PROGRESS

The following research study contributes to the greater discourse on countering colonial methods of documentation in an attempt to subvert narratives of progress and historical preservation that are often at the expense of Indigenous narratives. Colonial and imperial powers have used the occupation of empty land to distort its history in the name of progress. However, objects of progress have often buried within them the story of a sacrificed history deemed less valuable in order to exploit, extract and claim natural resources. Contrary to the imaginary, these lands are not arid, nor are they “undeveloped” and “ancient”. They contain active presents and futures and the act of antiquating them to make room for colonial notions of progress is threatening to their existence. Thus, the act of preservation is a political decision that identifies what history is essential enough to be told—and which can be washed away to make room for progress.

Nations utilize spatial displays and collections of history such as museums, archives, and world expos as methods of ethnic cleansing hiding behind notions of progress and enlightenment. These formal displays often silence and disclude the voices of the stateless nations that have sacrificed their own history for said progress. Often, in order for stateless nations to achieve or advocate for autonomy and acknowledgment, they must find alternative routes of communication to amplify their voice.

This research explores how to counter this form of history-telling. Through imitation and mimicry of colonial practices of progress such as the archive, the museum and world expositions, nations can begin to construct an anti-colonial resistance method that highlights and exposes the problems with these methods of displaying history—one that is constructed and curated.1

There is a long history of Indigenous or oppressed minority nations utilizing languages of their hegemonic, controlling nations in order to communicate their existence. Within the research project, mimicry is used as an act of anti-colonial resistance to represent and bring voice to the colonized other. It is used to preserve Indigenous identities, whilst discounting the colonial subject’s claims to progress through mockery. The curatorial practice of collection within colonial museum techniques, influenced by anthropological theory, has supported the notion that Indigenous people, artifacts and cultures would be extinct—through death or assimilation —and needed to be documented as a part of a historical past and preserved through objects.2 In an act of protest, and communicating in the formalized colonial languages that oppress them, these communities are able to amplify their voices, announce their presence, and reclaim their narratives that are often stolen within these frameworks.

Archives, museums and expositions have been long seen as spatial representations of a “collective memory”, a compilation of objects and documentation that fulfill a set of criteria affirmed to be historically significant in representing a moment, people and place in time. They construct, along with their institutions and the technologies that disseminate them, the so called histories of a modern nation while documenting a nation’s origins, history and myths.3 The achievement of historical documentation, however, is only grasped through the draining of the “other” in order to amplify the stories of progress. A draining of their cultures, institutions, lands, religions, art and their essence, to ensure their inability to exist in a future through the erasure of their past.4 The colonial act of archival, therefore, deals with both material and psychological erasures of history.5 It deals with both the spatial dissemination of the archive and the ordering of subjectivities of those which are allowed to contribute to said archives.

The contemporary conflict with archival has much to do with questions of what is being archived. Whose voice is being amplified and which narratives are deemed important enough to investigate, excavate and display as preserved artifacts of history? However, the archive is often misunderstood as the object rather than the methodology and bureaucratic criteria that organizes the collection.6 This distinction brings to question not what objects are being collected, but the question of why they are being collected and how they are being used to define a specific narrative of history. This is a spatial question the following research attempts to address, of how the curation and distribution of archival information is also a question of a western-centralization of history. The western criteria of what to archive is a method of affirming the dominance of a colonial narrative that validates an imperial project. This research—as an act of recollection, rather than erasure—attempts to tell a full narrative rather than half of one, which we see in our archives now.

This research brings to question how to effectively counter a framework that is so deeply institutionalized and fabricated by imperial powers that continue to shape space and history. In any sense, the only way to truly decolonize the archival of history is through deconstructing the colonial and racialist foundations that Western and imperial societies are constructed upon. By expanding these modes of spatializing historical and present narratives, we can attempt to expand the narrations of histories and reframe collective memories. This form of research acts to decolonize, reclaiming the narrative through questioning the authenticity of the colonizers’ claims.

COUNTER-ARCHIVING

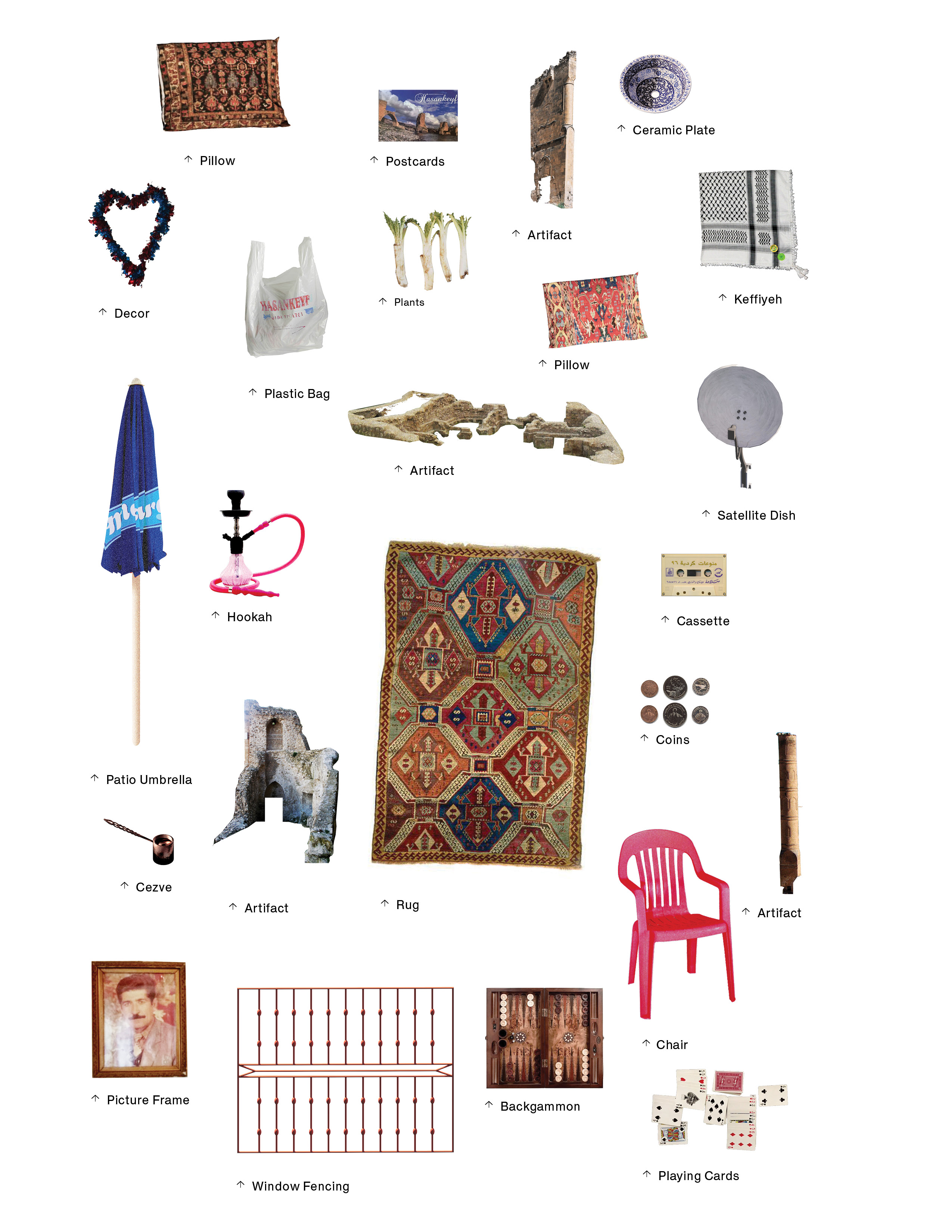

Countering the Turkish Government’s archival of Hasankeyf’s history as one that belongs to Turkey, the first research exploration attempts to collect and document distinctly Kurdish objects, histories, landscapes, and ephemeral practices that were lost to the flooding of Old Hasankeyf. This methodology involves sourcing various imagery, oral accounts, cultural and farming practices to document and reconstruct visual material that memorializes the Kurdish legacy of Hasankeyf in an attempt to counter Turkey’s narrative of a preserved history. This is collected in the form of an archival booklet.

![]()

Figure 2. Archive of cultural items native to Hasankeyf, 2023. Liane Werdina.

COUNTER-DOCUMENTATION

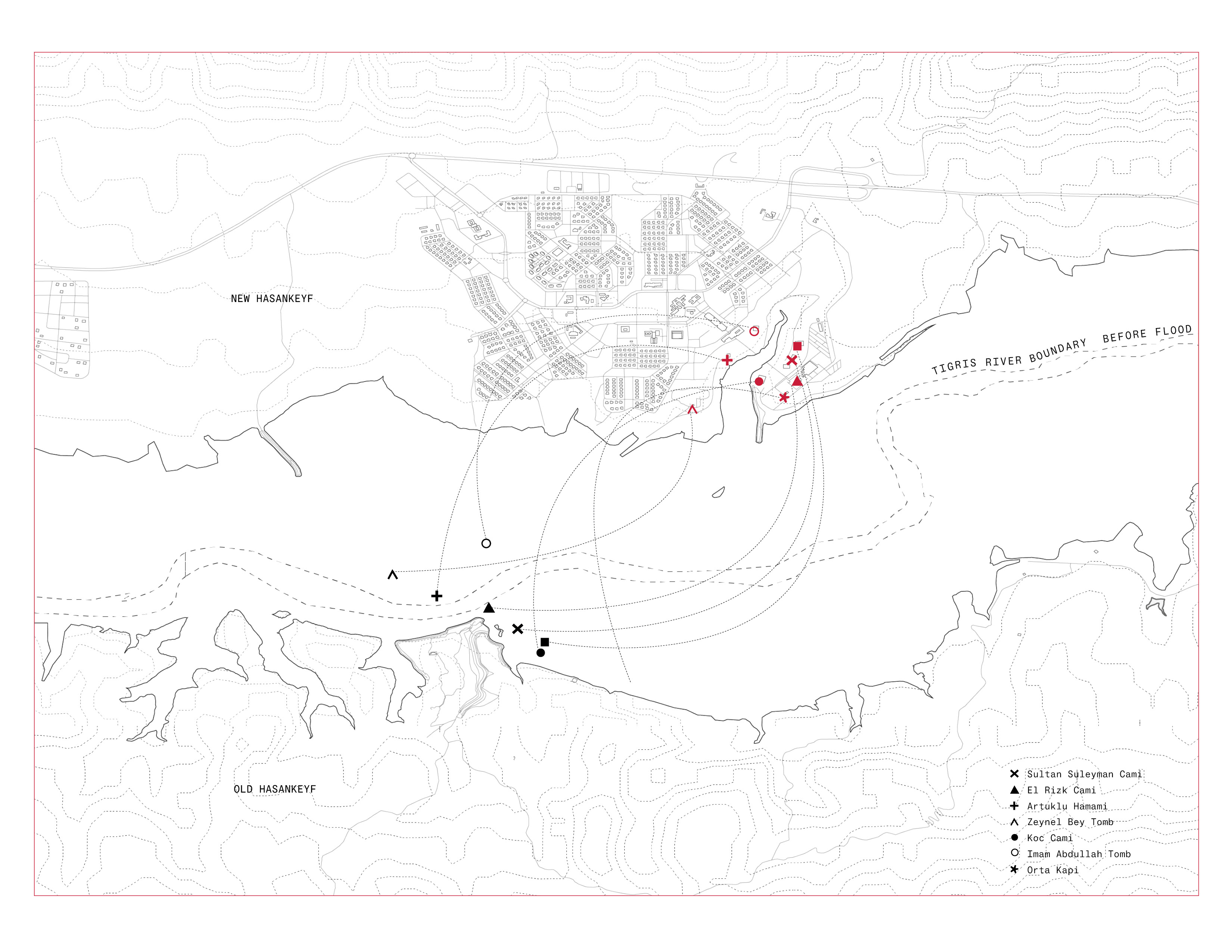

Countering the erasure of Kurdish monuments, language, cities, and names, this methodology subverts the colonial tool of mapping as a method of documentation and legitimization of nationhood. The research explores more fluid methods of mapping, border delineation and documenting what has not been legitimized before.

![]()

Figure 3. Map of the movement of historic monuments and religious infrastructures funded by the Turkish government, prior to the flood of Old Hasankeyf, 2023. Liane Werdina.

Countering the preservation and movement of Kurdish monuments, which were adorned with Turkish flags and symbols of nationhood, moved from their land to Turkish-owned and operated preservation parks. This methodology attempts to counter-map and document the movement and violence of these acts.

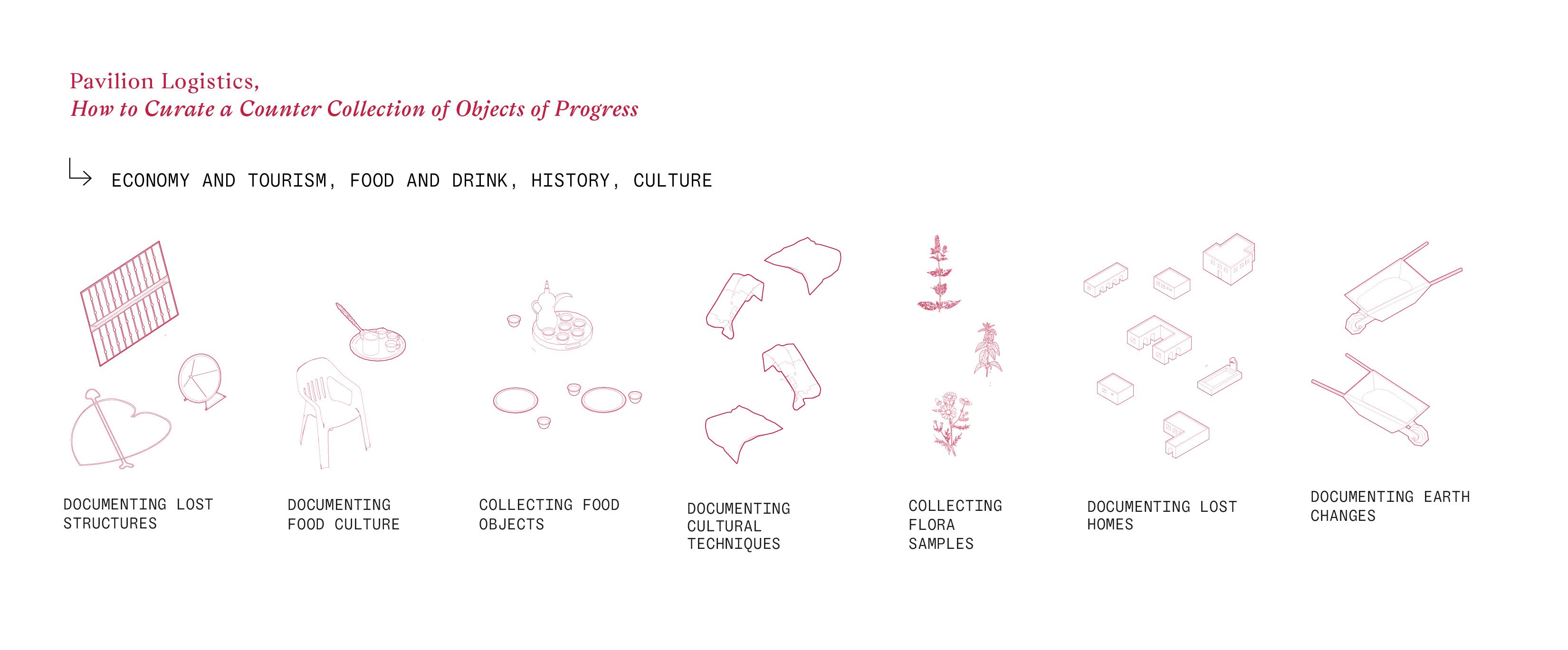

COUNTER-DESIGN

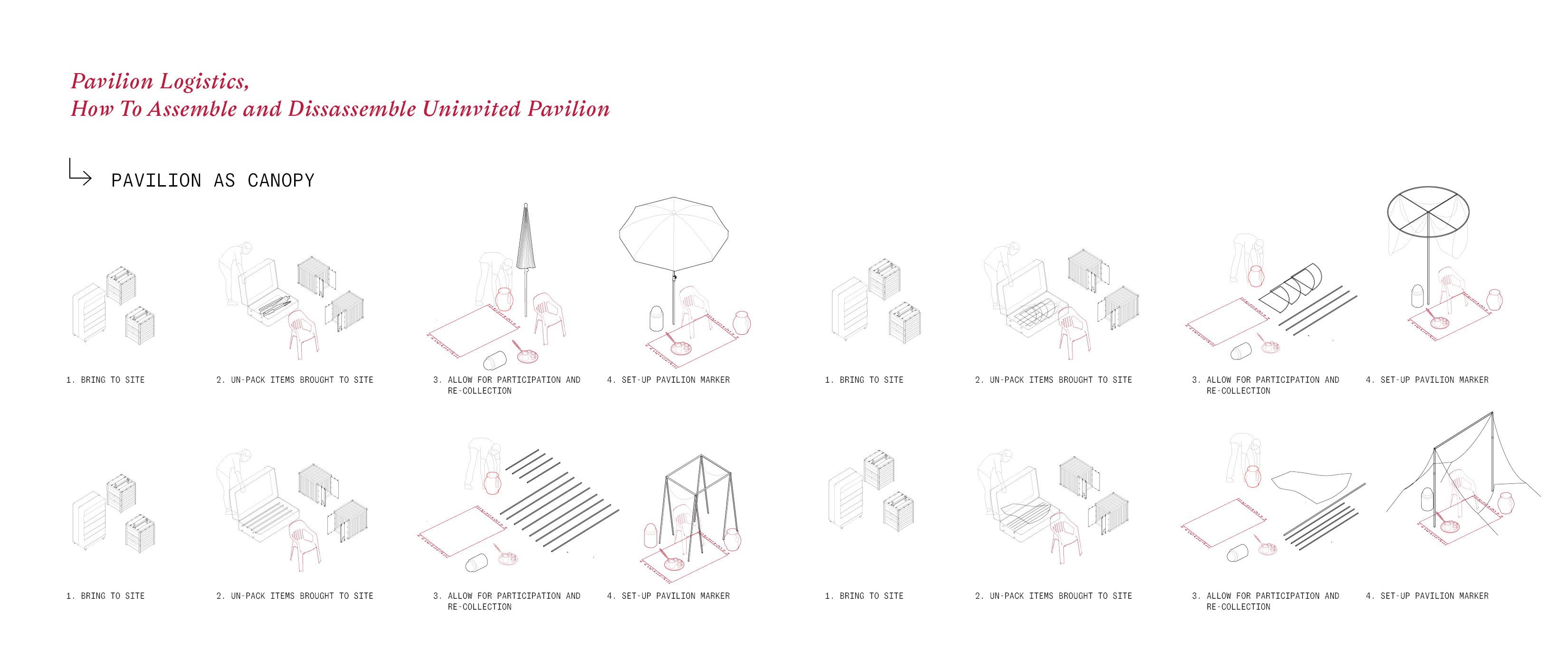

In response to the Turkish government highlighting the Ilisu Dam and other violent infrastructures as objects of technological and ecological progress in World Expos, this methodology explores the subversion of the World Expo for a “landless nation”. The research analyzes how colonial nations use pavilions to mark their identity and explores how this can be subverted as an act of protest through design and physicality.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 4. Pavilion Logistics, 2023. Liane Werdina.

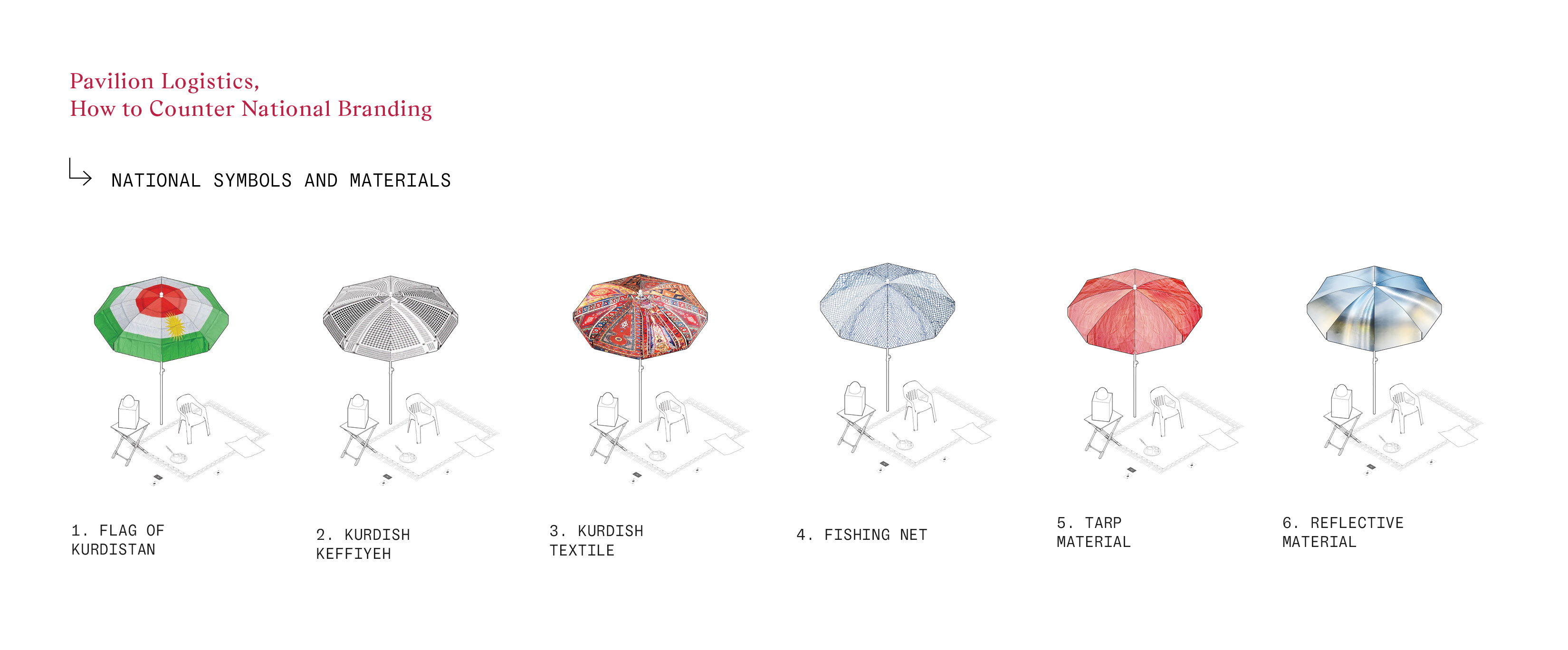

PROTOTYPING

The culmination of the research project involves the exploration of 1:1 scaled mock-ups of the archival objects and pavilions to create scenes of nationhood through the research themes explored.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 5. 1:1 Installation of Kurdish Pavilion structure, 2023. Liane Werdina.

I am interested in design and its socio-political implications, which are closely related to a wider urban setting. My research focuses on how space can be carved to accommodate social and cultural activities as well as how spatial form can contribute to societal frameworks. As a designer, I am interested in how we can use our tools and knowledge of space, design and aesthetics to help dissect and analyze the built environment. I am concerned with the social responsibility of the built environment and how architects and designers contribute to creating meaningful and equitable environments.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Conceptual recreation of Kurdish Pavilion structures, Toronto, 2023. Liane Werdina.

Objects of progress have often buried within them the story of a sacrificed history deemed less valuable. Thus, the act of preservation is a political decision that identifies what history is essential enough to be told - and which can be washed away to make room for progress. This research decodes how the Turkish government’s weaponization of water has been politicized and used to wash away Indigenous Kurdish culture, history, and future existence for Turkish progress. It addresses how the archival and antiquation of select histories is used to ensure an erasure of a Kurdish future. The project uses methods of subverting power projecting curatorial practices, such as world expositions, to protest the Turkish government’s actions and demand autonomy and acknowledgment of Kurdish people and their lost history and future. The research attempts to decenter these notions of progress by counter-archiving what is lost to make room for these objects of progress. Through subversion of hegemonic claims to innocence in the name of progress and environmental development, the aim of the project is to shed a light of truth onto the drowning of Indigenous built history, language, and agriculture as an act of cultural genocide.

CASE STUDY: THE TURKISH ILISU DAM AND DESTRUCTION OF HASANKEYF, KURDISTAN

The culmination of this research analyzes and critiques the Turkish government’s annexation of the Kurdish people of Hasankeyf, through the construction of hydro-infrastructure that in turn is instrumentalized to wash away their land and history. The creation of this infrastructure can be outlined as an act of spatial violence enacted on the Indigenous Kurds of Hasankeyf as a form of cultural genocide. Its ability to displace Indigenous Kurdish communities through the physical washing of archaeological sites, the sinking of monuments, and the loss of livelihoods has consequently been masked in the name of Turkish progress. The organized displacement of these people has been announced as an act of preservation of their history, through the displacement of housing, businesses, monuments and cemeteries.

This research highlights the Turkish government’s violence against the Kurdish people through the creation of this dam and the forced relocation of these people. It addresses this act of displacement as a form of violence rather than preservation, through the removal of locality and history from the land in which it belongs. This then addresses the erasure of physical space, and how it is used as a tool by hegemonic states to disassemble the non-physical histories and memories of the cultures that once inhabited them. The goal of the thesis is to explore methods to counter-colonial narratives of history and find spatial and visual representations of nationhood for those without a state, through the subversion of colonial practices of progress in hopes to disassemble the imperial violences found within them.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY: COUNTERING COLONIAL TECHNIQUES OF PROGRESS

The following research study contributes to the greater discourse on countering colonial methods of documentation in an attempt to subvert narratives of progress and historical preservation that are often at the expense of Indigenous narratives. Colonial and imperial powers have used the occupation of empty land to distort its history in the name of progress. However, objects of progress have often buried within them the story of a sacrificed history deemed less valuable in order to exploit, extract and claim natural resources. Contrary to the imaginary, these lands are not arid, nor are they “undeveloped” and “ancient”. They contain active presents and futures and the act of antiquating them to make room for colonial notions of progress is threatening to their existence. Thus, the act of preservation is a political decision that identifies what history is essential enough to be told—and which can be washed away to make room for progress.

“...objects of progress have often buried within them the story of a sacrificed history deemed less valuable in order to exploit, extract and claim natural resources.”

Nations utilize spatial displays and collections of history such as museums, archives, and world expos as methods of ethnic cleansing hiding behind notions of progress and enlightenment. These formal displays often silence and disclude the voices of the stateless nations that have sacrificed their own history for said progress. Often, in order for stateless nations to achieve or advocate for autonomy and acknowledgment, they must find alternative routes of communication to amplify their voice.

This research explores how to counter this form of history-telling. Through imitation and mimicry of colonial practices of progress such as the archive, the museum and world expositions, nations can begin to construct an anti-colonial resistance method that highlights and exposes the problems with these methods of displaying history—one that is constructed and curated.1

There is a long history of Indigenous or oppressed minority nations utilizing languages of their hegemonic, controlling nations in order to communicate their existence. Within the research project, mimicry is used as an act of anti-colonial resistance to represent and bring voice to the colonized other. It is used to preserve Indigenous identities, whilst discounting the colonial subject’s claims to progress through mockery. The curatorial practice of collection within colonial museum techniques, influenced by anthropological theory, has supported the notion that Indigenous people, artifacts and cultures would be extinct—through death or assimilation —and needed to be documented as a part of a historical past and preserved through objects.2 In an act of protest, and communicating in the formalized colonial languages that oppress them, these communities are able to amplify their voices, announce their presence, and reclaim their narratives that are often stolen within these frameworks.

Archives, museums and expositions have been long seen as spatial representations of a “collective memory”, a compilation of objects and documentation that fulfill a set of criteria affirmed to be historically significant in representing a moment, people and place in time. They construct, along with their institutions and the technologies that disseminate them, the so called histories of a modern nation while documenting a nation’s origins, history and myths.3 The achievement of historical documentation, however, is only grasped through the draining of the “other” in order to amplify the stories of progress. A draining of their cultures, institutions, lands, religions, art and their essence, to ensure their inability to exist in a future through the erasure of their past.4 The colonial act of archival, therefore, deals with both material and psychological erasures of history.5 It deals with both the spatial dissemination of the archive and the ordering of subjectivities of those which are allowed to contribute to said archives.

“This research—as an act of recollection, rather than erasure—attempts to tell a full narrative rather than half of one, which we see in our archives now. ”

The contemporary conflict with archival has much to do with questions of what is being archived. Whose voice is being amplified and which narratives are deemed important enough to investigate, excavate and display as preserved artifacts of history? However, the archive is often misunderstood as the object rather than the methodology and bureaucratic criteria that organizes the collection.6 This distinction brings to question not what objects are being collected, but the question of why they are being collected and how they are being used to define a specific narrative of history. This is a spatial question the following research attempts to address, of how the curation and distribution of archival information is also a question of a western-centralization of history. The western criteria of what to archive is a method of affirming the dominance of a colonial narrative that validates an imperial project. This research—as an act of recollection, rather than erasure—attempts to tell a full narrative rather than half of one, which we see in our archives now.

This research brings to question how to effectively counter a framework that is so deeply institutionalized and fabricated by imperial powers that continue to shape space and history. In any sense, the only way to truly decolonize the archival of history is through deconstructing the colonial and racialist foundations that Western and imperial societies are constructed upon. By expanding these modes of spatializing historical and present narratives, we can attempt to expand the narrations of histories and reframe collective memories. This form of research acts to decolonize, reclaiming the narrative through questioning the authenticity of the colonizers’ claims.

COUNTER-ARCHIVING

Countering the Turkish Government’s archival of Hasankeyf’s history as one that belongs to Turkey, the first research exploration attempts to collect and document distinctly Kurdish objects, histories, landscapes, and ephemeral practices that were lost to the flooding of Old Hasankeyf. This methodology involves sourcing various imagery, oral accounts, cultural and farming practices to document and reconstruct visual material that memorializes the Kurdish legacy of Hasankeyf in an attempt to counter Turkey’s narrative of a preserved history. This is collected in the form of an archival booklet.

Figure 2. Archive of cultural items native to Hasankeyf, 2023. Liane Werdina.

COUNTER-DOCUMENTATION

Countering the erasure of Kurdish monuments, language, cities, and names, this methodology subverts the colonial tool of mapping as a method of documentation and legitimization of nationhood. The research explores more fluid methods of mapping, border delineation and documenting what has not been legitimized before.

Figure 3. Map of the movement of historic monuments and religious infrastructures funded by the Turkish government, prior to the flood of Old Hasankeyf, 2023. Liane Werdina.

Countering the preservation and movement of Kurdish monuments, which were adorned with Turkish flags and symbols of nationhood, moved from their land to Turkish-owned and operated preservation parks. This methodology attempts to counter-map and document the movement and violence of these acts.

COUNTER-DESIGN

In response to the Turkish government highlighting the Ilisu Dam and other violent infrastructures as objects of technological and ecological progress in World Expos, this methodology explores the subversion of the World Expo for a “landless nation”. The research analyzes how colonial nations use pavilions to mark their identity and explores how this can be subverted as an act of protest through design and physicality.

Figure 4. Pavilion Logistics, 2023. Liane Werdina.

PROTOTYPING

The culmination of the research project involves the exploration of 1:1 scaled mock-ups of the archival objects and pavilions to create scenes of nationhood through the research themes explored.

Figure 5. 1:1 Installation of Kurdish Pavilion structure, 2023. Liane Werdina.

- J. J. Ghaddar and Michelle Caswell, “‘To Go beyond’: Towards a Decolonial Archival Praxis,” Archival Science 19, no. 2 (May 28, 2019): 71–85.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Moa Carlsson and Samia Henni, Thinking Through and Against the Archive: Interview with Samia Henni (2021).

- Ghaddar and Caswell, “To Go Beyond,” 71–85.