Piecing a Mosaic: Designing for a Multicultural City Through Community-Oriented Inquiry

MUSKAN GOEL

I am currently in the final year of the Master of Architecture program at University of Toronto. I hold a Bachelor of Architectural Studies from McEwen School of Architecture, Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario. Originally, I grew up in Mumbai, India where most of my family still resides. After moving to Canada to pursue architectural education I have also explored my interests in traveling various countries, many of them in Europe and Scandinavian regions. I enjoy various forms of public projects, interactions and social conversations around design and our built environment. I am registered as a student associate with the Ontario Association of Architects and members with Toronto Society of Architects as well as Society of South Asian Architects in Canada.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

![]()

![]()

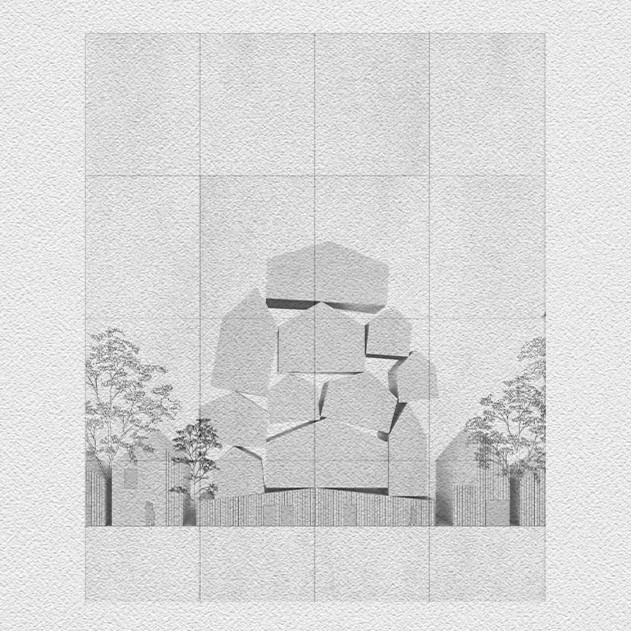

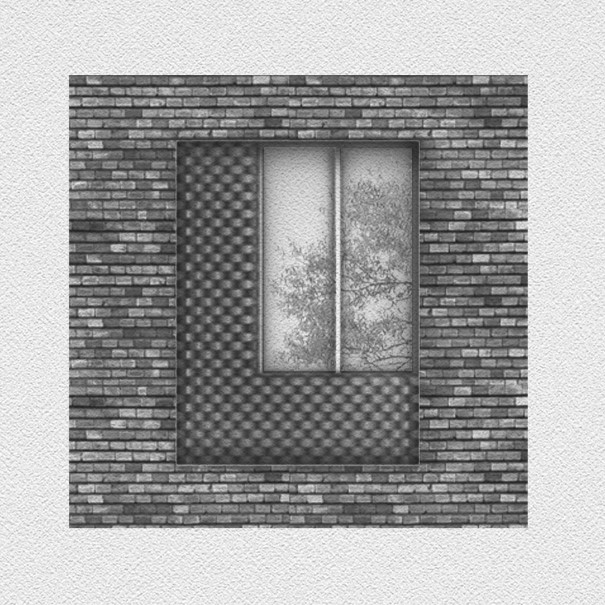

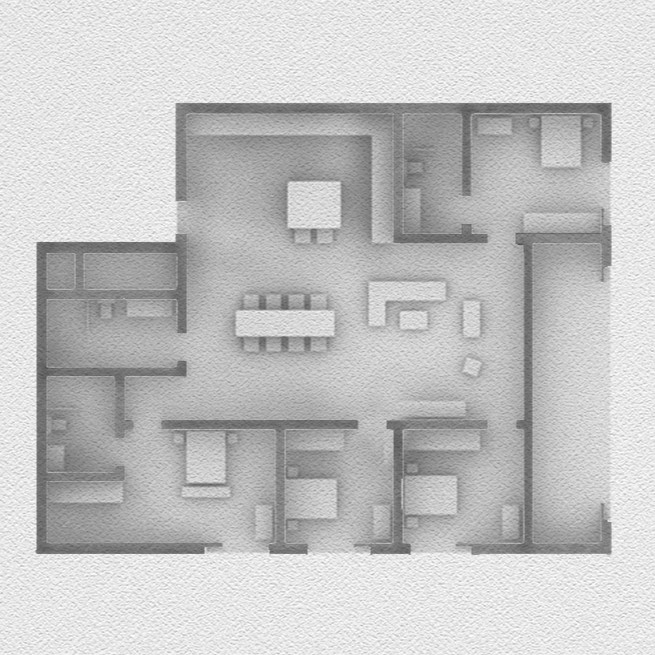

Figure 1. Conceptual Diagram, Material Exploration, & Spatial Organization, 2023-2024. Muskan Goel.

Multi-generational living is a traditional model where large households dwell under one roof and share knowledge and activities, such as cooking and dining. There are multiple reasons why this model of living might transpose itself into the existing Western home that characterizes our suburban landscape. Cultural practices, shared responsibilities, avoidance of isolation, informal healthcare, and financial burdens are all reasons that result in larger households today; however, the current housing stock has not successfully responded to these emerging needs.

The thesis aims to re-think the current housing typology within the suburban fabric of Brampton to respond to its South Asian cultural demographic, develop better live-work, live-healthcare and live-education models that regulate land-use designations, and allow an increase in density and mixed-use programs. Given the importance of community involvement and a bottom-up approach in my own design philosophy, my primary methodology for research and design development involved working with three local organizations as part of a community engagement process to best understand the local needs. The following essay reflects on my experience with each organization, elaborating on shared conversations and findings that informed the design process that followed.

PEOPLE DESIGN CO-OP: CULTURAL PRACTICE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOUR

An architecture and planning firm located in Toronto, the People Design Co-op, engages in interviews with respective clients belonging to South Asian communities. Through informal conversations, the group unfolds the various ways these cultures inhabit space. By noting various lived experiences, the group provides the users with several tools to adapt and control the design of the spaces they would like to see. Given the work that this group had already done, I decided to reach out to them to learn about their findings. Our conversations revolved around how multi-generational families live, variable qualities of space, and levels of privacy families might need. These were complemented by topical discussions of togetherness, flexibility in design, expression of culture, and the importance of tradition in daily life.

These conversations allowed me to understand the relationship between the grandparents, their children, and the grandchildren living under the same roof, who exhibited a reciprocal relationship of knowledge, responsibilities, and care. Informal methods of healthcare are provided to seniors with the support of their family members. Similarly, children in the early stages of life do not require day care facilities, as the elders of the family take charge in caring for them as their parents go to work. This informs a mutual understanding of informal care that also extends beyond the boundaries of the family, integrating neighbors as another form of dependency when it comes to simpler tasks.

In these cases, the household sizes are naturally larger than usual, encompassing three generations. As such, future proofing is another important concept that guides the design of these spaces, allowing for flexibility, addition, and subtraction of spaces as the family size changes. Living in a large family often requires the creation of spaces for privacy, where one can experience some alone time, concentrating on work or tasks they intend to do. Types of privacy may also vary from visual to auditory, each requiring their own set of design guidelines. The organization of space also depends on the generation of people inhabiting it. For instance, younger individuals needed more space to move and play, in comparison to older generations who might have reduced mobility. In these cases, integrating accessibility and universal design for all age groups is often necessary.

On the other hand, there are many occasions that require a large communal space for all generations to convene: from family dinners and cooking meals, to entertaining guests. These activities target two main programs within a house: the living and the kitchen areas. Similarly, these communal spaces may be used during festivals and the performance of culturally significant rituals. These occasions may be celebrated at home and require larger space for gathering friends and family. Additionally, these events may have a sacred element attached to their design, which must be considered alongside their everyday uses. The design of outdoor space is particularly relevant during special occasions such as festivals: gathering, eating, dancing, and praying in the presence of larger crowds are all activities that must be accounted for. Overall, the People Design Co-op’s methods of informal interviewing provided useful in revealing underlying principles of aging, care, and cultural context. Much of this knowledge came in the form of personal anecdotes, not otherwise documented, and were only brought to surface through an intentional line of inquiry.

CITY OF BRAMPTON: SITE SELECTION, URBAN DESIGN, AND OPERATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

In selecting a site for my project, it was important for me to understand current and future sites of development, as well as the geography of the South Asian population around the Greater Toronto Area, with the majority residing in Brampton. Consequently, Mount Pleasant Village was selected as a proposed site. A relatively new neighborhood, Mount Pleasant Village is currently undergoing rapid growth, with new developments creating density around one of the regional GO train stations in the city. To better interpret the site and its possibilities, I initiated a conversation with the urban design team at the City of Brampton—a series of exchanges that broadened the scale of design to that of the neighborhood and its urban context.

Existing housing typologies, the total number of high-rise towers, and sprawls of single-family housing were all topics of discussion, with ideas for new housing situations tested on a single in order to replicate its societal benefits on a larger, typological scale. Diving into the history of the site, the designers highlighted the presence of the GO station—dating back to the 1990s—and development companies that first built housing around this node.

The discussion revealed the intended plans by the city to designate the area as a major transit-oriented development zone, increasing accessibility to public transit, reducing car use, and encouraging mixed-use typologies. While addressing future requirements of the neighborhood, a large number of retail, commercial and industrial programs were envisioned to increase the employment opportunities in the area. A special focus was paid to the design of the ground floor, as a means of engaging foot traffic, as well as creating live-work units, retail, entertainment, and commercial street fronts to uplift the urban character of the neighborhood.

There are several projects under construction near the chosen site. Diving further into each project allows one to observe how each is responding to the framework outlined by the city: from the proportion of public to private programs present, to the range of housing options provided to future residents. The overall massing height and density are also guided by the budget and surrounding commercial sites, as there are very few developments around the site. Much of the land, including my site, is bare at the moment. The proximity of these projects to my site will directly inform my design strategies, the number of floors, density and public programs that cohesively create a mix-use, multi-generational and multi-cultural form of housing project.

Several strategic plans targeting a future vision towards 2040 also revealed sustainability standards, including design of the public amenities, transit-friendly infrastructure, and extensive parks designed for humans, vegetation, animal, and bird species to thrive. Many passive and active design strategies form the framework for future proposals and an overall low-carbon master plan, including geoexchange, solar panels, net-zero materials, and efficient systems. Overall, engaging in dialogue with the City of Brampton’s urban design team enriched my contextual awareness and allowed me to develop a preliminary understanding of the future of my selected site. Following these learnings, my interventions will contribute towards a sustainable urban realm that resonates with the city’s expectations.

ARCANA RESTORATION GROUP: CIRCULAR MATERIAL EXPLORATIONS

Lastly, scaling down in design to explore material options, I encountered Arcana Restoration Group—a company working in heritage masonry and restoration. I had preliminarily intended to use brick as a material in the facade of my design to create a cultural connection between local typologies and South Asian construction; however, earlier conversation about sustainability led me to take this idea one step further. As a company that manages the re-use of brick material, my conversations with the Arcana Restoration Group allowed me to understand the potentials and economic benefits of material reuse.

Careful deconstruction practices reduce the amount of material that ends up in the landfill, instead allowing this material to be reclaimed towards a new purpose. The company shared that they acquire bricks from old farmhouses outside of the city, as costs and storage within the city becomes problematic. They also elaborated on the process of de-construction, cleaning and removal of the motor are integral for a new life for the material. Modern machinery has been developed to ease this process and make for a more unified production of secondary material. Regardless of its low popularity in the North American context, we discussed the potential of this method to become a readily accessible and economical option, as seen in the Netherlands.

CONCLUSION AND FURTHER APPLICATIONS

In reflecting on my interactions with each organization, each group addressed a group of design topics at a particular scale that I would later design: from the scale of building materials, to community needs, and broader urban considerations. Where accessing existing research about a community may provide a limited depth of information, community engagement and direct conversations can provide a more holistic view. My resulting thesis will aim to build upon these multi-layered findings, designing iteratively for a suburban fabric that is becoming increasingly multicultural and multi-generational.

I am currently in the final year of the Master of Architecture program at University of Toronto. I hold a Bachelor of Architectural Studies from McEwen School of Architecture, Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario. Originally, I grew up in Mumbai, India where most of my family still resides. After moving to Canada to pursue architectural education I have also explored my interests in traveling various countries, many of them in Europe and Scandinavian regions. I enjoy various forms of public projects, interactions and social conversations around design and our built environment. I am registered as a student associate with the Ontario Association of Architects and members with Toronto Society of Architects as well as Society of South Asian Architects in Canada.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Conceptual Diagram, Material Exploration, & Spatial Organization, 2023-2024. Muskan Goel.

How can culturally appropriate design respond to the growing needs for multigenerational living amongst the South Asian community in Brampton?

Multi-generational living is a traditional model where large households dwell under one roof and share knowledge and activities, such as cooking and dining. There are multiple reasons why this model of living might transpose itself into the existing Western home that characterizes our suburban landscape. Cultural practices, shared responsibilities, avoidance of isolation, informal healthcare, and financial burdens are all reasons that result in larger households today; however, the current housing stock has not successfully responded to these emerging needs.

The thesis aims to re-think the current housing typology within the suburban fabric of Brampton to respond to its South Asian cultural demographic, develop better live-work, live-healthcare and live-education models that regulate land-use designations, and allow an increase in density and mixed-use programs. Given the importance of community involvement and a bottom-up approach in my own design philosophy, my primary methodology for research and design development involved working with three local organizations as part of a community engagement process to best understand the local needs. The following essay reflects on my experience with each organization, elaborating on shared conversations and findings that informed the design process that followed.

PEOPLE DESIGN CO-OP: CULTURAL PRACTICE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOUR

An architecture and planning firm located in Toronto, the People Design Co-op, engages in interviews with respective clients belonging to South Asian communities. Through informal conversations, the group unfolds the various ways these cultures inhabit space. By noting various lived experiences, the group provides the users with several tools to adapt and control the design of the spaces they would like to see. Given the work that this group had already done, I decided to reach out to them to learn about their findings. Our conversations revolved around how multi-generational families live, variable qualities of space, and levels of privacy families might need. These were complemented by topical discussions of togetherness, flexibility in design, expression of culture, and the importance of tradition in daily life.

These conversations allowed me to understand the relationship between the grandparents, their children, and the grandchildren living under the same roof, who exhibited a reciprocal relationship of knowledge, responsibilities, and care. Informal methods of healthcare are provided to seniors with the support of their family members. Similarly, children in the early stages of life do not require day care facilities, as the elders of the family take charge in caring for them as their parents go to work. This informs a mutual understanding of informal care that also extends beyond the boundaries of the family, integrating neighbors as another form of dependency when it comes to simpler tasks.

In these cases, the household sizes are naturally larger than usual, encompassing three generations. As such, future proofing is another important concept that guides the design of these spaces, allowing for flexibility, addition, and subtraction of spaces as the family size changes. Living in a large family often requires the creation of spaces for privacy, where one can experience some alone time, concentrating on work or tasks they intend to do. Types of privacy may also vary from visual to auditory, each requiring their own set of design guidelines. The organization of space also depends on the generation of people inhabiting it. For instance, younger individuals needed more space to move and play, in comparison to older generations who might have reduced mobility. In these cases, integrating accessibility and universal design for all age groups is often necessary.

“Future proofing is another important concept that guides the design of these spaces, allowing for flexibility, addition, and subtraction of spaces as the family size changes.”

On the other hand, there are many occasions that require a large communal space for all generations to convene: from family dinners and cooking meals, to entertaining guests. These activities target two main programs within a house: the living and the kitchen areas. Similarly, these communal spaces may be used during festivals and the performance of culturally significant rituals. These occasions may be celebrated at home and require larger space for gathering friends and family. Additionally, these events may have a sacred element attached to their design, which must be considered alongside their everyday uses. The design of outdoor space is particularly relevant during special occasions such as festivals: gathering, eating, dancing, and praying in the presence of larger crowds are all activities that must be accounted for. Overall, the People Design Co-op’s methods of informal interviewing provided useful in revealing underlying principles of aging, care, and cultural context. Much of this knowledge came in the form of personal anecdotes, not otherwise documented, and were only brought to surface through an intentional line of inquiry.

CITY OF BRAMPTON: SITE SELECTION, URBAN DESIGN, AND OPERATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

In selecting a site for my project, it was important for me to understand current and future sites of development, as well as the geography of the South Asian population around the Greater Toronto Area, with the majority residing in Brampton. Consequently, Mount Pleasant Village was selected as a proposed site. A relatively new neighborhood, Mount Pleasant Village is currently undergoing rapid growth, with new developments creating density around one of the regional GO train stations in the city. To better interpret the site and its possibilities, I initiated a conversation with the urban design team at the City of Brampton—a series of exchanges that broadened the scale of design to that of the neighborhood and its urban context.

Existing housing typologies, the total number of high-rise towers, and sprawls of single-family housing were all topics of discussion, with ideas for new housing situations tested on a single in order to replicate its societal benefits on a larger, typological scale. Diving into the history of the site, the designers highlighted the presence of the GO station—dating back to the 1990s—and development companies that first built housing around this node.

The discussion revealed the intended plans by the city to designate the area as a major transit-oriented development zone, increasing accessibility to public transit, reducing car use, and encouraging mixed-use typologies. While addressing future requirements of the neighborhood, a large number of retail, commercial and industrial programs were envisioned to increase the employment opportunities in the area. A special focus was paid to the design of the ground floor, as a means of engaging foot traffic, as well as creating live-work units, retail, entertainment, and commercial street fronts to uplift the urban character of the neighborhood.

“Diving further into each project allows one to observe how each is responding to the framework outlined by the city: from the proportion of public to private programs present, to the range of housing options provided to future residents.”

There are several projects under construction near the chosen site. Diving further into each project allows one to observe how each is responding to the framework outlined by the city: from the proportion of public to private programs present, to the range of housing options provided to future residents. The overall massing height and density are also guided by the budget and surrounding commercial sites, as there are very few developments around the site. Much of the land, including my site, is bare at the moment. The proximity of these projects to my site will directly inform my design strategies, the number of floors, density and public programs that cohesively create a mix-use, multi-generational and multi-cultural form of housing project.

Several strategic plans targeting a future vision towards 2040 also revealed sustainability standards, including design of the public amenities, transit-friendly infrastructure, and extensive parks designed for humans, vegetation, animal, and bird species to thrive. Many passive and active design strategies form the framework for future proposals and an overall low-carbon master plan, including geoexchange, solar panels, net-zero materials, and efficient systems. Overall, engaging in dialogue with the City of Brampton’s urban design team enriched my contextual awareness and allowed me to develop a preliminary understanding of the future of my selected site. Following these learnings, my interventions will contribute towards a sustainable urban realm that resonates with the city’s expectations.

ARCANA RESTORATION GROUP: CIRCULAR MATERIAL EXPLORATIONS

Lastly, scaling down in design to explore material options, I encountered Arcana Restoration Group—a company working in heritage masonry and restoration. I had preliminarily intended to use brick as a material in the facade of my design to create a cultural connection between local typologies and South Asian construction; however, earlier conversation about sustainability led me to take this idea one step further. As a company that manages the re-use of brick material, my conversations with the Arcana Restoration Group allowed me to understand the potentials and economic benefits of material reuse.

Careful deconstruction practices reduce the amount of material that ends up in the landfill, instead allowing this material to be reclaimed towards a new purpose. The company shared that they acquire bricks from old farmhouses outside of the city, as costs and storage within the city becomes problematic. They also elaborated on the process of de-construction, cleaning and removal of the motor are integral for a new life for the material. Modern machinery has been developed to ease this process and make for a more unified production of secondary material. Regardless of its low popularity in the North American context, we discussed the potential of this method to become a readily accessible and economical option, as seen in the Netherlands.

CONCLUSION AND FURTHER APPLICATIONS

In reflecting on my interactions with each organization, each group addressed a group of design topics at a particular scale that I would later design: from the scale of building materials, to community needs, and broader urban considerations. Where accessing existing research about a community may provide a limited depth of information, community engagement and direct conversations can provide a more holistic view. My resulting thesis will aim to build upon these multi-layered findings, designing iteratively for a suburban fabric that is becoming increasingly multicultural and multi-generational.