In Conversation with Yeo-Jin Katerina Bong

BIOGRAPHY

Yeo-Jin Katerina Bong is an architectural historian with a special interest in building technology, infrastructure, engineering, and architectural manuals of early-modern Italy. Coming from a family of engineers, their father studied civil engineering and their grandfather worked as a construction manager building dams, bridges, and highways in South Korea. Unconsciously, this background slipped into their research, which melded with their studies in art and architectural history.

As a historian of the built environment, Bong is fascinated by the impulse towards sturdy buildings, stable cities, and a robust society (specifically the aversion towards failure, collapses, and defects) which functioned as a common driver for many civilizations across geographical and temporal scales. Many of these building knowledges were passed down as building manuals which recorded and illustrated building procedures, materials, and techniques. Bong’s doctoral dissertation examines building manuals in general, and European and Asian architectural knowledge in particular, to insert artisanal, practical, and infrastructural knowledge as key tools of methodological inquiry in the study of the built environment.

Yeo-Jin Katerina Bong is an architectural historian with a special interest in building technology, infrastructure, engineering, and architectural manuals of early-modern Italy. Coming from a family of engineers, their father studied civil engineering and their grandfather worked as a construction manager building dams, bridges, and highways in South Korea. Unconsciously, this background slipped into their research, which melded with their studies in art and architectural history.

As a historian of the built environment, Bong is fascinated by the impulse towards sturdy buildings, stable cities, and a robust society (specifically the aversion towards failure, collapses, and defects) which functioned as a common driver for many civilizations across geographical and temporal scales. Many of these building knowledges were passed down as building manuals which recorded and illustrated building procedures, materials, and techniques. Bong’s doctoral dissertation examines building manuals in general, and European and Asian architectural knowledge in particular, to insert artisanal, practical, and infrastructural knowledge as key tools of methodological inquiry in the study of the built environment.

Facilitated by the Scaffold* Editorial Team in February 2024.

Read the article in PDF form here.

![]()

![]()

Figure 1. Namdaemun After Fire, Seoul, South Korea, 2008. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. Firefighter At Namdaemun, Seoul, South Korea, 2008. Wikimedia Commons.

Q: Can you briefly describe the breadth of your research interests and work?

I mostly deal with Italian Renaissance architecture. I utilize contemporary perspectives to analyze the history of architecture. In particular, I utilize the notion of failure and structural collapse, and how that was interpreted and understood at that point in the Renaissance, because it probably had a different connotation then, than it does to us right now. And I kind of look at two different perspectives: the cultural significance of what it meant for buildings to collapse and the structural components of how the architects at that point dealt with structural failures. I’m interested in the way that building design and graphics were being used on the construction side.

Q: Has there been a key monument or structure that has changed the course of your research?

You could say that my interests began with the Leaning Tower of Pisa. It’s generally known as a very touristy site (where people go take photos in really weird manners). I was extremely interested in why the Tower wasn’t more seriously investigated in a more scholarly manner, so I started digging into the archival materials. I noticed that when they started building the Tower of Pisa in 1127, they already knew that it was starting to tilt, but they didn’t actually do anything to deal with it. By the time they went all the way up to the upper stories they added additional stones on the leaning side of the tower, so it would optically reduce the tilting.

In the 16th century, an author named Giorgio Vasari documented the tilting tower, claiming that it was a miracle. So really, there were two interpretations for Pisa: a cultural, or even religious, based interpretation, and then the structural. This is one of the main reasons why I wanted to investigate the structural aspect: usually, when people think of Renaissance architecture, it’s conceived as pristine and perfect—made from the hands of God. But if you really look into it, a lot of the buildings from this era weren’t as perfect as we thought they were.

Beyond Renaissance architecture, I also write about East Asian monuments. I recently wrote about the Sungnyemun—a 14th-century Korean building that caught on fire and was completely destroyed. The cultural responses that were elicited from that particular building’s collapse are really illustrative of the phenomenological aspect that I’m interested in investigating, above the structural and mechanical side of failure.

![]()

Figure 3. Bridge Observation at Ponte Ameilius, Rome, Italy. Yeo-Jin Katerina Bong.

Q: What does the process behind your research look like? What are some key tools that you work with in your research?

I conduct a substantial amount of archival research. As a fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, I have access to their archives, which are basically shelves and shelves of different materials. A key issue with archival research is that you might not know where things are. You know that it exists, but you actually have to dig into TMS or a paper catalogue in order to find the particular resources that you need.

Going more in depth, I look at different graphics and images very closely. I examine what the document or object actually says as well as types of numbering. It’s critical to ask questions about the state of the object. Why is this particular folio upside down? How was it broken down? What is this particular building saying and where is this building from? In the context of museum-based research, curatorial notes can be extremely helpful. In short, a lot of the process involves digging into the specific notes of the curators, or even the archivist and trying to utilize this as a springboard to take me into the next steps of my research.

Like many scholars, my research extends beyond the archives. On-site research is critical to understanding this site’s situation. While in Rome, I started noticing that certain bridges were broken down while others were intact. I took photos of different structures on-site and completed a comparative analysis with images or graphics that existed from the 16th and 17th centuries. This allowed me to see what the bridge might have looked like, and what sort of discussions they were having about bridges at that point. These are two key ways that scholars in my field, from the early modern period, tend to tackle these sorts of materials.

![]()

![]()

Figure 4. An image from the Ben Cao Gang Mu (Compendium of Materia Medica), China, 1603. Jiangxi Sheng.

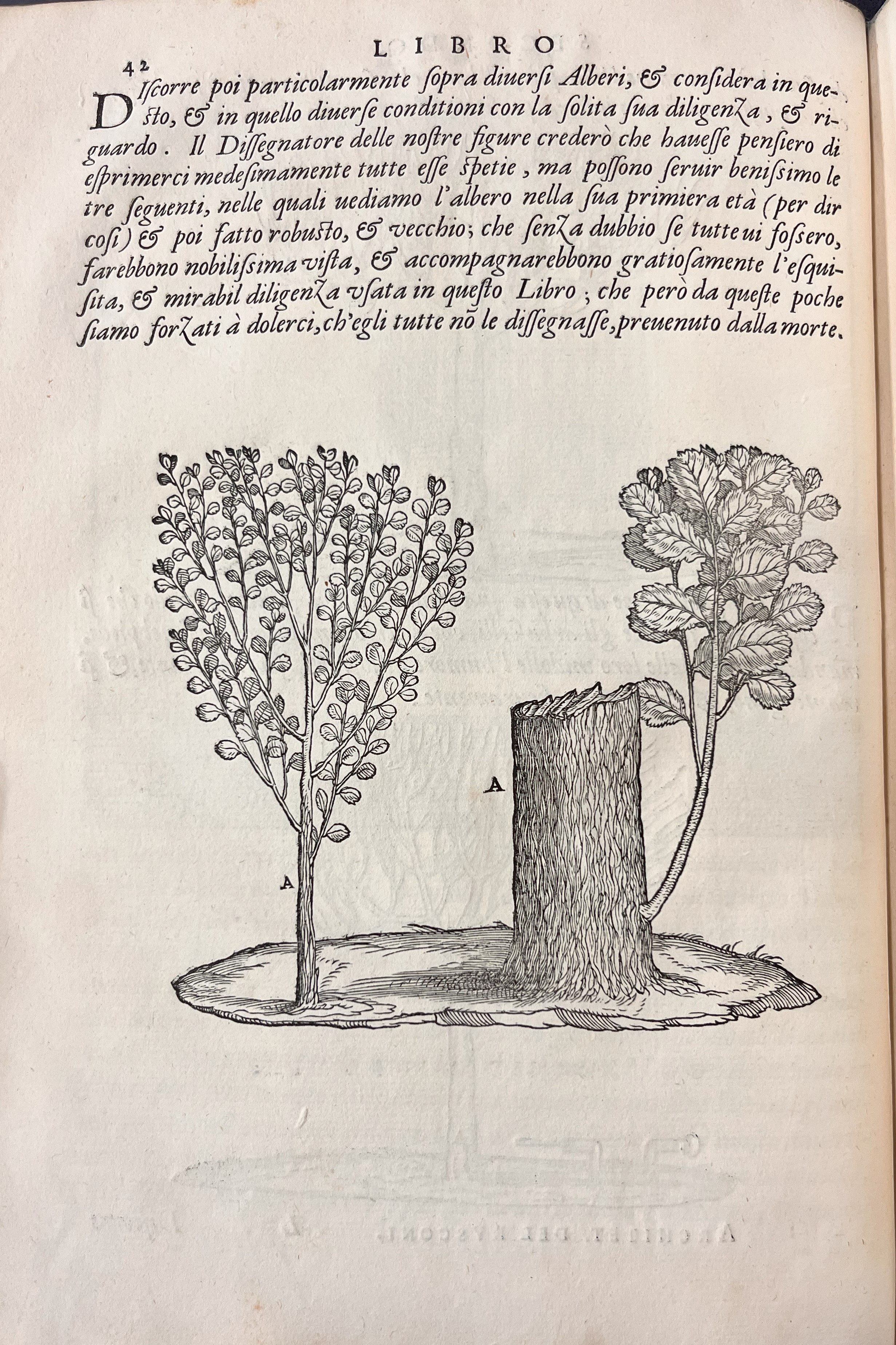

Figure 5. Tree illustration, 1669. Giovanni Antonio Rusconi.

Q: Do you utilize any methods that might be considered unconventional in the realms of art and architectural history?

Just trying to get a feel of how people are interacting with the site is immensely important. For many historical works, which have been in the same place for ages, the way that humans or people interact with the particular site doesn’t necessarily change. So for me, a lot of the work goes into trying to utilize our contemporary senses in order to understand the historical past. This could be considered somewhat unconventional, as a lot of scholars may say that this is anachronistic or an application of our modern perspectives to the past.

We have many different ways of interacting with sites, whether it be tactile, how we see it or even how we smell it. I have a sense that it doesn’t really change as much. Take, for instance, a historical bridge. There may still be a river with running water and people crossing and going around the bridge. A lot of my method is based upon thinking about how people at that point might have utilized that particular structure, and thinking about how I can utilize my current position to access this perspective.

Q: You study both Early European Modernism and East Asian Architecture. Have you always studied both concurrently? Do you ever bridge these areas of research together, and if so, what does this look like?

For me, studying early modern architecture as a female Korean is not easy. Coming from the lens of a Korean individual, I always felt that there was a universality in architecture. An example that I really love comes from a European 15th century design of a column, designed in the image of a tree. When you compare this representation to a particular temple from Korea, you can observe a similar natural curvature. I’m interested in looking at how people from different cultures approached the column as not only a structural device, but also something that comes out from nature.

Building upon this, I often use trees, wood, and timber as a framework to compare the two cultures. When I was a child, I lived in the mountainous regions of Korea, which often had many temples. The more I go back now, I’ve started seeing these temples and palaces with my knowledge of European architecture, and making connections between them. One key connection can be seen through how trees were documented in both cultures. There’s this shared human impulse to categorize everything about trees and their uses. This includes the particular times in the year that are best for trees to be felled, or what sort of tree species are to be used for a particular building, but can also be about how different species can be utilized for herbal medicine and other human uses.

![]()

Figure 6. Cheongnyongsa Temple, Chuncheon, South Korea.

Q: Regarding the broader discourse of your research, what do you hope that your work surrounding failed buildings and their cultural responses contributes to? What are you currently working on and what’s next?

My current dissertation looks at how foundational issues were historically dealt with. For instance, St. Peter’s Basilica has historically had many structural deficiencies, from cracks to structural unevenness in the floor. In the 16th and 17th centuries, people started realizing that the building was actually sinking into the ground, with cracks appearing on the sides of the walls. They utilized graphics in order to understand what was happening underground. People actually dug under St. Peter’s Basilica to try to figure out ways to reinforce its building structure. This is one way that I’m interested in studying the problem—looking at the hidden underground as a way to understand a building.

I’m really interested in thinking about different ways of looking at buildings—especially from the history of engineering and science. Anyone who has taken Renaissance architectural history, or who has studied the history of architecture components, has encountered discussions about rationalism or proportion. I’m less interested in that and more interested in how particular buildings come about. One way of studying this is through building structures. In short, my contributions to the field aims to expand its methodological horizons. I’m not trying to discard discussions of rationalism, but through my work, I’m attempting to show that there are other ways and angles to look at buildings.

Read the article in PDF form here.

Figure 1. Namdaemun After Fire, Seoul, South Korea, 2008. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. Firefighter At Namdaemun, Seoul, South Korea, 2008. Wikimedia Commons.

Q: Can you briefly describe the breadth of your research interests and work?

I mostly deal with Italian Renaissance architecture. I utilize contemporary perspectives to analyze the history of architecture. In particular, I utilize the notion of failure and structural collapse, and how that was interpreted and understood at that point in the Renaissance, because it probably had a different connotation then, than it does to us right now. And I kind of look at two different perspectives: the cultural significance of what it meant for buildings to collapse and the structural components of how the architects at that point dealt with structural failures. I’m interested in the way that building design and graphics were being used on the construction side.

Q: Has there been a key monument or structure that has changed the course of your research?

You could say that my interests began with the Leaning Tower of Pisa. It’s generally known as a very touristy site (where people go take photos in really weird manners). I was extremely interested in why the Tower wasn’t more seriously investigated in a more scholarly manner, so I started digging into the archival materials. I noticed that when they started building the Tower of Pisa in 1127, they already knew that it was starting to tilt, but they didn’t actually do anything to deal with it. By the time they went all the way up to the upper stories they added additional stones on the leaning side of the tower, so it would optically reduce the tilting.

“When people think of Renaissance architecture, it’s conceived as pristine and perfect—made from the hands of God. But if you really look into it, a lot of the buildings from this era weren’t as perfect as we thought they were.”

In the 16th century, an author named Giorgio Vasari documented the tilting tower, claiming that it was a miracle. So really, there were two interpretations for Pisa: a cultural, or even religious, based interpretation, and then the structural. This is one of the main reasons why I wanted to investigate the structural aspect: usually, when people think of Renaissance architecture, it’s conceived as pristine and perfect—made from the hands of God. But if you really look into it, a lot of the buildings from this era weren’t as perfect as we thought they were.

Beyond Renaissance architecture, I also write about East Asian monuments. I recently wrote about the Sungnyemun—a 14th-century Korean building that caught on fire and was completely destroyed. The cultural responses that were elicited from that particular building’s collapse are really illustrative of the phenomenological aspect that I’m interested in investigating, above the structural and mechanical side of failure.

Figure 3. Bridge Observation at Ponte Ameilius, Rome, Italy. Yeo-Jin Katerina Bong.

Q: What does the process behind your research look like? What are some key tools that you work with in your research?

I conduct a substantial amount of archival research. As a fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, I have access to their archives, which are basically shelves and shelves of different materials. A key issue with archival research is that you might not know where things are. You know that it exists, but you actually have to dig into TMS or a paper catalogue in order to find the particular resources that you need.

Going more in depth, I look at different graphics and images very closely. I examine what the document or object actually says as well as types of numbering. It’s critical to ask questions about the state of the object. Why is this particular folio upside down? How was it broken down? What is this particular building saying and where is this building from? In the context of museum-based research, curatorial notes can be extremely helpful. In short, a lot of the process involves digging into the specific notes of the curators, or even the archivist and trying to utilize this as a springboard to take me into the next steps of my research.

“A key issue with archival research is that you might not know where things are. You know that it exists, but you actually have to dig...in order to find the particular resources that you need.”

Like many scholars, my research extends beyond the archives. On-site research is critical to understanding this site’s situation. While in Rome, I started noticing that certain bridges were broken down while others were intact. I took photos of different structures on-site and completed a comparative analysis with images or graphics that existed from the 16th and 17th centuries. This allowed me to see what the bridge might have looked like, and what sort of discussions they were having about bridges at that point. These are two key ways that scholars in my field, from the early modern period, tend to tackle these sorts of materials.

Figure 4. An image from the Ben Cao Gang Mu (Compendium of Materia Medica), China, 1603. Jiangxi Sheng.

Figure 5. Tree illustration, 1669. Giovanni Antonio Rusconi.

Q: Do you utilize any methods that might be considered unconventional in the realms of art and architectural history?

Just trying to get a feel of how people are interacting with the site is immensely important. For many historical works, which have been in the same place for ages, the way that humans or people interact with the particular site doesn’t necessarily change. So for me, a lot of the work goes into trying to utilize our contemporary senses in order to understand the historical past. This could be considered somewhat unconventional, as a lot of scholars may say that this is anachronistic or an application of our modern perspectives to the past.

“...a lot of the work goes into trying to utilize our contemporary senses in order to understand the historical past.”

We have many different ways of interacting with sites, whether it be tactile, how we see it or even how we smell it. I have a sense that it doesn’t really change as much. Take, for instance, a historical bridge. There may still be a river with running water and people crossing and going around the bridge. A lot of my method is based upon thinking about how people at that point might have utilized that particular structure, and thinking about how I can utilize my current position to access this perspective.

Q: You study both Early European Modernism and East Asian Architecture. Have you always studied both concurrently? Do you ever bridge these areas of research together, and if so, what does this look like?

For me, studying early modern architecture as a female Korean is not easy. Coming from the lens of a Korean individual, I always felt that there was a universality in architecture. An example that I really love comes from a European 15th century design of a column, designed in the image of a tree. When you compare this representation to a particular temple from Korea, you can observe a similar natural curvature. I’m interested in looking at how people from different cultures approached the column as not only a structural device, but also something that comes out from nature.

Building upon this, I often use trees, wood, and timber as a framework to compare the two cultures. When I was a child, I lived in the mountainous regions of Korea, which often had many temples. The more I go back now, I’ve started seeing these temples and palaces with my knowledge of European architecture, and making connections between them. One key connection can be seen through how trees were documented in both cultures. There’s this shared human impulse to categorize everything about trees and their uses. This includes the particular times in the year that are best for trees to be felled, or what sort of tree species are to be used for a particular building, but can also be about how different species can be utilized for herbal medicine and other human uses.

Figure 6. Cheongnyongsa Temple, Chuncheon, South Korea.

Q: Regarding the broader discourse of your research, what do you hope that your work surrounding failed buildings and their cultural responses contributes to? What are you currently working on and what’s next?

My current dissertation looks at how foundational issues were historically dealt with. For instance, St. Peter’s Basilica has historically had many structural deficiencies, from cracks to structural unevenness in the floor. In the 16th and 17th centuries, people started realizing that the building was actually sinking into the ground, with cracks appearing on the sides of the walls. They utilized graphics in order to understand what was happening underground. People actually dug under St. Peter’s Basilica to try to figure out ways to reinforce its building structure. This is one way that I’m interested in studying the problem—looking at the hidden underground as a way to understand a building.

“I’m not trying to discard discussions of rationalism, but through my work, I’m attempting to show that there are other ways and angles to look at buildings.”

I’m really interested in thinking about different ways of looking at buildings—especially from the history of engineering and science. Anyone who has taken Renaissance architectural history, or who has studied the history of architecture components, has encountered discussions about rationalism or proportion. I’m less interested in that and more interested in how particular buildings come about. One way of studying this is through building structures. In short, my contributions to the field aims to expand its methodological horizons. I’m not trying to discard discussions of rationalism, but through my work, I’m attempting to show that there are other ways and angles to look at buildings.