In Conversation with Miles Gertler

BIOGRAPHY

Miles Gertler is an artist and co-director of Common Accounts, an office for architectural inquiry that currently operates between Toronto and Madrid. His work in architecture, academia, and visual art examines self-design in virtual and material realms, and documents design intelligence that often passes under the radar of the discipline in areas like fitness, death, military logistics, and ritual. Gertler’s work and writing has been featured in Perspecta, e-flux, 032c, PIN-UP, Arquitectura Viva, Canadian Architect, Frame, Neo2, El Pais, The Cornell Journal of Architecture, The Globe and Mail, The Architectural Review, and the Avery Review.

He has exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale, the MMCA Seoul, the Seoul Museum of Art, Matadero Madrid, Art Jameel, Azkuna Zentroa, the Cube Design Museum, the Bienal de Arquitectura Española, the Istanbul Design Biennial, the Seoul Biennial of Architecture and Urbanism, the Canadian Centre for Architecture, MOCA (Toronto), a83 gallery, and Corkin Gallery. Gertler was a 2023 resident at Palazzo Monti in Brescia, Italy, and has served on the Board of Directors at Mercer Union, A Centre for Contemporary Art, since 2019. He is Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream at the University of Toronto’s Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design, and studied architecture at Princeton and the University of Waterloo. Gertler was a recipient of the 2023 Architectural League Prize for Young Architects + Designers from the Architectural League of New York.

Miles Gertler is an artist and co-director of Common Accounts, an office for architectural inquiry that currently operates between Toronto and Madrid. His work in architecture, academia, and visual art examines self-design in virtual and material realms, and documents design intelligence that often passes under the radar of the discipline in areas like fitness, death, military logistics, and ritual. Gertler’s work and writing has been featured in Perspecta, e-flux, 032c, PIN-UP, Arquitectura Viva, Canadian Architect, Frame, Neo2, El Pais, The Cornell Journal of Architecture, The Globe and Mail, The Architectural Review, and the Avery Review.

He has exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale, the MMCA Seoul, the Seoul Museum of Art, Matadero Madrid, Art Jameel, Azkuna Zentroa, the Cube Design Museum, the Bienal de Arquitectura Española, the Istanbul Design Biennial, the Seoul Biennial of Architecture and Urbanism, the Canadian Centre for Architecture, MOCA (Toronto), a83 gallery, and Corkin Gallery. Gertler was a 2023 resident at Palazzo Monti in Brescia, Italy, and has served on the Board of Directors at Mercer Union, A Centre for Contemporary Art, since 2019. He is Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream at the University of Toronto’s Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design, and studied architecture at Princeton and the University of Waterloo. Gertler was a recipient of the 2023 Architectural League Prize for Young Architects + Designers from the Architectural League of New York.

Facilitated by the Scaffold* Editorial Team in February 2024.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

Figure 1. Clima Fitness, Madrid, 2023. Photo by Geray Mena.

Q: Could you briefly explain the breadth of your work as it spans both architecture and visual arts?

My work operates between two channels. One is my collaborative design practice with Igor Bragado—we have a studio called Common Accounts, which we founded upon finishing graduate school. Most of our work there has an interest in self-design, the body, ritual and procession, and the materializations and logistics of ceremony. A lot of our work looks at subject matter like death, plastic surgery, cosmetics, and fitness. Historically, we see these as the sites where our interests have been mobilized as pragmatic tools for city building. We work between Toronto and Madrid—so our work covers a wide expanse.

Secondly, I also have a solo visual arts practice in which I produce work in installation, image, and sculpture. I’ve shown mostly with Corkin Gallery here in Toronto, but I’ve exhibited internationally. My work is interested in alternative aesthetic histories of technology. Both my solo project and my work with Common Accounts develop from an interest in under-the-radar subject matter. In both cases, we’re deeply informed by history and visual analysis of historical images and archive materials.

Q: Could you tell us more about the emergence of your work as it relates to the human body and death? How did you become interested in these themes?

Death was the subject of the thesis project that Igor and I jointly authored at Princeton, where we completed grad school. We were interested in the ways that architecture could improve daily life—and with death, everyone’s a client. Death is one of these areas where architecture has largely surrendered its interest in the last fifty or sixty years, but there’s a really rich history there. There’s amazing work from the 1920s through the 1960s and 70s—from both modernists and postmodernists. At the same time architects were interested in the poetry of the cemetery, or of funeral regulation, administrative forces were starting to structure how death was managed and how it would operate as an economy rather than as a social practice. So we became interested in reversing the evident distance between death and daily life that we were seeing, in order to produce new forms of value from a proximity to death. We felt that by bringing death back into daily life, that there would be social, environmental, and material value to be gained.

We also noticed that in many cities, death-related issues in urban design were reaching new extremes. For instance, many cities are running out of space for burial. This is changing our attitudes toward perpetuity—how long does someone remain in a cemetery or in a grave before we feel comfortable exhuming them to make room for new, more recently deceased urban citizens? These are real issues that urban planners and city officials are dealing with, in all sorts of places around the world, that we can’t continue to ignore. It’s something that we thought architecture would do well to consider.

In our work on death, it didn’t take long before we encountered considerations of healing, maintenance and fitness, and also general self-fashioning of the body. We realize that death inherently involves acts of self-design—how we imagine ourselves to be or how we instruct our loved ones to kind of take care of us after we die. When death is seen as one of many sites of self design that are encountered in daily life, you can start to place all of these actions in which self-design is enacted on a spectrum: between death and the deconstruction of the body, and health, maintenance, and the construction of the body. If you think about those things as being on the same axis, any act of physical upkeep can be understood as having some relationship to death.

Considering this, we started to look into architectural history and theory, particularly investigating the way in which death acts as a protagonist in the work of figures like Sigfried Giedion—particularly in his chapter on Meat in “Mechanization Takes Command”.[1] Other writers, like Beatriz Colomina, observed death and spin-off technologies emerging from violent origins and the way in which those start to infiltrate daily life.[2] We became really interested in a world where death was all around us, in our built and lived environment, and yet increasingly invisible. We found that to be a really interesting paradox in which to work.

![]()

Figure 2. You Are Well Liked in Your Community, Toronto, 2023. Photo by Jackson Klie.

Q: We’re particularly interested in architecture’s role in memorialization, monument-making, and collective ritual. Have you noticed that this has changed significantly in the digital era? What does this shift towards the Internet and online footprints in afterlives mean for the discipline? What does it mean for death?

A lot has changed in this space since we started working eight years ago. A lot of our early work was interested in memorializing all different forms of remains. We were interested in not only building new funeral traditions around the material body and remains disposition—which is how we say disposal in the death care industry—but also in the virtual afterlife, and what you do with the digital remains of a life lived online. We thought, at first kind of naively, that it would be interesting to capture and upload all of the ephemera, photos, comments, social media activity to an online server, so that a funeral ceremony would occur in the material and digital realms. And in some ways, that actually just modeled what we were already observing—that social media sites like Facebook and YouTube had unwittingly become sites for memorial, commiseration, and mourning. So in our mind, this was already happening, and the funeral industry had failed to recognize it.

Nonetheless, since we began that work, all sorts of things have happened—significant data breaches, Cambridge Analytica, the prospect of widespread manipulation through social media, have completely transformed attitudes around data access. In our own work on the digital afterlife and digital remains, we decided to create a black box server in which you could upload and crowdsource all of the digital remains particular to one person. All of those materials would be collected and sealed off for posterity, so you knew they were preserved in some way, but inaccessibly. We thought this modeled existing historical conceptions of the afterlife—this belief that something continues to persist, but it’s hidden from us. But this all speaks to larger interests that people have in how to create meaningful funeral rituals in contemporary daily life. We’ve met with funeral service providers and large cemetery owners, and they’re really interested in how to make, for example, mausolea that might incorporate visual and digital media.

Contemporary requests for multimedial mausolea may excite funeral companies, but also pose a concern for the perpetual management and preservation of technologies involved. This is similar to the line of thinking that museums and collecting institutions are subject to: MoMA has to consider how to ensure that video art pieces collected in the 1980s are still operable through physical hardware that may be rendered obsolete by advancing technology. These are the kinds of concerns that archives and collections staff have to deal with—and so there is the prospect that cemeteries might incorporate more of that in the near future as well.

Q: Much of your work relates to the physical elements of death. A mausoleum, for instance, is very physical. But then you also address digital phenomena such as servers or the cloud. How much of your work exists only in the digital space and how much of it would you say is primarily physical? How would you say the difference in its spatial existence fundamentally alters the nature of the work itself and the process of creating it?

A lot of our work is exclusively digital. We’re a remote office, so we work on many of the same projects at the same time in the same files. Most of that design labor and research is in our Dropbox server online, so we can both simultaneously access it. This workflow has definitely reduced the material output of our office. For instance, we don’t produce many physical models because their utility is limited by the fact that only one of us can have a close encounter with it. When we do make models or physical artifacts, they’re often more for exhibition or the presentation or communication of ideas to an audience beyond our office. Because of the digital context of our work, a lot of the projects that we’re engaged in seek to bridge the IRL with the online.

“The outlet of making something with your own hands becomes extra valuable in the context of our work.”

These connections have attracted the increasing interest of architects everywhere—we’re seeing the increasing spatialization of digital media, where it has started to intervene in daily life more and more. I think the field is conscious of this and always has been. The work in my visual arts practice is abundantly material. Typical Oasis, a recent show that I did at Corkin Gallery, was centered around these cardboard facsimiles of familiar objects. I found cardboard to be generally resistant to process labor in digital space, because in the work I was doing, the range of what cardboard could do—limited by its laminations and pulp—needed to be tested with a blade, by hand. This project developed from a month-long residency that I did in Italy last summer, which was an offline period for me. I was working in the studio with a knife, a cutting board, and a lot of super glue, and experimenting with the mechanics and material qualities of cardboard. I think that there’s probably a little bit of digital fatigue that sets in from running an overwhelmingly online practice. The outlet of making something with your own hands becomes extra valuable in the context of our work.

![]()

Figure 3. Typical Oasis, Toronto, 2023. Miles Gertler.

Q: Your formal background is in architecture—in the design of buildings and space. How has this training influenced your artistic process? Where does one discipline end and the other begin, or do both converge in the majority of your work?

I’m definitely a product of my training. For a long time, I shied away from identifying as a visual artist. But I think it’s simply descriptive of the reality of that channel of my work. The first images that I made that were exhibited in a gallery were simply architecture to me. They were images of buildings in landscape photo collages that I produced as a risograph zine. Eventually, this work fell into the hands of my now-gallerist Jane Corkin. A year later, I developed a process to translate those images to larger, editioned prints, and we did our first show together.

Coincidentally, I work with a gallery that is interested in architectural subject matter. Jane is someone who has always cultivated an interest in architecture—her current gallery was designed by Bridget Shim and Howard Sutcliffe, and her prior gallery was designed by Barton Meyers. Of course, visual art and architecture are different communities and they have different languages, so there’s some code switching that you have to engage in when you’re moving between those two spaces.

For the last five years, I’ve been on the board of directors at Mercer Union, which is an artist-run center in Toronto that exhibits and commissions work from fantastic artists, often at pivotal moments in their careers. My proximity to this work has helped improve my own fluency in reading and discussing visual art. It’s also helped that Common Accounts regularly exhibits in museum or gallery contexts. Architects tend to over-explain and over-determine every decision—whereas in visual art, presentation and communication of decision-making tends to be subtle. Through Common Accounts’s exhibitions and our proximity to visual art, we’ve learned how to make work that can be impactful without being didactic.

Q: Can you describe some of the key tools that you work with in your practice? Are there any media that might be considered unconventional in the realms of visual art? In architecture?

We are largely image makers. Drawing, visualization, and increasingly work in video and the moving image are a core part of what we do—it’s part of our larger effort in narrative construction. Following this logic, the tools that we use are really whichever tools serve that purpose. We work with a lot of different techniques and methods to advance our research and creative output. One has to closely read texts, examine artifacts, and conduct visual analysis. These practices extend to contemporary and popular culture—we absorb it. We are big consumers of culture in its many forms, in exhibitions, plays, films, reality TV. I think that we are interested in being an architecture office that communicates principally with a wide public—so all of these mediums are on the table for us and really quite compelling.

To that end, I think some of the formats that we like to work in are through writing and interviews. Often, we’re in conversation with people or media that don’t necessarily belong in architectural practice, or fly under the radar. We’ve written reviews of the set design of plays and we’ve interviewed artists whose work we’re fascinated by. A lot of this inquiry aims to bring to light topics that could be of interest to the discipline at large.

![]()

Figure 4. Superlith & Seven, 2017. Miles Gertler.

Q: Your office is occasionally described as an experimental design practice. What has been the role of experimentation in your practice? What does this look like?

On the one hand, the “experimental” piece simply acknowledges the many different formats we work in. We build environments and we produce physical spaces, but we also produce ideas and discourse in visual arts, artifacts, and media. We also lecture and speak publicly in discussion with other actors in architecture and its allied fields. So really, I think the experimentation describes the breadth of output.

I think we’re also trying to imagine what it is to move through the world with an architectural perspective and skill set, and what utility that might have beyond simply making buildings. In one regard, it’s about the formats that we work in, and in the other, it’s about which communities you’re a part of, what relationships you foster with which creative actors and with which kinds of protagonists. There have been many forms of radical architectural practice—even just in the last century—which is to say that we’re not exceptional in that sense. There are many who have modeled the kind of practice we want to be. We see ways in which architects in the past have operated, in modalities that are really exciting and interesting to us. If anything, we’re simply trying to understand how they worked and rehearse the aspects of their practice that strike us as fascinating, and try to reclaim some of that for architectural practice today.

Q: How would you define design research as it relates to your practice?

The field seems somewhat split even on the use of the word research in the context of design. Some prefer the word “inquiry” because of research’s associations with scientific procedure and academic protocol. I’m sort of ambivalent. The way I see it, design research is the production of knowledge and the process of discovery that produces innovation in design. I think that innovation for us is simply pushing the needle slightly—we’re fine with microscopic, incremental advancement in our space.

“My encouragement to young designers wishing to embark on their own research practice is simply to apply your architectural lens and knowledge to material that hasn’t been considered by the discipline before.”

Design research can be whatever you argue constitutes design. Much of the time, we’re surrounded by so much media and material—and much of it is designed, although we don’t typically acknowledge it as such. One thing that we’ve always believed at Common Accounts is that most of the design intelligence in the world operates beyond the scope of architecture and the design disciplines. My encouragement to young designers wishing to embark on their own research practice is simply to apply your architectural lens and knowledge to material that hasn’t been considered by the discipline before. Through rigorous analysis and engagement, bring this to the discipline’s attention—we can all learn a lot from these other intelligences.

![]()

Figure 5. Scaffold for Eternal Smiles, Toronto, 2021. Common Accounts.

Q: Last but not least, we couldn’t help but notice that Common Accounts has an installation titled Scaffolds, which claims to “materialize architectural MP4 memes.” Could you tell us more about this work and what inspired it?

Scaffolds were two mixed digital media artworks that we exhibited at an art fair with Corkin Gallery in 2021. We’d been interested in creating visual art artifacts for some time. We’d also noticed in our own practice that form-making often becomes an apparatus. In one of our pavilions, you’ll be able to identify the discrete elements that assemble to create a spatial installation. The technique of scaffolding is something that exists in these artworks, but also in our practice more broadly as a response to form-making and to bringing together various legible, constituent parts—of its method as well as form.

In these pieces, we used miniature video screens—on one, we had looping animations of hands in various gestures changing their expressions. And on the other, the Scaffold for Eternal Smiles included a looping 360° view of this parade car that we had imagined as part of our series FOMO-Stock, which was commissioned for Perspecta.

So on the one hand, these are moving image works. Whether it’s a drawing or a video work on the wall, we’re interested in developing object quality around otherwise 2D artifacts. The scaffolds in these works become the technique that we use not only to attach and exhibit the video works, but also to render them as part of an environment.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Clima Fitness, Madrid, 2023. Photo by Geray Mena.

Q: Could you briefly explain the breadth of your work as it spans both architecture and visual arts?

My work operates between two channels. One is my collaborative design practice with Igor Bragado—we have a studio called Common Accounts, which we founded upon finishing graduate school. Most of our work there has an interest in self-design, the body, ritual and procession, and the materializations and logistics of ceremony. A lot of our work looks at subject matter like death, plastic surgery, cosmetics, and fitness. Historically, we see these as the sites where our interests have been mobilized as pragmatic tools for city building. We work between Toronto and Madrid—so our work covers a wide expanse.

Secondly, I also have a solo visual arts practice in which I produce work in installation, image, and sculpture. I’ve shown mostly with Corkin Gallery here in Toronto, but I’ve exhibited internationally. My work is interested in alternative aesthetic histories of technology. Both my solo project and my work with Common Accounts develop from an interest in under-the-radar subject matter. In both cases, we’re deeply informed by history and visual analysis of historical images and archive materials.

Q: Could you tell us more about the emergence of your work as it relates to the human body and death? How did you become interested in these themes?

Death was the subject of the thesis project that Igor and I jointly authored at Princeton, where we completed grad school. We were interested in the ways that architecture could improve daily life—and with death, everyone’s a client. Death is one of these areas where architecture has largely surrendered its interest in the last fifty or sixty years, but there’s a really rich history there. There’s amazing work from the 1920s through the 1960s and 70s—from both modernists and postmodernists. At the same time architects were interested in the poetry of the cemetery, or of funeral regulation, administrative forces were starting to structure how death was managed and how it would operate as an economy rather than as a social practice. So we became interested in reversing the evident distance between death and daily life that we were seeing, in order to produce new forms of value from a proximity to death. We felt that by bringing death back into daily life, that there would be social, environmental, and material value to be gained.

“Death is one of these areas where architecture has largely surrendered its interest in the last fifty or sixty years, but there’s a really rich history there.”

We also noticed that in many cities, death-related issues in urban design were reaching new extremes. For instance, many cities are running out of space for burial. This is changing our attitudes toward perpetuity—how long does someone remain in a cemetery or in a grave before we feel comfortable exhuming them to make room for new, more recently deceased urban citizens? These are real issues that urban planners and city officials are dealing with, in all sorts of places around the world, that we can’t continue to ignore. It’s something that we thought architecture would do well to consider.

In our work on death, it didn’t take long before we encountered considerations of healing, maintenance and fitness, and also general self-fashioning of the body. We realize that death inherently involves acts of self-design—how we imagine ourselves to be or how we instruct our loved ones to kind of take care of us after we die. When death is seen as one of many sites of self design that are encountered in daily life, you can start to place all of these actions in which self-design is enacted on a spectrum: between death and the deconstruction of the body, and health, maintenance, and the construction of the body. If you think about those things as being on the same axis, any act of physical upkeep can be understood as having some relationship to death.

Considering this, we started to look into architectural history and theory, particularly investigating the way in which death acts as a protagonist in the work of figures like Sigfried Giedion—particularly in his chapter on Meat in “Mechanization Takes Command”.[1] Other writers, like Beatriz Colomina, observed death and spin-off technologies emerging from violent origins and the way in which those start to infiltrate daily life.[2] We became really interested in a world where death was all around us, in our built and lived environment, and yet increasingly invisible. We found that to be a really interesting paradox in which to work.

Figure 2. You Are Well Liked in Your Community, Toronto, 2023. Photo by Jackson Klie.

Q: We’re particularly interested in architecture’s role in memorialization, monument-making, and collective ritual. Have you noticed that this has changed significantly in the digital era? What does this shift towards the Internet and online footprints in afterlives mean for the discipline? What does it mean for death?

A lot has changed in this space since we started working eight years ago. A lot of our early work was interested in memorializing all different forms of remains. We were interested in not only building new funeral traditions around the material body and remains disposition—which is how we say disposal in the death care industry—but also in the virtual afterlife, and what you do with the digital remains of a life lived online. We thought, at first kind of naively, that it would be interesting to capture and upload all of the ephemera, photos, comments, social media activity to an online server, so that a funeral ceremony would occur in the material and digital realms. And in some ways, that actually just modeled what we were already observing—that social media sites like Facebook and YouTube had unwittingly become sites for memorial, commiseration, and mourning. So in our mind, this was already happening, and the funeral industry had failed to recognize it.

Nonetheless, since we began that work, all sorts of things have happened—significant data breaches, Cambridge Analytica, the prospect of widespread manipulation through social media, have completely transformed attitudes around data access. In our own work on the digital afterlife and digital remains, we decided to create a black box server in which you could upload and crowdsource all of the digital remains particular to one person. All of those materials would be collected and sealed off for posterity, so you knew they were preserved in some way, but inaccessibly. We thought this modeled existing historical conceptions of the afterlife—this belief that something continues to persist, but it’s hidden from us. But this all speaks to larger interests that people have in how to create meaningful funeral rituals in contemporary daily life. We’ve met with funeral service providers and large cemetery owners, and they’re really interested in how to make, for example, mausolea that might incorporate visual and digital media.

Contemporary requests for multimedial mausolea may excite funeral companies, but also pose a concern for the perpetual management and preservation of technologies involved. This is similar to the line of thinking that museums and collecting institutions are subject to: MoMA has to consider how to ensure that video art pieces collected in the 1980s are still operable through physical hardware that may be rendered obsolete by advancing technology. These are the kinds of concerns that archives and collections staff have to deal with—and so there is the prospect that cemeteries might incorporate more of that in the near future as well.

Q: Much of your work relates to the physical elements of death. A mausoleum, for instance, is very physical. But then you also address digital phenomena such as servers or the cloud. How much of your work exists only in the digital space and how much of it would you say is primarily physical? How would you say the difference in its spatial existence fundamentally alters the nature of the work itself and the process of creating it?

A lot of our work is exclusively digital. We’re a remote office, so we work on many of the same projects at the same time in the same files. Most of that design labor and research is in our Dropbox server online, so we can both simultaneously access it. This workflow has definitely reduced the material output of our office. For instance, we don’t produce many physical models because their utility is limited by the fact that only one of us can have a close encounter with it. When we do make models or physical artifacts, they’re often more for exhibition or the presentation or communication of ideas to an audience beyond our office. Because of the digital context of our work, a lot of the projects that we’re engaged in seek to bridge the IRL with the online.

“The outlet of making something with your own hands becomes extra valuable in the context of our work.”

These connections have attracted the increasing interest of architects everywhere—we’re seeing the increasing spatialization of digital media, where it has started to intervene in daily life more and more. I think the field is conscious of this and always has been. The work in my visual arts practice is abundantly material. Typical Oasis, a recent show that I did at Corkin Gallery, was centered around these cardboard facsimiles of familiar objects. I found cardboard to be generally resistant to process labor in digital space, because in the work I was doing, the range of what cardboard could do—limited by its laminations and pulp—needed to be tested with a blade, by hand. This project developed from a month-long residency that I did in Italy last summer, which was an offline period for me. I was working in the studio with a knife, a cutting board, and a lot of super glue, and experimenting with the mechanics and material qualities of cardboard. I think that there’s probably a little bit of digital fatigue that sets in from running an overwhelmingly online practice. The outlet of making something with your own hands becomes extra valuable in the context of our work.

Figure 3. Typical Oasis, Toronto, 2023. Miles Gertler.

Q: Your formal background is in architecture—in the design of buildings and space. How has this training influenced your artistic process? Where does one discipline end and the other begin, or do both converge in the majority of your work?

I’m definitely a product of my training. For a long time, I shied away from identifying as a visual artist. But I think it’s simply descriptive of the reality of that channel of my work. The first images that I made that were exhibited in a gallery were simply architecture to me. They were images of buildings in landscape photo collages that I produced as a risograph zine. Eventually, this work fell into the hands of my now-gallerist Jane Corkin. A year later, I developed a process to translate those images to larger, editioned prints, and we did our first show together.

Coincidentally, I work with a gallery that is interested in architectural subject matter. Jane is someone who has always cultivated an interest in architecture—her current gallery was designed by Bridget Shim and Howard Sutcliffe, and her prior gallery was designed by Barton Meyers. Of course, visual art and architecture are different communities and they have different languages, so there’s some code switching that you have to engage in when you’re moving between those two spaces.

“Of course, visual art and architecture are different communities and they have different languages, so there’s some code switching that you have to engage in when you’re moving between those two spaces.”

For the last five years, I’ve been on the board of directors at Mercer Union, which is an artist-run center in Toronto that exhibits and commissions work from fantastic artists, often at pivotal moments in their careers. My proximity to this work has helped improve my own fluency in reading and discussing visual art. It’s also helped that Common Accounts regularly exhibits in museum or gallery contexts. Architects tend to over-explain and over-determine every decision—whereas in visual art, presentation and communication of decision-making tends to be subtle. Through Common Accounts’s exhibitions and our proximity to visual art, we’ve learned how to make work that can be impactful without being didactic.

Q: Can you describe some of the key tools that you work with in your practice? Are there any media that might be considered unconventional in the realms of visual art? In architecture?

We are largely image makers. Drawing, visualization, and increasingly work in video and the moving image are a core part of what we do—it’s part of our larger effort in narrative construction. Following this logic, the tools that we use are really whichever tools serve that purpose. We work with a lot of different techniques and methods to advance our research and creative output. One has to closely read texts, examine artifacts, and conduct visual analysis. These practices extend to contemporary and popular culture—we absorb it. We are big consumers of culture in its many forms, in exhibitions, plays, films, reality TV. I think that we are interested in being an architecture office that communicates principally with a wide public—so all of these mediums are on the table for us and really quite compelling.

To that end, I think some of the formats that we like to work in are through writing and interviews. Often, we’re in conversation with people or media that don’t necessarily belong in architectural practice, or fly under the radar. We’ve written reviews of the set design of plays and we’ve interviewed artists whose work we’re fascinated by. A lot of this inquiry aims to bring to light topics that could be of interest to the discipline at large.

Figure 4. Superlith & Seven, 2017. Miles Gertler.

Q: Your office is occasionally described as an experimental design practice. What has been the role of experimentation in your practice? What does this look like?

On the one hand, the “experimental” piece simply acknowledges the many different formats we work in. We build environments and we produce physical spaces, but we also produce ideas and discourse in visual arts, artifacts, and media. We also lecture and speak publicly in discussion with other actors in architecture and its allied fields. So really, I think the experimentation describes the breadth of output.

I think we’re also trying to imagine what it is to move through the world with an architectural perspective and skill set, and what utility that might have beyond simply making buildings. In one regard, it’s about the formats that we work in, and in the other, it’s about which communities you’re a part of, what relationships you foster with which creative actors and with which kinds of protagonists. There have been many forms of radical architectural practice—even just in the last century—which is to say that we’re not exceptional in that sense. There are many who have modeled the kind of practice we want to be. We see ways in which architects in the past have operated, in modalities that are really exciting and interesting to us. If anything, we’re simply trying to understand how they worked and rehearse the aspects of their practice that strike us as fascinating, and try to reclaim some of that for architectural practice today.

Q: How would you define design research as it relates to your practice?

The field seems somewhat split even on the use of the word research in the context of design. Some prefer the word “inquiry” because of research’s associations with scientific procedure and academic protocol. I’m sort of ambivalent. The way I see it, design research is the production of knowledge and the process of discovery that produces innovation in design. I think that innovation for us is simply pushing the needle slightly—we’re fine with microscopic, incremental advancement in our space.

“My encouragement to young designers wishing to embark on their own research practice is simply to apply your architectural lens and knowledge to material that hasn’t been considered by the discipline before.”

Design research can be whatever you argue constitutes design. Much of the time, we’re surrounded by so much media and material—and much of it is designed, although we don’t typically acknowledge it as such. One thing that we’ve always believed at Common Accounts is that most of the design intelligence in the world operates beyond the scope of architecture and the design disciplines. My encouragement to young designers wishing to embark on their own research practice is simply to apply your architectural lens and knowledge to material that hasn’t been considered by the discipline before. Through rigorous analysis and engagement, bring this to the discipline’s attention—we can all learn a lot from these other intelligences.

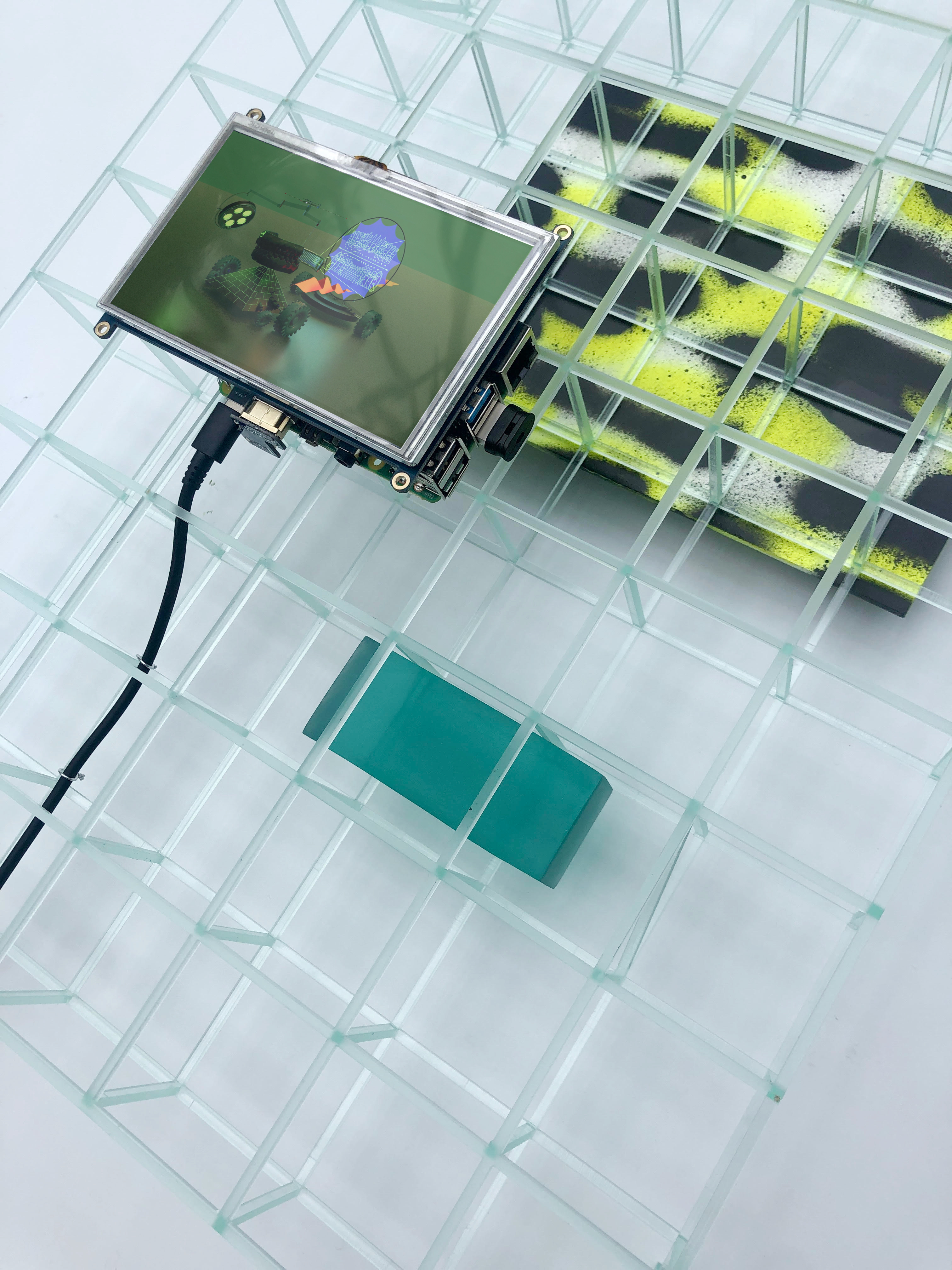

Figure 5. Scaffold for Eternal Smiles, Toronto, 2021. Common Accounts.

Q: Last but not least, we couldn’t help but notice that Common Accounts has an installation titled Scaffolds, which claims to “materialize architectural MP4 memes.” Could you tell us more about this work and what inspired it?

Scaffolds were two mixed digital media artworks that we exhibited at an art fair with Corkin Gallery in 2021. We’d been interested in creating visual art artifacts for some time. We’d also noticed in our own practice that form-making often becomes an apparatus. In one of our pavilions, you’ll be able to identify the discrete elements that assemble to create a spatial installation. The technique of scaffolding is something that exists in these artworks, but also in our practice more broadly as a response to form-making and to bringing together various legible, constituent parts—of its method as well as form.

In these pieces, we used miniature video screens—on one, we had looping animations of hands in various gestures changing their expressions. And on the other, the Scaffold for Eternal Smiles included a looping 360° view of this parade car that we had imagined as part of our series FOMO-Stock, which was commissioned for Perspecta.

So on the one hand, these are moving image works. Whether it’s a drawing or a video work on the wall, we’re interested in developing object quality around otherwise 2D artifacts. The scaffolds in these works become the technique that we use not only to attach and exhibit the video works, but also to render them as part of an environment.